Historical Backlash or Contemporary Realities for Uganda’s Asian population? – By Georgia Cole

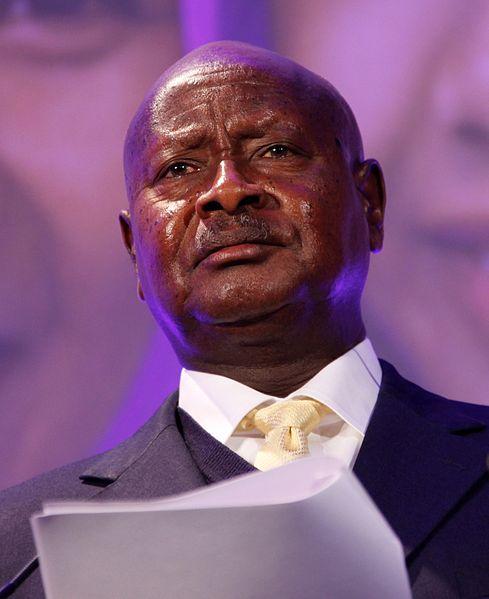

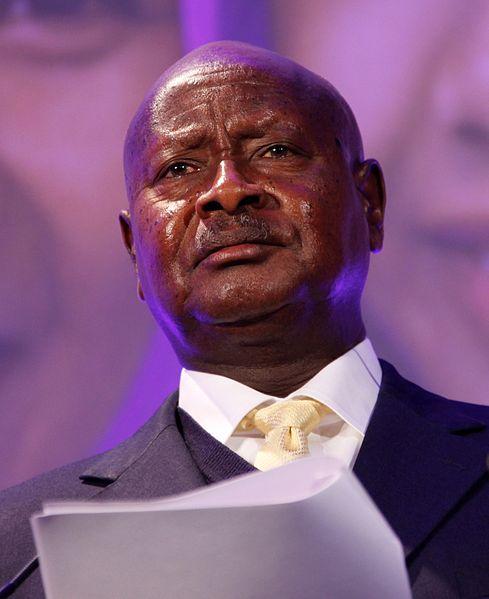

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has called continuing calls for expulsion of the country’s Asian population “the ghost of uninformed xenophobia.”

A recent incident in Uganda suggests that the state has once again failed to acknowledge and address the problem of anti-Asian sentiment on its streets. In October 2013, a Ugandan woman was allegedly gang-raped by a group of Pakistani men in an upmarket Kampala suburb. That the story received extensive media attention calling for a strengthened justice system was not surprising; the underlying focus of the public’s onslaught was, however, less expected and almost totally ignored. For example, whilst the caption describing the main photograph accompanying the story in one Ugandan daily newspaper read “˜rights activists hold placards…demanding the management to produce the remaining…people suspected to have gang-raped a 23-year-old girl,’ the banner displayed in the photograph clearly read “˜Foreign Investors: Stop Exploiting Ugandan workers now’.

2007 saw a similar incident of societal discontent boiling over in to anti-foreigner sentiments. The controversy focused on the give-away of the 7,100 hectares of the Mabira forest to a Ugandan-Indian owned company for the expansion of sugar cane production within the country. Though some explained the citizens’ riotous response as testimony to the population’s increasing environmental consciousness, others noted that “˜only the most undiscerning observer will fail to see that there were very powerful undertones in this riot that had nothing to do with loving trees’.[i] Though the riots lasted only a few hours, participants carried banners reading “˜Asians should go’ and “˜for one tree cut, five Indians dead’, whilst the mob spread out across the city looting Asian businesses and stoning an Indian man. When forced to acknowledge the xenophobic undertones of the rioting, the government was quick to dismiss its contemporary origins, blaming the violence instead on latent historical prejudices.

This antagonism, and other anti-Asian statements, has been dismissed as a product of the era of General Idi Amin. In 1972, the then president ordered the Asian population to leave Uganda under the pretence that “˜they only milked the cow but did not feed it to yield more milk’. They were given ninety days to leave the country, and legally prohibited from selling their properties and businesses before they departed. Their expulsion was seen as a necessary step to facilitate the “˜Africanisation’ of Uganda, as wealth and power were considered to be disproportionately owned by the country’s non-indigenous population, the majority of whom were of Indian descent.

Even a cursory analysis of Ugandan politics, however, suggests that this recent spate of anti-foreigner sentiment, including calls for their expulsion, does not have its roots in what President Yoweri Museveni has called the “ghost of uninformed xenophobia.” From an immigration policy perspective, it instead shows a clear failure to adequately consider the return of those forced to leave the country in 1972, along with poor implementation of contemporary policies designed to encourage a flow of foreign investors to the country.

Firstly, the return of those expelled by General Amin was completed in a fashion illustrative of both amnesia and myopia. Under immense international pressure, including withholding international loans, the government of Uganda formed the Departed Asians Property Custodian Board. The board was tasked with courting Indian investors to return to either reclaim their properties and businesses, or receive compensation for their expulsion. Although President Museveni and several prominent Asians argued that this return process would simply reposition Asians as a privileged class vis-í -vis local populations, there was little room for any alternative policy decisions, as international backers considered this the most expedient way to recover the economy. This return movement, which occurred simultaneously with a huge state divestiture program, repositioned Asians in the upper classes whilst critical issues of meaningful reintegration and indigenous economic development were overlooked.

The government has made no secret of the fact that these foreign investors were and are seen as a panacea for domestic development, with Indian construction, manufacturing and production firms playing a huge role in Uganda’s economic development. The ruling National Resistance Movement has persistently encouraged Indian investors, seeing them as essential to Uganda’s global economic integration, and some have suggested that investment regulations may not have been strictly adhered to. Along with the malaise arising from preferential treatment towards this group of investors, the absence of any serious wage regulation in Uganda has left the huge number of workers employed by these investors feeling mistreated and exploited.

Secondly, the government has failed to understand or respond to the continuing resentment of the country’s Asian population. Many feel either exploited in their factories or undercut on the streets. The self-confessed failure of the Immigration Department to limit the arrival of general employee visa category immigrants, despite existing regulations which state that visas can only be handed to those filling positions to which no Ugandan is suitable, has been a recurrent disappointment to petty traders and retailers. This group feels marginalized by Indian shop owners, with their strong trade connections enabling them to import products cheaply from India. Over 80 per cent of Indians entering Uganda come as general employees, putting them in direct competition with low-skilled Ugandans. The paucity of immigration, investment and import regulations has left Ugandans feeling severely disadvantaged compared to a population of old and new Indians migrants with a highly visible and clearly successful public presence.

There is no doubt that the 2007 riots and ongoing anti-Asian sentiment within the population have a broader relationship to Uganda’s current political economy which stretches beyond the realm of immigration. It nonetheless appears that historical and contemporary mismanagement of migration in the region has contributed towards the current situation in Uganda. Those expelled in the 1970s were welcomed back without attempts to mitigate the imbalances which originally inspired forced extradition. In January 1972, months before their expulsion, Indians submitted their Second Memorandum to General Amin urging changes to a system which they recognised facilitated their disproportionate success, in the hope that this would lead to African business development. In 2007, prominent Indians repeated this plea, arguing that the government’s labelling Indians as investors, rather than nationals or Ugandans, institutionalises their preferential position and solidifies their distance from native Ugandans.

This has perpetuated a view within Ugandan society which supports General Amin’s ideological premise for expelling the Asians from the country – many voices suggesting that it was the “˜right idea, at the wrong time’. The placards and violence were and are, however, intimately tied to the failure of the government of Uganda to sensitively reintegrate a large community of returnee Asians following their forced migration from the country, and their continuing inability to adequately manage the thousands of immigrants entering the Ugandan economy every year.

The government is wrong to blame the rising anti-foreigner sentiment of its citizens on prejudices inherited blindly from the rhetoric of General Amin. Such emotions reflect a reintegration policy of the 1990s which was blind to its societal ramifications, and a pattern of contemporary immigration which has left the population questioning whether its government has learned any lessons from its past mistakes.

Georgia Cole is a researcher in the Department of International Development, Oxford University.

[i] Busharizi, P. (2007) “˜Mabira Demo Revealed our Envy’ New Vision, 16th April