Africa’s fuel subsidies: Grasping the nettle – By Adam Robert Green

Faced with a rising food and fuel import bill, numerous African governments are reviewing their energy subsidy schemes. Between the end of 2003 and mid-2008, nominal international fuel prices increased more than fourfold, with most of the increase occurring during 2007 and the first half of 2008. Prices have stayed high through the recession, due to geopolitical shocks in North Africa and the Middle East. And fuel costs are only going to increase over time, given the world’s continuing reliance on non-renewable fuel resources and Africa’s lack of capacity in delivering finished fuel products.

Deconstructing fuel subsidies is a cheerless job for any government. Private sector actors and trade unions complain of rising production costs and loss of export competitiveness, while consumers object to rising living costs. Populations are directly affected through higher prices for fuels consumed for cooking, heating, lighting, and private transport. The indirect impact hits the poor, through higher prices for all goods and services for which higher input costs are passed on. IMF estimates suggest that a $0.25 per litre increase in fuel prices equates to a 5.9% decline in household real incomes – hardly a popular move, whatever the long term economic merits might be.

The effect of subsidy removal on all segments of society means few have the stomach to tackle this head on. Egypt’s government is in a drawn-out dispute with the IMF over its fuel subsidy scheme, which could have cost as much as $4.7bn over the first three months of this year. Nigeria’s energy subsidies have also grown at a frightening pace, reaching a 97% yearly growth rate by 2011.

But energy subsidies are often regressive overall, with over 80% of the total benefits accruing to the richest 40% of households, according to one global analysis by the IMF. “Fuel subsidies are a costly approach to protecting the poor due to substantial benefit leakage to higher income groups,” argue the IMF in a report. “In absolute terms, the top income quintile captures six times more in subsidies than the bottom”.

Senegal provides an example of the burden, and inertia effects, of energy subsidy outlays. Subsidies for electricity consumption, as measured by the annual budgetary transfer to the power utility SENELEC to compensate for the tariff gap, amounted to about 1.4% of GDP last year, meaning SENELEC now soaks up more funds than are allocated for new capital expenditure on health or education. And even with this expensive scheme in place, power is expensive and unreliable due to the dearth in private investment; itself a response to the flaws in the subsidy payment framework. A restructuring of SENELEC is imminent, and would allow the government to widen its currently limited safety net programme.

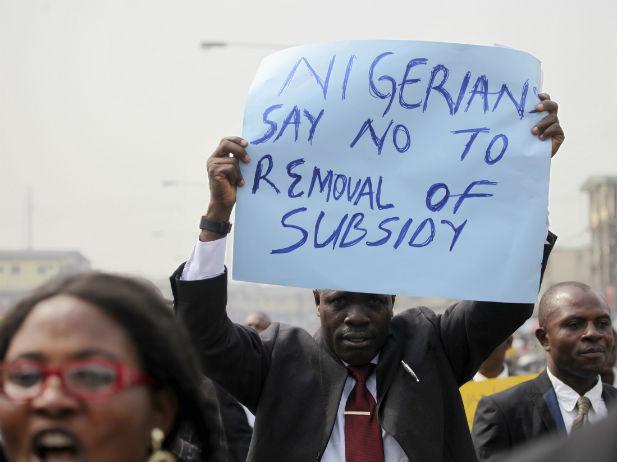

Nigeria’s fuel subsidy, meanwhile, has mushroomed of late. But reforms last year – which led to the highest price jump in fuel in the country’s history, from $0.42 to $0.89 – led to eight days of nationwide strikes supported by a range of groups, including the Nigerian Labour Congress and the Trade Union Congress. In the end, the government reduced the subsidy increase to a $0.63 increase, and many of the gains from the initial removal were lost through the economic shut-down, and corruption in the subsidy reform procedure. A bigger public policy flop is hard to imagine. Little more will happen now, as Nigeria re-enters elections season in mid-2014.

Does fuel subsidy reform unavoidably entail strikes and economic woe? Not necessarily. Several African countries have drawn down subsidy schemes while implementing compensation mechanisms to protect the most vulnerable. In 2004, Ghana’s government announced plans to raise fuel prices by 50%; the increase was pursued in parallel to a targeted anti-poverty programme, including the elimination of primary and junior-secondary school fees, extra funds for primary health programmes, rural electrification and urban transport investment. There was still resistance – notably from trade unions – but a thorough debate led to a smoother reform process overall.

Gabon raised gasoline and diesel prices by 26% in March 2007. A cash payment scheme to the poor was resumed, and assistance to single mothers was increased, as was a microcredit program targeting disadvantaged women in rural areas. School enrolment fees were waived for public schools and investment in rural health, electricity and water supply was accelerated. The public transport network in Libreville was modestly expanded. Finally, Guinea has lowered its budget deficit from 14.3% in 2010 to 3.9% in 2011, in part due to a lowering of fuel subsidies which has been crucial in allowing the government to get a handle on its disastrous public finance inheritance from the previous military regime. Yet social spending has been able to rise in step, with free malaria net distribution to vulnerable populations, immunisation campaigns and lowering of healthcare costs.

While some argue that higher fuel prices would hamper competitiveness, in reality few African countries – with the possible exception of Mozambique – are in a position to use energy as a comparative advantage yet. And ironically, private investment in energy would likely increase if prices were market-determined, as energy companies are reluctant to make major investments when key prices are determined by political whim. By supporting the public purse, drawing down on unsustainable subsidies could also help governments make the much-needed investments in health, education and infrastructure.

Adam Robert Green is Senior Reporter with This is Africa, a bimonthly publication from the Financial Times Ltd.