Presidential Elections in Chad

In many ways, Chad has come a long way since the last presidential election held in 2006. Back then, President Deby’s decision to change the constitution to allow him to stand for a third term poured fuel onto the flames of a rebellion already burning in the east. Egged on by Sudanese arms and support, these rebels crossed a thousand kilometres of desert in a few days and attacked the capital N’Djamena just weeks before the election was held. Two years later, and with a new acronym and a variation in members and leadership, the rebels were back and came within moments of unseating Deby. The resulting crackdown on anyone believed to be involved in the rebellion poisoned the political scene in Chad and caused legislative elections to be postponed several times.

But those elections did take place in February 2011, and although there was widespread criticism of the electoral body the CENI, it remains significant that they, and March’s presidential election, took place in a period of relative stability.

The reason for this dramatic improvement in security seems in large part due to last year’s rapprochement between Chad and Sudan, who had become bitter and twisted enemies through a proxy war which lasted from 2004 to 2009. President Omar el-Bashir felt that Deby had not done enough to deal with elements of the Darfur rebels who had rear bases in the east of Chad; in return Deby was incensed by Bashir’s sponsorship of the UFDD and the subsequent UFR. But Chad and Sudan surprised some by dealing with their problems in their own time, forcing the UN peacekeeping mission Minurcat which was supposed to restore stability to Chad’s volatile east to leave in 2010, and replacing it with a their own joint border force.

What hasn’t improved in that time is Chad’s domestic political scene. As in 2006, a number of opposition figures boycotted this year’s presidential poll, citing what they called terminal failures with the CENI. Some Chadians had pinned their hopes on Ngarley Yorongar, Saleh Kebzabo and Wadal Kamogue as the only political heavyweights capable of giving Deby a run for his money; and while the trios’ concerns were real enough (Kebzabo found a number of pre-printed voters’ cards on sale in N’Djamena’s main market), their withdrawal from the race left voters with a less than satisfying choice. Padack Pahimi Albert has served on several occasions as a minister in Deby’s government, and Nadji Madou is a vibrant young lawyer with little political experience.

The opposition were also seemingly unable to unite for the legislative elections, where the CPDC (Coalition for the Protection of the Constitution) was unable to prevent around 100 different opposition parties standing. In some parts of the south, Deby’s ruling MPS party did not gain a majority of the vote, but the splitting of the opposition meant they took the seats anyway. Deby retains strong control of the National Assembly with 131 out of 188 seats.

The legitimacy of Deby’s new term to some extent rests on the voter turn-out on Monday, which was low. His assertion that the opposition did not stand “because they knew they would lose” will never be tested, but he will argue he has a strong mandate to continue with his “˜renaissance’ programme of building roads, hospitals and schools using oil revenues.

However many Chadians still live in dire poverty, with poor electricity provision, running water or basic services. It’s impossible to rule out the kind of protests seen in other African countries against rising food and fuel costs, but real momentum for change will need to come from a new generation of younger opposition leaders who are more in touch with the feelings of people on the streets.

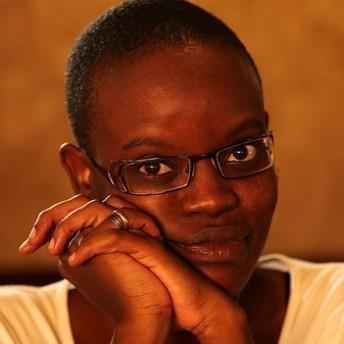

By Celeste Hicks, BBC World Service