#StopKony2012: For most Ugandans Kony’s crimes are from a bygone era – By Angelo Izama

Over the last few days millions of people have thronged to watch a video put together by the California based NGO and media company Invisible Children about one of the world’s most notorious criminals, Joseph Kony.

Over the last few days millions of people have thronged to watch a video put together by the California based NGO and media company Invisible Children about one of the world’s most notorious criminals, Joseph Kony.

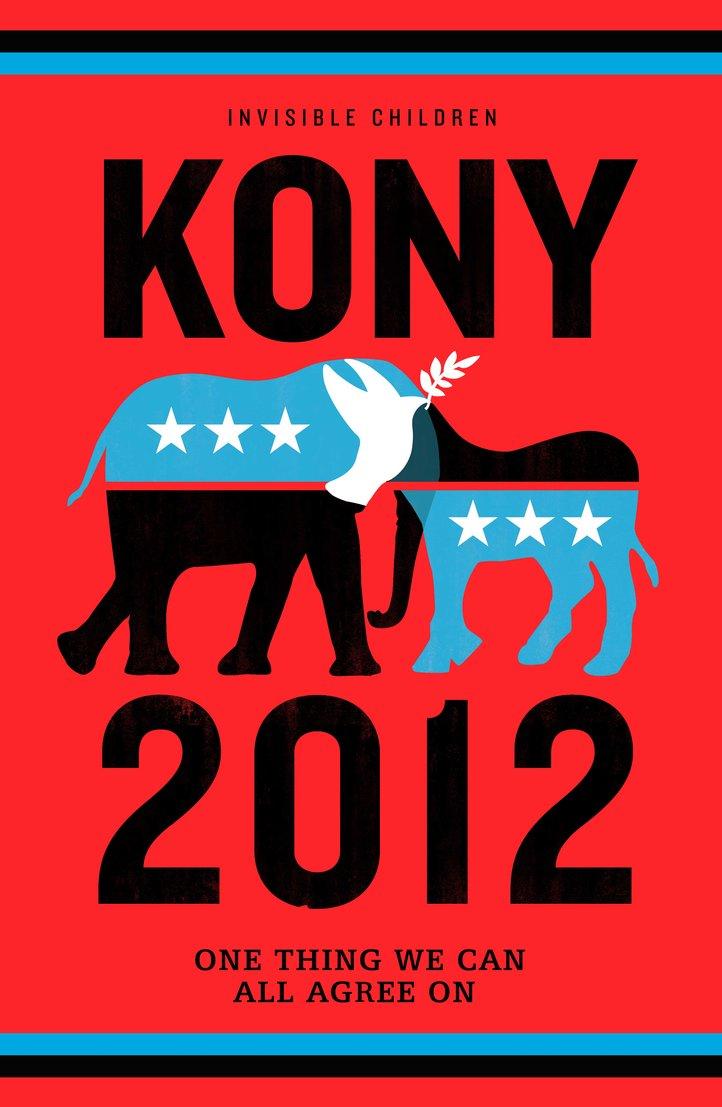

Since the 30 minute video went up, supporters of the company have flooded twitter and facebook promoting the capture of Mr. Kony. According to Invisible Children, the aim is to make Kony so famous that his capture would be inevitable. In one respect this seems to be working – the campaign is capturing the imagination of a certain demographic, largely young college kids. Most of them look to campaigns such as this as an opportunity to do some good in the world and make it a better place. And now even P.Diddy has joined #StopKony2012.

Not since Idi Amin Dada and perhaps the “˜Kill the Gays Bill’ has Uganda gained such a high profile in the news. Amin, the Ugandan dictator, accused of cannibalism (amongst other things) is still just about in possession of the top spot, but Kony is gaining fast.

To call the campaign a misrepresentation is something of an understatement. While it draws attention to the fact that Kony, indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court in 2005, is still on the loose, its portrayal of his alleged crimes in Northern Uganda are from a bygone era.

At the height of the war – especially between 1999 and 2004 – hordes of children took refuge on the streets of Gulu town to escape the horrors of abduction and brutal conscription to the ranks of the LRA. Today, most of these children are semi-adults. Many are still on the streets with a very different problem to deal with – unemployment. Gulu has the highest numbers of child prostitutes in Uganda. It also has one of the highest rates of HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis.

Six years ago children in Gulu would have feared being forcibly conscripted into the LRA, but today the real ‘invisible children’ are those suffering from “Nodding Disease” – an incurable neurological disease that has baffled world scientists and attacks mainly children from the most war affected districts of Kitgum, Pader and Gulu.

It’s true that since the theatre of Kony’s operations shifted from Northern Uganda (in December of 2005) to neighbouring countries he has continued his mayhem. According to the United Nations, increased attacks in the DRC’s Orientale province have led to thousands of displacements and abductions, including children. However, the LRA leader is already the subject of an international manhunt by a joint force of Ugandan, Congolese, Sudanese and Central African troops. This effort is assisted by US combat troops deployed there since October 2011. Ironically, the Ugandan army uses former child soldiers, ex-LRA abductees, to hunt him down (with some success.) So why the misleading campaign? Why now? Who does it profit to market the infamy of a man already famous for his crimes, and whose capture was already on the agenda?

Critics of Invisible Children are also likely to be critics of foreign aid, and by extension the place of Western charities in the mis-education of Western publics about the realities of Africa. The real danger of the game-show type “˜pornography of violence’ that Invisible Children has made so appealing is that it has a dangerous hold on policy types in Washington DC whose access to nuanced information and profiles of issues is similarly limited.

Recent examples of the impact of evangelizing NGOs can be seen from the distortions of the Save Darfur Coalition to an attempted mining ban in the DRC. The simplicity of the good versus evil narrative, where good is inevitably white/western and bad is black or African, is also reminiscent of some of the worst excesses of colonial era interventions. These campaigns don’t just lack scholarship or nuance; they do not bother to seek it. As a colleague once said to me, a campaign such as this could not be mounted around peace in the Middle East because it would require actual scholarship and knowledge of the issues.

Many African critics are unsurprisingly crying “˜neo-colonialism!’ This is because these campaigns are disempowering of their own voices. After all, the conflict and suffering affects them directly regardless of whether or not if they hit the re-tweet button. The Kony2012 campaign will primarily succeed in making Invisible Children, not Joseph Kony, more famous. It will also make many, including P.Diddy, feel like they have contributed some good to his capture. For many in the conflict prevention community, including those who worry about the further militarization of Central Africa, this campaign is just another bad solution to a more difficult problem.

Angelo Izama is a Ugandan journalist, writer and founder of the human security Think Tank, Fanaka Kwawote based in Kampala.

[…] on this whole Kony 2012 phenomenon can be found in this great article from The Atlantic, and in this great post from African Arguments. Now I’m not against the idea of raising awareness about the […]

[…] https://africanarguments.org/2012/03/08/stopkony2012-for-most-ugandans-konys-crimes-are-from-a-bygone… Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

[…] Izama, a Ugandan journalist, believes that Kony 2012 is a form of ignorant campaigning that leads to the “mis-education of Western publics about the realities of Africaâ€. He asserts […]

Dear Izama,

Thank you for your comments. I am friends with a Ugandan woman, Mariam Mukalazi, who works with women who have been displaced by war and have also been physically and sexually abused in Northern Uganda, Rwanda and the DRC. She has seen firsthand the tragic effects of the violence to children and women. I know that the situation is more complex than the Stop Kony film expresses. I also have heard about the fallout from the video and the criticism and then Jason’s suffering a psychotic break because of the stress post-video.

There is a very delicate balance between bearing witness to crimes and speaking out, and creating a neo-colonialist atmosphere, albeit unintentional. The question is how can we as world citizens who perceive ourselves as interconnected, speak up for and/or support those who are being marginalized?

I’m a member of the Global Women’s Leadership Network out of Santa Clara University and was in the inaugural class for Women Leaders for the World in 2005. Since then I have sponsored four women to the program; the most recent will be my Ugandan friend, assuming she will be granted a visa (she was turned down in 2006). The mission of the GWLN (www.gwln.org) is Whole Woman, Whole Leader, Whole World. 139 women from 35 countries have attended the program.

The women who come to the program (there have also been two men — one, a Masai elder)are already leaders. The program offers additional tools and resources as well as provides a network of support. My position is that women — and especially women in the developing world (I’m not crazy about the term but use it for lack of a better phrase) — are amazingly strong, powerful and resourceful. Given the tools and the emotional support, they can move mountains.

What can we, as women, do to speak up against crimes to our most vulnerable citizens? How can we effect change without being perceived as naive or “do-gooders?” I’m interested to hear your views.

Regards,

Patricia Rain