Two Deaths in Zimbabwe – by Timothy Scarnecchia

Two deaths in Zimbabwe’s political landscape happened a week apart in August. First came the tragic news of the murder of MDC-T politician Maxwell Ncube, whose body, according to VOA Zimbabwe, “was found August 9 in a ditch a few hundred yards from his homestead, wrapped in a sack, his head bearing the trauma of what appeared to be a blow from an axe.” Ncube had been attacked and beaten during the 2008 elections and his supporters, according to the MDC, believe ZANU-PF militants are behind his murder. The Solidarity Peace Trust’s April 2011 report, “The Hard Road to Reform” highlights the pervasiveness of such violence, with 190 cases of political violence reported in the first three months of this year.

The news of Ncube’s dea th was quickly overshadowed, however, by the death of a liberation war hero, Solomon Mujuru (nom de guerre Rex Nhongo), who died August 15th in a fire in his farmhouse in Beatrice, outside the capital of Harare. Mujuru’s wife, Joice Mujuru, is one of Zimbabwe’s two Vice Presidents. She and her husband were considered leaders of one of the main two factions fighting to take over ZANU-PF. As Andrew Meldrum reported, her husband’s death by fire led immediately to speculation of foul play. Wilf Mbanga, editor of the Zimbabwean, suggested that retired Zimbabwe National Army leader Mujuru had a history of falling asleep with the kettle on. Others blamed the frequent power outages. In any event, when the fire brigade arrived, they had brought no water with them. The Mujurus and others are now calling for investigations into General Solomon Mujuru’s death, even calling for outside help with the investigation. It will be very unlikely that the same careful attention to justice and truth finding will be afforded Maxwell Ncube’s family. He was buried in his home village of Ntenezi in Zhombe district, without the fanfare of a national hero’s burial. It is also unlikely that Mujuru’s death will be carefully investigated, but for different reasons.

th was quickly overshadowed, however, by the death of a liberation war hero, Solomon Mujuru (nom de guerre Rex Nhongo), who died August 15th in a fire in his farmhouse in Beatrice, outside the capital of Harare. Mujuru’s wife, Joice Mujuru, is one of Zimbabwe’s two Vice Presidents. She and her husband were considered leaders of one of the main two factions fighting to take over ZANU-PF. As Andrew Meldrum reported, her husband’s death by fire led immediately to speculation of foul play. Wilf Mbanga, editor of the Zimbabwean, suggested that retired Zimbabwe National Army leader Mujuru had a history of falling asleep with the kettle on. Others blamed the frequent power outages. In any event, when the fire brigade arrived, they had brought no water with them. The Mujurus and others are now calling for investigations into General Solomon Mujuru’s death, even calling for outside help with the investigation. It will be very unlikely that the same careful attention to justice and truth finding will be afforded Maxwell Ncube’s family. He was buried in his home village of Ntenezi in Zhombe district, without the fanfare of a national hero’s burial. It is also unlikely that Mujuru’s death will be carefully investigated, but for different reasons.

As the news of Mujuru’s death began to be processed, it immediately started a debate in the press over his contributions to the Zimbabwean state and ZANU-PF. What is most noticeable are efforts to paint Mujuru as a moderate within the ZANU-PF Politburo and as the only ZANU-PF leader able to restrain the more militant factions, including Mugabe himself. For that reason his death seems to represent a warning of worse days ahead. Mujuru was seen as level headed about the need to cooperate with the MDC, with the recent example of slowing down the call for immediate elections.

In order to paint Solomon Mujuru as a moderate in ZANU-PF, most commentators went back in history to show how, at key moments in the formation of the Zimbabwean State, Mujuru avoided the excesses of Mugabe and others in the inner cabinet. As the first black General of the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) from 1980 to 1992, some see him as having stayed clear of involvement in the Gukurahundi in 1983-85 because it was the infamous Fifth Brigade and not the ZNA who were the main perpetrators of mass killings in Matabeleland and Midlands provinces. An alternative position by Sidingilizwe Mthwakazi on Bulawayo24 suggests caution for those who praise Mujuru too much for having no role in the Gukurahundi. Some key commentators, usually quite critical of ZANU-PF, seem to be motivated more by gaining favor with his widow’s faction in ZANU-PF than with the reality of the Gukurahundi:

“All along, we have been saying it is the former ZAPU leaders that remained in ZANU-PF that are letting down the victims of Gukurahundi. Therefore, it came as a great shock to hear Dumiso Dabengwa and particularly joined by Welshman Ncube in singing from the same apologists’ hymn book. We cannot resolve the Gukurahundi issue by choosing to cherry pick perpetrators. Instead, there is a need to fully address the matter and give an opportunity to the victims to narrate their experiences.”

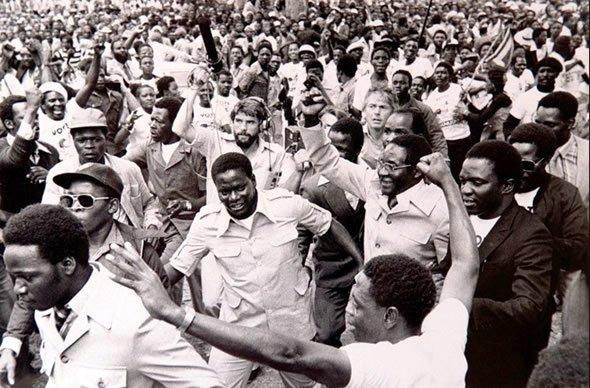

That Mujuru began as a leader of Joshua Nkomo’s ZIPRA army before joining the command of ZIPA and ZANLA is often suggested as part of his accommodating and selfless commitment to the nation. Those who know the history of the nationalist movement best, particularly Wilf Mhanda, the former ZIPA leader who was imprisoned by Mugabe and Mujuru in Mozambique in 1977, and whose memoir, Dzino, was launched coincidently on the same day as Mujuru’s death, helps to illuminate the Machiavellian skills Mujuru displayed during the liberation war to promote Robert Mugabe as the political leader supported by the liberation forces. The senior leader of ZANLA, Josiah Tongogara, died just prior to the return of the ZANLA leaders to parti cipate in the 1979 elections. The photo circulating of Mujuru, Mugabe, and Emmerson Mnangagwa campaigning in the townships of then Salisbury, captures the victory of these three comrades in consolidating power within ZANLA as they moved towards an election where they would come out victorious over Nkomo’s ZAPU and Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s ANC.

cipate in the 1979 elections. The photo circulating of Mujuru, Mugabe, and Emmerson Mnangagwa campaigning in the townships of then Salisbury, captures the victory of these three comrades in consolidating power within ZANLA as they moved towards an election where they would come out victorious over Nkomo’s ZAPU and Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s ANC.

One of the main reasons Mugabe continued to listen to Mujuru was that he owed Mujuru a great deal for making sure Mugabe remained at the top of the liberation movement, starting with Mugabe’s quick advance from relative political obscurity to leadership at the Geneva Conference in 1976. Mujuru allegedly also helped Mugabe during the internal rebellions and attempted coups in the liberation movement, as well as assisting in removing threats from Rhodesian and South African attempts to assassinate Mugabe and destroy ZNA’s Air force between 1980 and 1983. Liberation wars are messy and the politics of independent Zimbabwe were no less messy given the amount of violence and “˜extrajudicial killings’ occurring in Southern Africa at the time.

Mugabe’s creation of the Central Intelligence Organization under Minister of State Security, Mnangagwa in 1982 was meant to counter the infiltration of South African spies and deal with internal political threats. The development of the Fifth Brigade under North Korean trainers to carry out a campaign against Nkomo’s ZIPRA dissidents in March 1983 was the most dramatic of these efforts, particularly given the extent of terror and violence directed at civilian populations. General Mujuru is now being remembered as not having had a role in Gukurahundi, but the portrayal of him as a peacemaker may be overblown. He was committed to removing former ZIPRA soldiers from the ZNA, as Joseph Lelyveld a New York Times reporter, indicated in a March 12, 1983 article.

“Perhaps the most important immediate question is what will happen to the 13,000 former Nkomo troops who still make up nearly 30 percent of the national army. In a recent closed session with his officers, Gen Rex Nhongo, the commander, suggested that they all be discharged. The number of political motivated armed deserters is not believed to exceed one thousand as yet. The government, which has not come up with anything resembling a political strategy for dealing with the problem it has made for itself in Matabeleland, realized in time that it might gravely complicate its difficulties if it cashiered 13,000 troops on what would be seen as essentially ethnic grounds. But it does not trust former Nkomo soldiers and it now makes sure they are given no combat role in Matabeleland.'” NYT, March 12, 1983

Not surprisingly, Mujuru’s commitment to purge ZNA of former ZIPRA is not as well remembered by ZANU-PF leaders and others as his having been trained as a ZIPRA leader in his early days.

The language used in the eulogies at Mujuru’s Heroes Acre funeral by current ZANU-PF leaders reflects the careful selection of words to define the Zimbabwean nation. Take, for example, a quote by Media, Information and Publicity Minister Webster Shamu:

He [Mujuru] was truly patriotic, always prioritising national interest before personal. As a businessman and a politician, he was guided by true African principles and ethics of loyalty to one’s people, respect for traditional and national leaders, no-regionalism fairness and sovereignty.”

One might wonder what “˜no-regionalism fairness’ entails, and what limits are implied by the “ethics of loyalty to one’s people”, and whether or not these two attributes are compatible in the Zimbabwean political landscape? Minister Shamu’s comments also beg further questions. Does fairness imply nepotism? A Zezuru ethnic loyalty? Special projects for one’s birthplace? Who in Zimbabwe defines “one’s people”? These are some of the limits of nationalist rhetoric as practiced among the securocrats and the ZANU-PF insiders. Former General Mujuru was so powerful because he was both.

Commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, General Constantine Chiwenga is reported to have said that Mujuru, “…loved peace and was at the forefront of condemning political violence. The ZDF Commander challenged Zimbabweans to uphold peace by desisting from acts of violence.”

These sorts of words are expected at a funeral, but they seem somewhat Orwellian given the fact that Mujuru was the most successful of the liberation war leaders to use the security forces as a means to accumulate wealth in post-Independence Zimbabwe. The pattern he and others established has, unfortunately, remained the primary route of accumulation by the securocrats in Zimbabwe. This history is well documented, and works by Daniel Compagnon, Scott Taylor, and Norma Kriger come to mind as starting points on the military elite’s accumulation strategies. [1]

Political scientist David Moore recently relayed to me stories he was told in 2004 by former colleagues of Mujuru, such as Patrick Kombayi””whose life was threatened for supporting the Zimbabwe Unity Movement (ZUM) in the early 1990s. Moore reports that Kombayi remembered Mujuru’s ability to make things happen. When ZANLA soldiers were starving in camps in Mozambique, Mujuru asked Mozambican President Machel’s permission to shoot an elephant to feed the starving soldiers; once the soldiers recovered from kwashiorkor, they continued the practice and gained permission to kill more animals. As Kombayi told it, Mujuru had the authority to sign bank accounts for ZANU-PF in London, and it became known that he was having rhinos killed for their horns, selling them to dealers in the Gulf States on the way to London, and depositing the funds in London. Kambayi did not know if the funds went to ZANU-PF accounts or to Mujuru’s but the story itself shows resourcefulness and a business sense that would become the hallmark of Mujuru’s rise to the top of the militarist-accumulators.

Moore also relates a story he heard from a British military trainer who was part of the British Military Advisory and Training Team-BMATT””that was based in Nyanga in Eastern Zimbabwe from 1980 to 2000. The trainer related to Moore that he saw how corruption worked in Zimbabwe by observing Mujuru’s distribution of military jeeps to his subordinates. “One of the keys (pun not intended, but you will see how it comes up) to his corruption and control was executed in this way: he would give jeeps to his subordinates for their own use – but he made it very clear that he had a set of keys as well, and that if any of these proud new owners of jeeps did anything untoward the jeep would be taken away from them.” This story may seem tame enough, but it indicates how patronage worked to build loyalty to the generals and how then loyalty turned to new forms of accumulation, and these were always connected to using violence to defend ZANU-PF as the sole political power in the nation.

After the Gukurahundi of the 1980s, the violence against white farmers, their workers, and MDC and other activists in the 1990s and 2000s has shown how this “guns equal money” formula worked so well for securocrats. Diamond and gold mining contracts obtained in return for defending the Kabila regime in the DRC were a boost to this formula””and SW Radio Africa journalist Lance Guma reports of the continued saga of DRC gold in the Mujuru business empire. The extremely rich diamond deposits in Zimbabwe have been incorporated using violence and the military for the benefit of the Mujurus and other securocrats. [2] Speculation that Mujuru’s death may have been related to a diamond deal or control over the diamond mines has been put forward as a “non-political” explanation of his death, but there is no way in Zimbabwe to separate these accumulation/expropriation strategies from ZANU-PF internal politics.

There has been some mention of the irony that Mujuru died in a house fire on a farm in Beatrice that was “accumulated” by forcing the white owner, Guy Watson-Smith, to clear out in 2001. Watson-Smith’s comments on the fire have been widely dispersed on the web, where he lists the assets on the farm that he was forced to leave behind. After 10 years of legal battle, Watson-Smith never received compensation for his farm’s assets:

“Those assets included all of our breeding cattle (460 head), game (600 animals), our tractors, vehicles, equipment, irrigation equipment, stocks of fertilizer and diesel, coal and so on. It was independently valued by Zimbabwe’s top valuers at US$1.7m in 2001.”

The drama of Zimbabwe’s liberation war leader being found dead in a farm house that had been taken over 10 years ago reminds Zimbabweans of the intimidation, beatings, and deaths, which often included burning of the main farm house or those of farmworkers, that were utilized to obtain many farms in the first place. It also highlights the precariousness of this accumulation by Mujuru’s generation and those younger securocrats and ZANU-PF leaders now jockeying for control of the party. Mujuru’s accumulation (or is expropriation a better word for it?) was not limited to this one farm. In addition, the River Ranch diamond mine is another asset expropriated by Mujuru. A business and political culture that has developed since 1980 in Zimbabwe links accumulation with notions of “rights” to accumulate that were denied in the past. Taking part in the liberation war then became the basis to exercise the right to accumulate after independence. The logical expression of this in a country that has chased away so much business talent and investment, is to shift from accumulating farms to accumulating mines and businesses, as exemplified in the terminating of the operating license of Canadian-owned Blanket Mine over the past few days.

One of the most perceptive opinions on Mujuru’s death comes from Zimbabwean law professor Alex Magaisa who carefully considers how the nation comes to terms with the mixed message of Mujuru’s contributions. An estimated 25,000 people turned out for Mujuru’s funeral, certainly a testament to his popularity. Magaisa concludes:

We have witnessed this week a moral dilemma for the nation. I for one was swayed by the celebratory aspects not only of the liberation war hero but also of a man who represented an important counter-balancing factor within one of Zimbabwe’s most influential political organisations. There is a collective sense of apprehension of how the void his loss has caused will affect politics.

I have also, over the last few days, come to understand and appreciate the narratives of discontent represented by some compartments of the nation. It would be reckless if we did not attend to those issues. It would be clear negligence toward future generations if we dismissed them out of hand. It would be a great legacy if the demise of the military and political giant caused us to think more deeply and act more decisively on these national questions.

Those involved in international policy making on Zimbabwe should reflect on Magaisa’s commentary in New Zimbabwe, particularly for the call for further investigations into the Gukurahundi–and other “knowns” that are typically left as “unknowns” in a country where speaking about these unknowns to those in power — speaking truth to power–only seems to surface for a brief moment after the death of another ZANU-PF hero. There is now a real possibility of future violence in defense of the accumulation of wealth and assets as ZANU-PF hardliners, and those who have accumulated in similar ways, will likely choose to attack those in ZANU-PF whom they see as potentially cooperating with the opposition, as well as mobilizing violence against the opposition. Unless the Government of National Unity was somehow suddenly empowered to investigate and met out justice in both the Mujuru and the Ncube deaths based on thorough police investigations, the idea of “power sharing” in this climate seems like empty words. That is why SADC and South Africa in particular can no longer let the situation continue to deteriorate. Nor should the US, the UK, and the EU, the “˜friends of Zimbabwe’, stand by and wash their hands of Zimbabwe.

[1] Daniel Compagnon, A Predictable Tragedy: Robert Mugabe and the Collapse of Zimbabwe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010); Scott D. Taylor, Business and the State in Southern Africa: the Politics of Economic Reform (Lynn Rienner, 2007); Norma Kriger, “From Patriotic Memories to “˜Patriotic History’ in Zimbabwe, 1980-2005“ Third World Quarterly, 2006 Vol, 27, No 6, pp 1151-1169.

Timothy Scarnecchia is the author of The Urban Roots of Democracy and Political Violence in Zimbabwe: Harare and Highfield, 1940-1964 (University of Rochester Press, 2008) and an associate professor of History at Kent State University.