Kenya transfixed by its illiberal and rightwing gang of eight – By Daniel Waweru

It’s often said that Kenya’s political parties lack any ideological underpinning. The recent pair of Presidential debates shows this false.

It’s often said that Kenya’s political parties lack any ideological underpinning. The recent pair of Presidential debates shows this false.

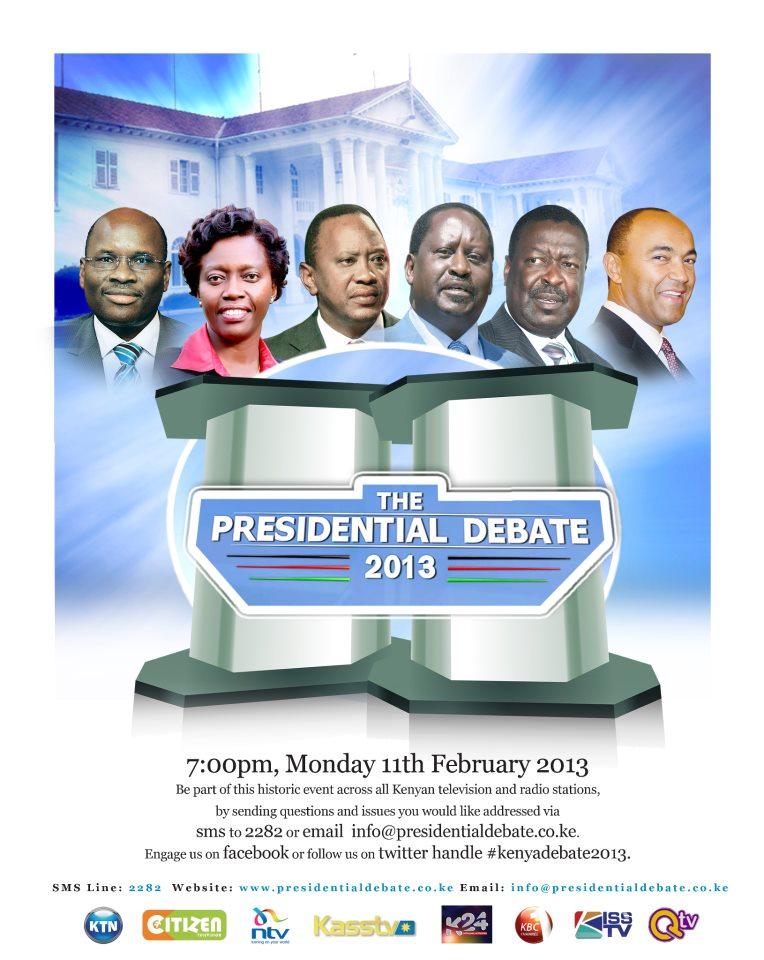

The discussion of economic policy at the main debate, where it emerged that the Nairobi consensus doesn’t significantly differ from the Washington consensus, may have been the clearest counterexample, but the Deputy-Presidential debate, where candidates opposed the Marriage Act, and were happy to express the view that abortion is unconstitutional – on explicitly Biblical grounds no less – was probably the most amusing. Never mind that the constitution, at Art 21(4), explicitly permits abortion in cases where a qualified medical practitioner determines that the life or health of the mother is in danger; the real value of the debates is in laying bare the basic assumptions of the top end of Kenya’s political class.

The trimmings and colour scheme of the debate stage didn’t struggle too hard to distinguish themselves from the setup at a Republican primary. Raila Odinga and Prof. James Kiyiapi claimed, with varying degrees of plausibility, to represent the Kenyan dream. Uhuru Kenyatta wore one of those lapel pins: the sort of thing American politicians do; the sort of thing which sits ill with the nationalism-and-sovereignty theme of his campaign. Paul Muite, apparently intent on demonstrating that the urge to Americanisation had detached him from all contact with Kenyan reality, clasped his right hand to his heart in the American style as the national anthem played before the debate. As every Kenyan schoolboy knows, the posture for a formal performance of the national anthem is attention, thumbs in and facing downwards.

The precedents date back to at least Kenyatta’s reliance on Thurgood Marshall’s legal advice for the framing of the constitution (an episode nicely reviewed in Mary Dudziak’s Exporting American Dreams), and they continued with the naming of the Forum for the restoration of Democracy (FORD) and ODM’s six-sided Pentagon of 2007. In Muite’s performance, a new depth (or height, to taste) has been reached.

There was other amusement and instruction on offer. Martha Karua’s diligence, directness and mastery of her brief produced the best debating performance of the eight candidates: she was able to point out, to the Prime Minister’s evident discomfort, that his party had failed to support the bill through which the government had proposed to set up a local tribunal to try the perpetrators of the post-election violence of 2007. Kiyiapi ably argued his corner when Peter Kenneth, widely regarded as the details and policy guy before the debate, claimed that there was only a misdistribution, not a dearth, of teachers.

Kiyiapi, a former Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Education, laid out the details of the shortfall. Indeed, apart from a purple patch halfway through the debate when he exposed the steep growth in recurrent expenditure, and made a specific promise to cut KES 150 billion of it, Peter Kenneth did poorly: he seemed arrogant, hawkish (overcompensating, perhaps, for his image as a bit of a wimp) and windy — unable concisely to state his plans.

All the professional politicians on stage came out for some variant or other of Uhuru’s position on the matter of his eligibility, in light of the ICC matter: the common mind most clearly spoken by Prof Kiyiapi when he said that the matter would be decided by the electorate. This joint view made Uhuru’s defence, in the face of fierce questioning from the moderator, less difficult than it might have been. It eased his attempts to defend himself; it removed a significant weapon from his opposition’s armoury; it strengthened his own campaign narrative — so much so that the public endorsement of this view by his opposition probably explains his post-debate success with undecided voters.

Uhuru didn’t debate particularly well — indeed, he was disastrous in parts, as when he claimed that the ICC case was a personal problem; or when replied to Karua’s probing of his eligibility with the claim that he was seeking elective, not appointive, office. (While sound, the distinction was completely irrelevant to the question.) But, given the concurrence of his rivals with substantially the same story that he’s been telling throughout the campaign, it turns out he’s the candidate who most benefited politically from these debates. Martha may have won the debate, and Uhuru the politicking; Kenyans will have to content themselves with the prize of a president picked from this unabashedly illiberal and rightwing gang of eight.

Daniel Waweru is a Kenyan writer and academic.