Collapsed, failed, criminalized? Notes on the State in Mali – By Isaline Bergamaschi

The crisis in Mali has certainly revealed some of the structural weaknesses and failures of the Malian state. Having experienced several waves of privatisation, the state is no longer seen as being a major provider of jobs or protection against the risks associated to climate conditions or the country’s fragile insertion into the global economy. Critics of the former regime led by Amadou Toumani Touré (ATT) pointed to the fact that democratisation in Mali had gone hand in hand with what Bayart, Hibou and Ellis called “˜the criminalisation of the state’.

Since the 1990s, successive governments were accused of distributing huge parcels of fertile land near the Office du Niger (an irrigated agricultural area near Ségou in south-central Mali) to international firms. Corruption scandals also came to light about the Global Fund to Fight AIDS Tuberculosis and Malaria. After a Boeing 727 carrying six tons of cocaine (coming from Latin America and transiting in the Sahel on its way to Europe) landed near Gao in November 2009, the president and his “˜clan’ were suspected of having connections with and protecting drug-traffickers by US authorities and the national press. The army’s lack of preparation, equipment and unity – despite several US-sponsored military programmes and training – were evidenced during a quasi-improvised coup and multiple insurgent attacks in the North between late 2011 and early 2013. The corruption of high-ranking generals – suspected of having “˜eaten’ the money and built spectacular houses for themselves in Bamako – was a central grievance of putschists and their supporters.

The crisis has challenged the status of Mali as a democratic success story and ‘donor darling’. Finally, popular support for France’s Opération Serval in the streets of Bamako and in the occupied cities of the North in early 2013 triggered legitimate perplexity about the meaning and practice of sovereignty in post-colonial Mali. With the deployment of a French military intervention and of the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (Minusma) on 1st July 2013, some Malians and analysts foresee the country’s future as one of “neo-trusteeship”.[1]

As the crisis mostly took them by surprise and challenged their assumptions, some of Mali’s donors are currently reflecting upon the efficiency of their past programmes of “˜capacity-building’ targeted at public administrations and, significantly, of budget support (aid funds delivered directly through the national Budget) and its follow-up mechanisms. For most aid workers, the crisis was a political one, but the sustainability of public policies must be guaranteed through and by the State and public administrations, which do exist and must be strengthened in the long-run. This vision contrasts with that of a number of humanitarian actors, i.e. NGOs and UN specialized agencies which deployed massively in the country from spring 2012 to tackle the political and food crisis.

For these organisations, which in some cases arrived in Northern Mali just when most administrations and public servants had fled violence to the South or neighbouring countries, the country’s current socio-economic situation is the result and indication of the past drawbacks and insufficiencies of international development assistance and the Malian state alike. For them, priority should be given to emergency relief for population in the short-term, through parallel implementation units and structures when necessary.

In brief, a lot has been said and debated about the Malian State in the past year and a half. This note provides a contribution to this crucial discussion. It argues that the state has a long history in Mali, which builds, in practical and symbolic terms, on the country’s rich imperial past; and that Mali can on no ground be described as an “ungoverned space”[2] or a case of “˜state failure’ – a notion coined in reference to the situation of Somalia in the early 1990s.

On the one hand, the crisis has triggered more demands towards the state than attacks against it. Despite its observed weaknesses and its borders – often described as “˜imposed’, inherited from colonialism and inappropriate to cultural identities, the nation’s unity, state sovereignty and territorial integrity have been the leitmotiv of public debate and political discourse. Whether one believes them or not, the putschists claimed that they had interfered into politics to “save the sate” and rescue the Republic from civilian mismanagement.

In late March 2012, the capture and imprisonment of several politicians widely regarded as corrupt initially earned Captain Sanogo and his crew of Green berets a certain degree of respectability. The only true challenger of the Malian state, the Tuareg-led Mouvement National for the Libération de l’Azawad, ironically fought for the creation of a state of their own. Countrywide, the restoration of order, morality and ethics in the state and in society were key features of the agendas of the military and the Islamists alike. In other words, Malians do not reject the idea or existence of the state, but rather ask for its re-founding according to higher aspirations regarding what a good state and politics ought to be.

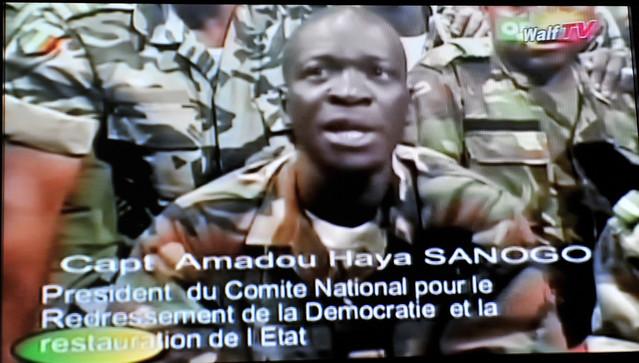

On the other hand, the Malian state has displayed a good deal of resilience and continuity in the midst of the crisis. Many offices and administrative buildings had been ransacked in the confusion and uprisings that followed the coup: it seems that the putchists and their supporters attacked public buildings as symbols of the former regime and were also looking for cash. But Captain Sanogo himself, after he took the lead of the putschists and established the Comité national pour le redressement de la démocratie et la restauration de l’Etat (CNRDR), counted on civil servants and the state. On the 24th of March 2012, only two days after the coup, he convened the Secrétaires généraux and/or directeurs généraux of all ministries for a talk in Kati. Some of the civil servants who were present that day recall that his key message was two-fold: a harsh criticism against ATT’s rule and an invitation to ensure the continuity and normal work of public administrations.

The civil servants, who confess that this encounter acted as a wake-up call (they realised the gravity and depth of the crisis), listened respectfully to this “son of the people” (the coup had not been fomented by hauts gradés, i.e. high-rank generals, but low and middle-rank soldiers) who was multiplying arrests. After bowing in front of the state elite, the Captain asked all state agents to go back to work. Those who would fail to do so would lose their job.

Despite all types of material obstacles (electricity cuts, pillaged offices, stolen computers and chairs, the lack of resources due to the suspension of most international aid), staff in the ministries did their best to function normally, collect information about the situation in the North and meet the population’s most urgent needs. The Ministry of Health and the centres de santé communautaires played an instrumental role in fighting the cholera outbreak over summer 2012.

Some institutional continuity could also be observed by the fact that salaries of civil servants have been paid and the state’s basic public spending (the dépenses de fonctionnement) have been ensured (at the expense of the dépenses d’investissement) all throughout this critical period. Finally, under military rule, civil servants did their best to avoid irrational public spending until the establishment of a civilian, transitional government in late April 2012.

Thanks to the systí¨me intégré des dépenses publiques, furthermore, the possibilities of public spending were quickly “˜locked’ and the junta was unable to sign Treasury cheques in the name of the state. The Minister of Finance, Tiena Coulibaly, is believed to have guaranteed strict spending discipline and overall budget balance in 2012-2013. He apparently refused to endorse a number of financial transactions on the grounds that they did not meet the normal budgetary and procurement procedures. Some believe that this is why he was sacked in June, just one month before the presidential election.

For all these reasons, the “˜failed state’ narrative does not fit the Malian state. As Minusma and other actors are about to engage in state-building activities, it is important that they keep in mind that the Malian state is not a vacuum to be filled or some alien project to be built from scratch. There is no need to reinvent the wheel: on the contrary, there is already a lot of material out there to build on.

Isaline Berganaschi is Assistant Professor at Universidad de los Andes and coordinator of a research project on the 2013 election in Mali. The project is led by the association Miseli and is composed of Prof. Johanna Siméant, Alexis Roy, Youssouf Sanogo, Julien Gavelle, Abdou Segou Ouologuem, Laure Traoré, Laurence Touré and Mahamadou Diawara. Field-work missions are funded by the French embassy (Service d’action culturelle et de coopération) to Mali.

[1] Guichaoua Yvan, “Mali: Towards a neo-trusteeship?” and “Mali: the fallacy of ungoverned spaces”, posts on Mats Utas’ blog: http://matsutas.wordpress.com/2013/02/14/mali-the-fallacy-of-ungoverned-spaces-by-yvan-guichaoua/

[2] For a critique of this “ungoverned space” narrative, see Clionadh Raleigh, Caitriona Dowd, “Governance and Conflict in the Sahel’s “˜Ungoverned Space’“, Stability: International Journal of Security and development, 2 (2), June 2013: http://www.stabilityjournal.org/article/view/sta.bs and Brachet Julien, « Sahara et Sahel : ni incontrí´lables, ni incontrí´lés“, Dossiers du CERI, July 2013: http://www.sciencespo.fr/ceri/fr/dossierceri

[…] Did coup-leader Captain Amadou Sanogo turn out to be the strongest defender of the Malian state?The crisis in Mali has certainly revealed some of the structural weaknesses and failures of the Malian state. […]

Thank you, your article is very informative and has widened my understanding of the issues in Mali from a different perspective. Mali like many countries including Ireland face unprecedented problems which had often been masked until pressure from problems reached a tipping point and everything fell apart. Ireland’s financial falling apart did not end in a physical coup but we have ended up with a double edged sword from our rescuers the IMF and others who now have more sovereign power in Ireland relative to our government. Well done Mali in fighting to hold onto your sovereignty, in building on a history of a strong state and trying to redress the corruption which had crept in and had undermined it. In Ireland we are still struggling to bring those responsible for our economic crisis in 2006 to justice. Going back to go forward is not easy and sometimes it is not even necessary if the right structures are put in place after the crisis point. I hope Mali manages to do that.

Teresa Comiskey