Malawi: Bingu turns apocalyptic – By Nick Wright

By the peaceful standards of modern Malawi, the 20th of July was a very bloody day indeed. At least 19 people were killed and many more were injured, in demonstrations against the Mutharika government that took place in and around the main cities of Lilongwe, Blantyre, Zomba and Mzuzu. Having begun in a peaceful, carnival, atmosphere of red shirts and banners, they quickly turned violent as the heavily-armed police and army, finding themselves in a period of indecision over the legality of these protests, responded characteristically with live bullets and tear-gas.

By the peaceful standards of modern Malawi, the 20th of July was a very bloody day indeed. At least 19 people were killed and many more were injured, in demonstrations against the Mutharika government that took place in and around the main cities of Lilongwe, Blantyre, Zomba and Mzuzu. Having begun in a peaceful, carnival, atmosphere of red shirts and banners, they quickly turned violent as the heavily-armed police and army, finding themselves in a period of indecision over the legality of these protests, responded characteristically with live bullets and tear-gas.

The old men who lead the Malawian Opposition parties, John Tembo for the Malawi Congress Party, and Friday Jumbe for the United Democratic Front, quickly melted away from the angry streets, leaving the escalating riots to a a few hard-pressed protest marshals and the party-youth of the governing, Democratic Progressive Party. As always, there were large numbers of angry young men, freed by Malawi’s huge unemployment crisis and eager to express their multitude dissatisfactions.

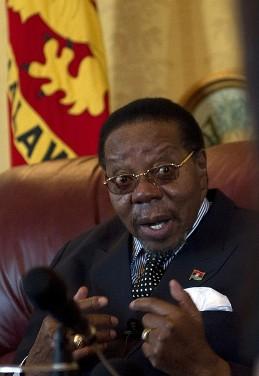

President Bingu wa Mutharika, himself a nervous and irascible old man, now ruefully contemplates the burned-out houses and the looted shops of this “Warm Heart of Africa” and he blames western interference, along with “satanic” local Civil Society groupings, for the disaster. His rhetoric is becoming increasingly incoherent and apocalyptic.

Bingu’s massive first-term (2004-2009) popularity on the domestic and international fronts, now seems very distant. It was based on his decision to channel Malawi’s scarce foreign exchange reserves into the purchase of foreign chemical fertilisers and hybrid seeds for subsidised use by Malawi’s millions of smallholder, maize-growing, farmers. That bold presidential decision propelled Malawi from regular food deficits to a permanent over-production of the maize food staple. It made Bingu — who was only copying what the USA and the EU had been doing for decades — into an overnight expert on food security and, for many Malawians, their very own “economic engineer”. Even the bilateral and multilateral aid agencies which have kept the Malawian economy unsteadily on its feet since Independence in 1964 and have been temperamentally suspicious of such “unsustainable” economic strategies, were prepared to contribute regularly, through “Budget Support”, to this subsidy, on the principle that emergency food-aid is even more unpredictable and costly.

Bingu, however, lacks political subtlety. He has managed simultaneously to alienate Malawi’s two main generators of foreign exchange: the international donors and the international tobacco-buyers. However understandable it may be, his very public hostility towards their representatives in Malawi: the diplomats of the western embassies in Lilongwe and the American executives of the tobacco-buying companies, Alliance One and Limbe Leaf, has been nothing short of reckless. It has shaken even the British government’s unwavering attachment to its swollen Department for International Development in Malawi. Other bilateral and multilateral agencies are taking their cue from Britain by withholding aid. Furthermore, the market for Malawi’s export staple, burley tobacco, already in serious decline, is more than a little impatient with Bingu’s futile attempts to set minimum prices on the auction floors and interfere in personnel management.

These anxieties and uncertainties have fed into the July 20 riots through the recent austerity budget of Finance Minister Ken Kandodo. Urban Malawians, who gave Bingu and his DPP-party a landslide majority in 2009, and called him the Modern Moses, now blame him for every long queue outside petrol-filling stations, every price–rise in the shops, every interruption in electricity-supply and water-supply, every time foreign exchange is unavailable in the banks, every tax-rise. Such things are becoming daily more frequent. Because of Bingu’s public face as a finger-waggng All-Wise and All-Knowing Leader, he now must personally accept the major responsibility.

Nick Wright has worked in the History Department at Adelaide University (1975-1991) and for Africa Confidential as its Malawi correspondent (2003-2010).

Tembo did not choose to miss the protests, but was served with an injunction the day before forbidding him to participate.

http://habanahaba.wordpress.com/2011/07/20/a-day-of-protests-in-malawi-a-chronological-account-from-afar/

Thanks for the useful information, Daniel. Tembo’s injunction is a very good example of what the demonstrations were all about. The new injunctions legislation in Malawi favours government only, and prevents individuals from exercising their constitutional rights.