“˜There Was a Country’: a review of Chinua Achebe’s Biafran memoir – By Ike Anya

In our house in Nsukka, the small university town in eastern Nigeria where I grew up, my parents’ bedroom harboured a cupboard, reached only by standing on a stepladder. In that cupboard lay a battered brown leather satchel, filled with memorabilia from Biafra. I remember Biafran stamps, currency notes and coins, photographs, receipts, letters and a small green hard backed pamphlet: The Ahiara Declaration.

In our house in Nsukka, the small university town in eastern Nigeria where I grew up, my parents’ bedroom harboured a cupboard, reached only by standing on a stepladder. In that cupboard lay a battered brown leather satchel, filled with memorabilia from Biafra. I remember Biafran stamps, currency notes and coins, photographs, receipts, letters and a small green hard backed pamphlet: The Ahiara Declaration.

From time to time, under conditions of great secrecy, the satchel would be brought down and my brothers and I would be allowed to rummage through it as my parents told us stories of their harrowing experiences during the war. We would look at photographs of friends and family “lost” in the conflict, or during the massacres of Igbos that preceded it. We would marvel at the lightness of the Biafran coins. I don’t remember my parents explicitly saying it, but somehow it was communicated to us that the satchel and its contents were not things to be discussed outside the family home.

In Nigeria in the 1970s when I grew up, Biafra was only talked about in hushed tones, in an atmosphere of an unspoken fear that talking about it could bring reprisals.

A few weeks ago, I was lucky enough to be invited to an early rough-cut screening of the film version of Chimamanda Adichie’s book, Half of a Yellow Sun. At the end, in the darkened room in Soho, as I joined others to congratulate the director Biyi Bandele, I found myself hugging him instead and felt to my embarrassment, tears running down my cheeks. As I apologised, avoiding the bemused stares from some of the staff at the venue, I explained to Biyi that I had felt such a powerful reaction because the story he was telling was the story of my family – of my parents and grandparents.

That evening, as on the phone I described my feelings watching Biafran refugees fleeing the university town of Nsukka to my mother, who had herself fled the town with my father and elder brother in 1967, she said “I am glad that our story is going to be told, that the world will remember”.

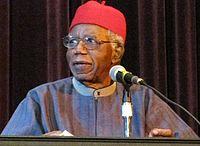

Chinua Achebe’s new book There Was A Country: A Personal History of Biafra emerges into this landscape of memory and remembrance, forty two years after the war ended. In the book Achebe, a few weeks before his 82nd birthday, finally sets out to tell the story of his Biafra. The format he adopts is novel – involving a rambling mix of anecdotes, summarized histories, analysis, reportage, declamation and haunting poetry. In some ways, reading the book feels like I imagine spending an hour or two chatting with the distinguished novelist might.

He roams from the story of how Nigeria came to be, to his schooldays and burgeoning friendships with prominent figures like the poet Christopher Okigbo, whose presence looms large through the book. Interspersing the historical account is the story of his father, one of the early Igbo converts to Christianity, and his experiences growing up with newly Christian, trailblazing parents caught between the old traditions and cosmology of the Igbo people and the new Christianity. The personal glimpses into his early life are hugely enjoyable and indeed tantalizing – often outlined so succinctly, that he leaves the reader greedy for more detail.

Approaching the events leading up to the war – the descent of the first post-independence Nigerian government into an abyss of corruption and misrule; the role that the colonial government played in setting the stage for this descent and the first military coup in 1966 – he acquires a less personal and more straightforward recounting tone. This continues until the latter part of the book, when he begins to describe the counter-coup of July 1966, the massacres of Igbos that followed the coup, the failed attempts at negotiating peace and the subsequent declaration of independence and the harrowing consequences that followed.

Achebe, as is his right, does not pull any punches, although he does make some concessions to alternative points of view, especially in relation to the legacy of colonialism and the moral imperative on writers to produce committed literature. He is less conciliatory on the question of whether the actions of the Federal Government of Nigeria during the war constituted war crimes and, possibly, genocide. He is scrupulous in naming the officers and individuals responsible, and where possible provides their viewpoints based on news and other reports.

He also highlights the role played by Western countries and the international community. And he challenges the popular perception that General Gowon’s “No Victor, No Vanquished” policy at the end of the war in 1970 led to the successful re-integration of the Igbos into Nigeria, highlighting the egregious government policy which wiped out the savings of every Biafran who had operated their bank accounts during the war with an “ex- gratia” payment of just 20 pounds. He is also laser sharp in his conviction that part of Nigeria’s problem stems from its anti-meritocratic suppression of the Igbo people, and the refusal of the country to face up to insalubrious aspects of its history, issues that he argues continue to haunt it.

Of particular interest are the snippets that emerge of life in Biafra – the intense emotional connection of a people united by the fear and anger at the massacres, the ingenuity of the engineers who fond ways to refine petrol or build bombs and the efforts of artists and intellectuals to contribute to building a new nation. He also describes his own forays to foreign capitals to seek their support for the Biafran dream and the eventual withering and death of that dream. Sprinkled through the book are excerpts from a series of interviews commissioned by the Achebe Foundation with many of the key players in Nigeria’s history. These, when eventually published, should provide a rich resource and other perspectives on the events that the author describes.

The final section of the book picks up on Nigeria’s journey since the end of the war, dipping into the failures of governance and the consequences, raising several questions that need to be addressed for the future.

The book could benefit from a closer proof-reading and fact-checking process by an informed editor. Irritating errors crop up like “maul over” for “mull over” “deferral” for “federal”, “Iwe Ihorin” for “Iwe Irohin” and St Elizabeth’s Hospital for Queen Elizabeth Hospital, but these do not detract from Achebe’s attempt to present, from his perspective, an account of those dark days. As he says in the book, “My aim is not to provide all the answers but to raise questions and perhaps to cause a few headaches”. It is clear that this is his book, his view and his own particular nostalgic ramble. Ultimately, it is important that he has shared it, warts, unevenness and all. In doing so, Achebe has helped bring the contents of my parents’ brown satchel back into the open.

Ike Anya is a Nigerian public health doctor and writer based in London. His essay People Don’t Get Depressed in Nigeria appears in the current edition of Granta Magazine

First review I’ve read that acknowledges the writer’s right to put forward his own perspective. Thank you.

I have heard quite a number of people get up in arms ahead of reading Achebe’s new book & its amusing to me that they do not realise how very much they emphasize his relevance by doing that. I love Achebe’s writing & think his story of Biafra has come at just the right time that Nigeria can benefit from it. I have not heard a pip out of anyone as to why a movie about Biafra is being made (at this time)yet everyone queries Achebe’s right to tell a story that obviously needs telling. Sadly, I have read all sorts of ignorant drivel from (unfortunately!) many Yoruba people who (as always) act as if their brain took a leave every time Awolowo’s name is mentioned. The greatest shocker for me was sitting and talking to my husband about the book and why we Yoruba are having such a violent reaction to it and he (very violently!) asked if I had taken leave of my senses….sigh! It has since been a very healthy debate in our household and I look forward to reading this book! So much so, I pre-ordered a Kindle version. I do not hate Awolowo but neither do I revere him as I think he was just a man (just like my father) who was intelligent and had ideas that could benefit this nation but he failed because of his tribalism and this particular failure is the very thing that makes him celebrated and I wonder why? Your review is made poignant by your experiences with your family & I think its truly beautiful…..Well done!

Ike, your narrative is smooth and fascinating. I like your approach and treatment of the subject (and I envy that you’ve watched the Biyi bandele flick),but I would have liked read more quotes from the book itself. Any chance that your parents’ satchel bag exists to date?

Very poignant.

Great review and summary. I think all Nigerians of whatever hue or extraction, should appreciate this book all the more, with this review. Achebe has every right to tell his story; what is both a very personal experience on the one hand, and communal experience (shared by other Igbos who lived through, or had family and loved ones that were impacted by the war) on the other. I will suggest that for those Nigerians who read this book – I am already halfway through it – particularly the generation born after Biafra, that you attempt to read it without any pre-conceptions or indeed hang-ups. It’s a very important part of Nigeria’s history that should be at the heart of whatever education on or introduction to Nigeria anyone receives. If ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’, was the lay-man’s (but nevertheless, excellent) introduction to the Biafra story, ‘There Was a Country’ is the closest to a reasoned guide book on Biafra, from a stellar writer.

I haven’t read the book yet, but I’ve read a couple other reviews as well as Ik’s. This Achebe Book is a gunpowder keg. It’s the truth and we all stand by it, but make no mistake. It’s not going to foster any collective soul-searching nor national healing. On the contrary, I’d expect more riots, finger-pointing, denials, etc., and here’s why:

Just like Ahmadinejad denying the Holocaust ever happened, the average Yoruba will quickly jump to Awo’s defense on his anti-Biafran policies i.e.

“Food & economic blockade” to wipe out the Biafran children & “ex-gratia” to wipe out surviving Biafran adults after the war. Ditto his protege Bola Ige, who followed Dr, Akanu Ibiam’s Biafran aid missions around the world telling them not to honor any food or aid appeals for Biafran children, that the Nigerian army will shoot down their planes if they try. Up until his infamous presentation on justification of food & aid blockade to the 4th Upsalla assembly of the World Council of Churches in Sweden. Deny the children food in God’s name, Amen!

The “upper” middle belt minorities have an even bigger one to swallow. On one hand, their own Danjuma killed both Ironsi (drawing Igbo Ire), and his host, Fajuyi (drawing Yoruba anger) in cold blood, same night, and then their own incredibly naive and inept Jack Gowon was the project manager of the ensuing war.

The South Eastern minorities have their own axe to grind with everyone — Adaka Boro was already in the process of emancipating them from a Nigeria they did not belong to, only to now add annexation by Biafra to their problems! Through Elechi Amadi’s eyes in “Sunset in Biafra,” the Igbos/Biafrans was a fearsome locust plague that needed to be checked at all costs, and it was their right and entitlement to do so! So how does the Igbo “parasite” even dare wag a finger at Diette Spiff on the abandoned property issues of post civil war Rivers and South Eastern states?

Then among the Igbo/Biafran community, we continue to squabble over who should wear the “Efulefu” name tag. Was Ukpabi Asika a hero or sellout? whichever, whatever, it was his prerogative. Did Ike Nwachukwu fighting on the nigerian side actually participate in Killing Igbos at the Asaba massacre? And then come back to seek Igbo support to run for president? Where’s the cry of anguish and outrage from super permanent secretary Asiodu after his village was sacked by the Nigerian army and his female siblings were publicly raped and his brothers and children butchered in cold blood by the agents of the government he worked for?

And then we speak of shame itself. Joe Igbokwe aptly sums it up in his SaharaReporters article, War is Imminent, “I saw it all and witnessed the evils of civil war. Women became whores, girls became mothers, lizards became meat, every leaf of any plant became vegetables…”

There’s a plethora of shame and Napalm to go round, Achebe just struck a matchstick!

I have tried to read as many previews and reviews of Achebe’s book that I can lay my eyes on and this is by far the most incisive but even this does not satisfy my curiosity.

Which leads to my request: Please can anyone who has read the book advise me, apart from his insidious allegation against Awolowo, what else was new in the book? How is it different from all the numerous Civil War memoirs we have read before now?

I need to know before I place an order.

Having just taken delivery of my copy of the book, this review has increased my eagerness to read it in spite of my very busy schedule. The review sounds objective. I believe that people have a rights to tell their stories. ANyone who holds a contrary opinion can publish his version without calling people unprintable names for daring to speak out.

@Boko. Interesting comment. I am certainly by no means an expert on Nigerian history or Biafra for that matter, and I see you’re commenting from the point of view of someone who has some real additional insights on into this topic. However I have a couple of queries; first, what do you mean by the ‘average Yoruba’?; for the generation born long after Biafra, the various labels and ethno-linguistic /ethno-political battle grounds that have been drawn in Nigeria, are that were the offspring of the war mean much less to us than they did to our parents, probably. Second, I have personally not come across many ‘Yoruba’ who defend Awo as you put it in the very specific context of his policies towards Biafra, when, I have just read, he was federal commissioner of finance during the war. You suggest that the ‘average Yoruba’ would rush to Awo’s defence. However, in actual fact, the ‘average Yoruba’ pretty, much like the ‘average Nigerian’ isn’t probably as deeply informed on Nigerian history, and specifically the Biafra context as they should be. Second, on the positions you cite as being held by the ‘upper middle belt minorities’, the ‘south eastern minorities’ and the ‘Igbo Biafran’, my biggest fear is that the debate on Achebe’s book – not necessarily the book in itself – actually risks polarising and dividing us further. Essentially, it is this very sub-plot to the Biafra story, that you mention here, that is all the more concerning for ‘Nigeria’s’ future coherence as a state – if at all.

[…] SOURCE: AFRICAN ARGUMENTS […]

[…] Anya also wrote for African […]

[…] Approaching the events leading up to the war – the descent of the first post-independence Nigerian government into an abyss of corruption and misrule; the role that the colonial government played in setting the stage for this descent and the first military coup in 1966 – he acquires a less personal and more straightforward recounting tone. CONTINUE READING POST HERE […]

https://cialiswithdapoxetine.com/ cialis tablets