Mali: dragging the west back in to the War on Terror – By Magnus Taylor

Intervention in Mali may be justifiable on a local level, but is still sold as being part of a global struggle.

A few weeks ago, most British journalists, politicians and foreign policy watchers would have had difficulty accurately positioning Mali on the map or naming its capital city (Bamako). They would certainly have been unable to bandy around the names of Tuareg and islamist insurgent groups, or speculate on the importance of the trans-Saharan trade in drugs and cigarettes. So what has changed, and what does it mean for international policy in this poorly understood region?

Mali – a landlocked, impoverished desert country famous in the west for its music – is the latest country to be subsumed within the rhetoric of the War on Terror. However, the origins of Mali’s crisis lie in long-standing grievances of its marginalised Tuareg minority in the North, the islamist remnant of Algeria’s civil war (largely kept in check in Algeria by its restrictive military regime) and a handful of foreign jihadists who see the Sahara as a more fruitful region of struggle than their own homelands (ranging from Pakistan to Libya and elsewhere in Africa). Ungoverned spaces, akin to the “˜tribal’ regions of Afghanistan/Pakistan or Southern Somalia, particularly those where it is possible to propagate anti-western sentiments, have (with some justification) been a worry to western powers for many years.

Intervention in Mali, in the shape of “˜French-led’ Operation Serval does seem to be motivated, in part, by a genuine desire to stop the kind of unwanted Sharia-based system of control that had taken hold in Mali’s rebel-controlled Northern towns from spreading to the more populous South. This seemed briefly possible when the Islamists made a surprise advance 2 weeks ago, although whether they would have been able to hold this territory for long is doubtful. Second, and of greater “˜strategic’ importance, is the desire to prevent serious contagion in West Africa. If Mali fell to the islamists then what impact would that have on nearby Nigeria? – currently battling its own home-grown (but lower level) islamist insurgency in the north of the country. Whilst Mali may be a dirt poor patch of desert with little international economic importance, Nigeria is Africa’s biggest oil exporter. Neighbouring Algeria sits second on the list.

The rhetoric and thinking produced by the US-led “˜War on Terror’ has been instrumental in producing a concerted, if somewhat delayed, western response (plans had been afoot for nearly a year to launch an African force led by Nigeria, some training for the Malian army is being provided by the EU). Whilst there is little appetite for “˜boots on the ground’ in the US or UK, which both have sizeable deployments in Afghanistan (and had them for many years in Iraq), the French are largely unburdened by this recent history. Operation Serval was launched after a direct request from the Malian government, but it is difficult to believe that there wasn’t a sense that in this patch of Francophone West Africa, it was France’s turn to do the dirty work.

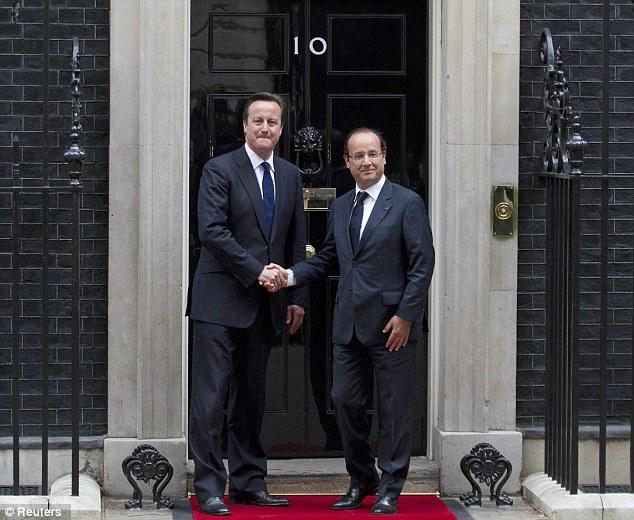

The intervention also represents a further positive projection of French military force in Africa, leaving behind the old corrupt practices of Francafrique which dogged President Hollande’s predecessors, and largely concerned its more affluent ex-colonies (Mali is not one of these). France, along with Britain and the US, also made up the “˜P3′ group of powers which carried out aerial attacks on the forces of ex-Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, and proved instrumental in his fall from power in 2011 – an operation that some analysts have blamed for causing a flood of weapons to reach the Malian rebels, thus making their insurgency possible.

British Prime Minister David Cameron has been outspoken in his analysis of the current problems in the Sahara as part of a “˜global’ fight against islamist terrorism. He made the following statement after the recent hostage-taking episode at the In Amenas gas plant in south eastern Algeria where 6 Britons died (probably a response, of sorts, to France’s action): “What we face is an extremist Islamist violent al-Qaida-linked terrorist group – just as we have to deal with that in Pakistan and Afghanistan…It will require a response that is about years, even decades, rather than months”.

Foreign policy makers would do well to avoid conflating a long-standing crisis of governance in the Sahara, along with the fallout from conflicts in Mali, Algeria (and more recently Libya), with a global terrorist threat now centred on the region. As Jason Burke, author of Al-Qaeda: the true story of radical Islam, states “[Cameron’s words] sounded dated” and bring us back to the immediate post-9/11 days when the enemy seemed clear and action unavoidable.

Whilst it is too early to say whether France’s entry in to Northern Mali will trigger an Afghan-style insurgency, dragging international players into a morass of complex local politics, all those involved would do well to properly understand what the nature of the threat is.

Magnus Taylor is Editor of African Arguments Online.

Taylor you state that

“Intervention in Mali, in the shape of ‘French-led’ Operation Serval does seem to be motivated, in part, by a genuine desire to stop the kind of unwanted Sharia-based system of control that had taken hold in Mali’s rebel-controlled Northern towns from spreading to the more populous South.”

I find this assumption naive and there is a definite risk in taking such political rhetoric at face value. I would direct you towards Gilbert Mercier’s insightful and more critical piece, Obama: No MLK but leading man of humanitarian imperialism“” published in News Junkie on 20 Jan 2013. Mercier states that “In his book “Humanitarian Imperialism,†published in 2006, author Jean Bricmont argued that since the end of the cold war, human rights have been used as a justification for war or foreign interventions (…) the same rationale of humanitarian imperialism is used by Mr. Obama’s NATO ally, France’s President Hollande currently waging a war in Mali.”

Your argument that French military intervention may be largely on humanitarian grounds holds only if you assume, as you do, that “Mali may be a dirt poor patch of desert with little international economic importance”. However this is not true as the Sahara is rich in natural resources. For the clear links between political rhetoric on ‘the war on terror’, military intervention, and neo-imperialist resource grabbing see another of Mercier’s articles, this time specifically about Mali, France’s neo-colonial war for Uranium? published on 14 Jan 2013 in News Junkie. Mercier cites former French prime minister Villepin, who has staunchly criticised Hollande’s approach, saying “How has the neo-conservative virus been able to infect our outlook? This unanimous enthusiasm for war, the haste with which we are doing it, and the deja-vu of ‘war on terror’ worries me.”

It worries me too, and as African scholars I think we should be more aware and critical of how certain leaders are able to play on our sensibilities with such apparent ease.