South Sudan’s Tryst with Destiny

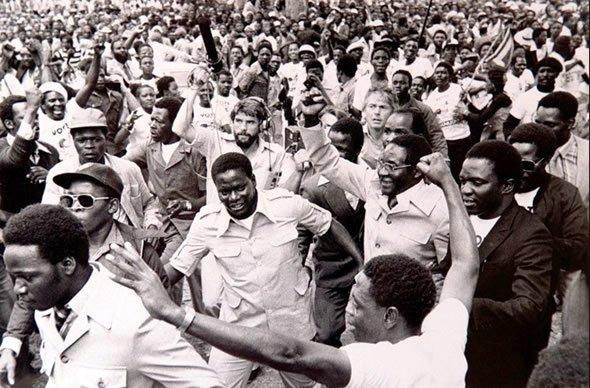

From the ashes of war, pestilence, and destruction has arisen a phoenix of a nation – the Republic of South Sudan, the 193rd member of the United Nations. May it prosper and grow into a model state rooted in peace, tolerance and freedom. As I listened to President Salva Kiir Mayardit’s eloquent oration on July 9, I was reminded of another historic oration, delivered some three score and four years ago… Considered to be one of the greatest speeches of all time, Jawaharlal Nehru’s landmark oration, “˜Tryst with Destiny’ captured the essence of the triumphant culmination of the hundred-year non-violent freedom struggle against the British Empire in India. Salva Kiir’s speech recounted the more than half a century of violent struggle that led to South Sudan’s independence, honouring the 2 million who laid down their lives to throw off the yoke of tyranny and injustice.

From the ashes of war, pestilence, and destruction has arisen a phoenix of a nation – the Republic of South Sudan, the 193rd member of the United Nations. May it prosper and grow into a model state rooted in peace, tolerance and freedom. As I listened to President Salva Kiir Mayardit’s eloquent oration on July 9, I was reminded of another historic oration, delivered some three score and four years ago… Considered to be one of the greatest speeches of all time, Jawaharlal Nehru’s landmark oration, “˜Tryst with Destiny’ captured the essence of the triumphant culmination of the hundred-year non-violent freedom struggle against the British Empire in India. Salva Kiir’s speech recounted the more than half a century of violent struggle that led to South Sudan’s independence, honouring the 2 million who laid down their lives to throw off the yoke of tyranny and injustice.

Both Jawaharlal Nehru and Salva Kiir delivered their speeches in English, an alien tongue incomprehensible to more than 99 percent of their fellow citizens; in both instances, the assembled masses across their new nations listened to the orations with reverence and rapt attention. Freedom transcends all barriers, even barriers of language and communication. But millions of Indians that were listening to the great man did not know what identity they would have the next day , especially those living close to the yet undefined border between the two new British dominions.

Likewise, the million or more Southern Sudanese left in the North and along an undefined north -south border must be wondering about their fate after listening to their leader in South Sudan.

The division of Sudan in 2011, given its vast panorama of ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity, has some similarities with the division of India in 1947. The land area and population of South Sudan -compared to the undivided Sudan, has a similar ratio to that of Pakistan (of 1947) compared to the undivided British India. The unresolved issues between the successor states are also similar – lack of a fully demarcated border, a disputed region (Kashmir vs. Abyei, each with its UN monitoring mission), undetermined rights of citizenship, abode, and travel of nationals of one country remaining voluntarily or stranded in the other country, unresolved division of assets (including the pensions and benefits of Southern Sudanese civil servants and soldiers who had served in undivided Sudan), and so on.

Moreover, the successor states are armed to the teeth, ready to go into battle at any provocation. On the human development front, the indicators for South Sudan – especially literacy and health outcomes – are not too far from those of 1947 Pakistan. At the political level, the National Congress Party of Sudan bears the primary responsibility for the vivisection of Sudan, just as historical evidence is beginning to reveal that the Indian Congress Party arguably had a bigger responsibility in the division of the Indian Sub-Continent. Pakistan’s Jinnah and South Sudan’s Garang were proponents of unity, and considered secession as a measure of last resort, when their demand for equal and fair representation within a federal structure was thwarted by the majority party.

Despite the vision charted by Nehru in his “˜Tryst with Destiny’, the division of India was followed by mayhem of unprecedented proportions: displacement of 10 million people, a million dead, ethnic cleansing, and a hot war over Kashmir. The aftermath of those events has reverberated over the subsequent six and a half decades; peace and coexistence between the successor states remain a distant prospect. South Sudan must ward against such an outcome.

What can South Sudan do to avert a future that might resemble the outcomes in the Indian Sub-Continent?

South Sudan today is faced with risks to its sovereignty and well-being similar to those faced by Pakistan in 1947. But there are lessons from Pakistan’s troubled and unstable history that have a lot of relevance for South Sudan. The first and foremost lesson is that a nation’s strength does not derive from its military size and prowess, but stems from its economic strength. South Sudan will do well to rein in the powers of SPLA and make it fully accountable to a democratically-elected civilian leadership. Independence of judiciary should remain an unshakable pillar of the country’s constitution, civilian law enforcement strengthened, and the military’s role confined to countenance external threats.

Secondly, South Sudan must respect and fully accommodate its ethnic and cultural diversity, make federalism and devolution of administrative and legislative powers to states, counties, bomas, payams, and villages as the cornerstone of governance, and ensure that the bulk of oil revenues is distributed equitably and fairly, by law, among the various levels of government and jurisdictions to avoid a sense of relative deprivation. The growing regional disparities (especially the economic prosperity in Juba relative to the rest of the country) need to be addressed urgently to forestall any secessionist tendencies.

Thirdly, the refugees from the North must be fully integrated into the South Sudanese mainstream, compensated for losses suffered, treated with equality and respect, and not allowed to become a disgruntled underclass in their own homeland. They bring a lot of talent and skills that South Sudan needs desperately.

Fourthly, it must focus all its energies on internal security, human development, social protection, and basic infrastructure (particularly roads) to create a geographically integrated and governable country. Fifthly, it must not deny its past and its common culture, history, and language with its northern neighbour – it is only shades of black that differentiate the various nationalities of Sudan – branding all northern Sudanese as Arabs is like calling all Brazilians, Portuguese, and all Spanish-speaking Latin Americans, Spanish, or for that matter calling all South Sudanese, Christians.

There is no greater denial of identity than the denial of history. Maintaining Arabic as a second language will not diminish South Sudan’s secular status but will provide it unrivalled access to the Arab world stretching from Morocco to Oman. Lastly, South Sudan must avoid becoming a pawn in global ideological rivalries and retain good and amicable relations with all its neighbours and its distant benefactors.

Had Pakistan adopted a similar agenda soon after its creation, it just might have avoided its current predicament.

By Asif Faiz

Consultant/Adviser; served as World Bank’s Country Manager for Sudan in Khartoum ( 2005-2008).

great site, i’m from South Sudan. intrested in your items