In Libya anarchy reigns and international engagement is sorely needed – By Jason Pack

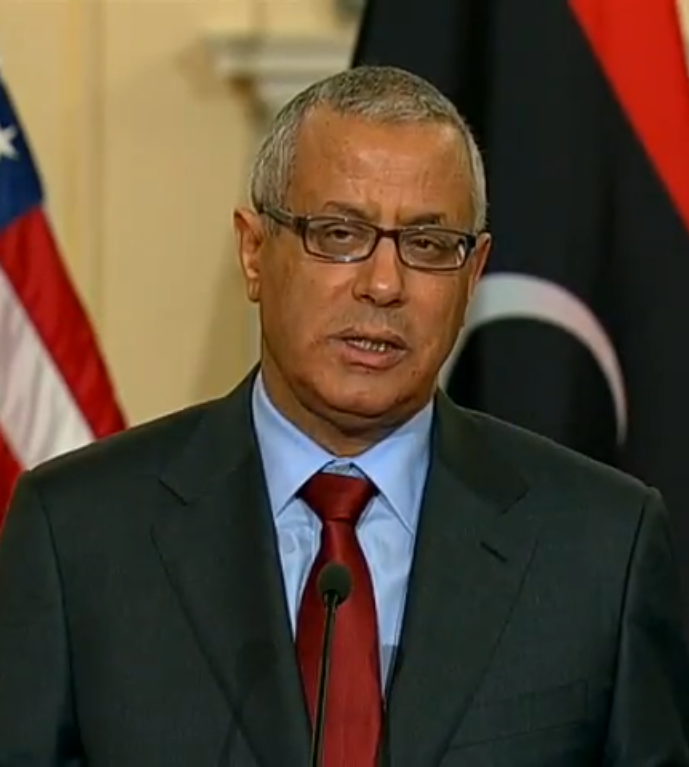

Libyan PM Ali Zeidan must, with international support, assert the supremacy of his government against the continuing power of the militias.

May 2013 was just another humdrum month in Libya. It witnessed more deadly explosions, a prolonged siege of government ministries, the disappearance of a popular militia leader, the closure of the Sebha airport by militiamen as retaliation, a declaration of Cyrenaica’s semi-autonomy by self-styled provincial leaders, the resignation of Libya’s president, and the start of the witch hunt to cleanse the public sphere from those who served the Qadhafi regime in any capacity.

After the hospital in Benghazi on May 12 and on the French Embassy on April 29, foreigners may assume that the security situation in Libya is atrocious and must be the country’s primary problem. Yet, in reality, the transition has been a relatively peaceful affair, despite its clearly anarchic and dysfunctional trajectory. Post-Qaddafi, Libyans are very reluctant to kill their countrymen over ideological or political battles. The attacks on the American mission in Benghazi in September 2012 and at the French Embassy in Tripoli this April were isolated incidents, likely to have been carried out by non-Libyans or by Libyan extremists in concert with foreign actors. Libyan culture is fundamentally conservative and the country’s greatest strengths and weaknesses come from the immense value placed on consensus, tribe, family, town, and region.

Amidst the chaos caused by the weakness of the central government and its inability to police its borders, Libya’s troubles have been exported to neighbouring countries. First in 2012, armed Tuareg militants used Libyan arms to declare the independence of Northern Mali, then Al-Qaeda established training camps in Libya using them as support bases to project their influence throughout the Sahel. Then in 2013, terrorist attacks in Algeria and Niger were carried out taking advantage of the copious arms available in post-Qaddafi Libya, easily navigating the country’s porous borders.

Inside Libya, the recent sieges of government buildings in Tripoli in early May have been used as a cover by those who oppose an orderly and democratic transition. They have seized the opportunity to employ new tactics with a series of night attacks on Benghazi police stations and it is also likely that the May 12 daylight explosion at the hospital was a deliberate attempt to kill ordinary citizens.

These attacks must be viewed against the backdrop of rise of criminal gangs, radical Islamist cells, and extortionist militias, all of which have progressively hijacked normal Benghazi life, enraging the majority of its citizens who have consistently called on the government to disarm the militias and the thugs and restore order.

Whether it can be proved that terror groups ejected from Mali have moved to Libya as stated by the French foreign minister, Laurent Fabius, or that Libyan opponents of the central government are merely expanding their repertoire, Western support is needed more than ever to avoid Libya becoming a new terrorist haven or ungoverned space.

Bloodless coup

From April 28 until May 9, Tripoli witnessed something akin to a bloodless coup as armed protestors blockaded the interior, defence, foreign and electricity ministries, blackmailing the elected General National Congress (GNC) into passing on the debilitating Political Isolation Law. It bars former functionaries of the Qaddafi regime from any political office for the next decade, even if they spent decades as dissidents or human rights activists.

The law represents a nefarious power grab by certain Islamist and militia factions who seek to cripple the existing government by unseating their technocratic opponents who invariably have previous government experience so that these factions may assume political power either directly or indirectly. So far, the strategy is already working. The Libyan President, Muhammad Magariaf resigned on May 27, and many officials are following suit rather than have their names dragged through the mud by investigations.

Nary to be found is a Libyan politician who is willing to publically denounce the militias. All fear for their lives and are scrambling to curry favour of the men with guns.

There is a school of thought that the GNC repeatedly bows to militia pressure because it lacks the necessary firepower to protect itself. The national army is in a mess and the most powerful organs of the security services such as the Supreme Security Council are entirely infiltrated by Islamists who are disloyal to the government. Despite this, there actually are other militiamen loyal to the GNC who would fight to defend the rule of law and democratic procedure. Yet, rather than call upon them, the GNC’s aversion to the use of force against any segment of the Libyan people, no matter how disruptive, has led to its repeated appeasement of its federalist, populist, and Islamist opponents.

Given the relative rarity of lethal violence in post-Qaddafi Libya (rather than threats or intimidation which are commonplace), the increasing boldness of anti-government attacks and the targeting of civilians is all the more shocking. It may signal that the central authorities are on the verge of totally losing control. Alternatively, it may finally spur them to action. They have promised a new mechanism – the bizarrely named Joint Security Room – to coordinate between police and the army in the quest to kick the militants out of Benghazi.

Yet the chances of success appear remote. As these new measures were being announced in mid-May, the Army Chief of Staff’s headquarters were allegedly being attacked by RPGs. Moreover, most members of Libya’s army want to sack their own Chief of Staff, Youssef Mangoush. If the Army is incapable of taking even the minimal steps needed to protect its headquarters or support their boss, and the GNC refuses to call in its supporters to protect its parliamentary building, how can one expect that they will bold action to improve the security situation?

Therefore, despite fine sounding government promises of action against the militias, the endpoint of the chaotic political transition and the return of security has receded beyond the horizon. Ordinary Libyans feel that all they can expect from the government is more upheaval and broken promises.

PM Ali Zidan has pledged a cabinet reshuffle and June will see the start of the witch hunts to first brand and then oust certain officials as Qaddafi remnants. This uncertainty casts great doubt over the timeline and outcome of the constitution drafting procedure.

Power drains away

Prospects for a new democratic Libyan state with functioning institutions governed in line with a modern constitution do not appear to be good. But at the other extreme, and equally unlikely, is something akin to a perpetual state of anarchy as the government melts away to be replaced by competing tribes, militias and various regional and ideological interest groups.

More likely, perhaps, is some middle ground: an unhappy equilibrium whereby different stakeholders come to dominate different institutions such as the security services, oil sector, and border control in a sort of semi-functional, semi-corrupt power-sharing agreement. In this arrangement the men with guns will still exert their influence but by getting the government to rubber stamp their power grabs with a veneer of legality.

The central government has already eviscerated its own power by voting away its right to select the constitutional committee, while the militias, Islamists, and localists are ensconced in their various fiefdoms and appear nearly impossible to dislodge.

Libya’s international allies had the last 20 months to support the liberal central authorities against the recalcitrant militias but were reluctant to engage in capacity building activities out of concern for committing scarce resources or putting their own citizens in harm’s way.

Now the window of opportunity for Western countries to truly help the Libyan people achieve their aims of security, justice, and the rule of law as pledged in Paris on 13 February is rapidly closing.

UK‘s pivotal role

The US, UK, and French embassies in Tripoli issued a joint statement on 8 May reiterating their support for Libya’s transition and their dismay at the use of violence. Yet such statements may seem to Libyans as ‘too little, too late’, because they fail to dispel fears of a Western exodus. As the security situation in Tripoli and Benghazi has deteriorated, expatriates in the oil sector and diplomats serving as advisers at Libyan Ministries have been forced to leave the country.

Even though the blockaded ministries reopened on 13 May, the foreign advisors are unlikely to come back any time soon. The French have promised to honour their commitment to send trainers for border security teams, but Britain occupies a pivotal diplomatic position able to reignite a new consensus for coordinated engagement in the country. Among world statesman, only David Cameron has both the inclination and the personal links to Barack Obama and the relevant Middle Eastern players (Turkey, UAE, and Qatar) to rally a new coalition to action.

Armed groups have shown their willingness and aptitude at interfering with democratic processes, while democratically elected bodies have shown tendencies to avoid violence and appease their armed opponents out of hope of building consensus. The scales are definitely tipping against the central government and it is truly impossible to say what will happen next.

Jason Pack is a researcher at Cambridge University, president of Libya-Analysis.com, and editor of The 2011 Libyan Uprisings and the Struggle for the Post-Qaddafi Future (Palgrave Macmillan June 2013).

[…] https://africanarguments.org/2013/06/06/in-libya-anarchy-reigns-and-international-engagement-is-sorel… […]