How tribalism continues to direct governance in Sudan – By Namaa Al-Mahdi

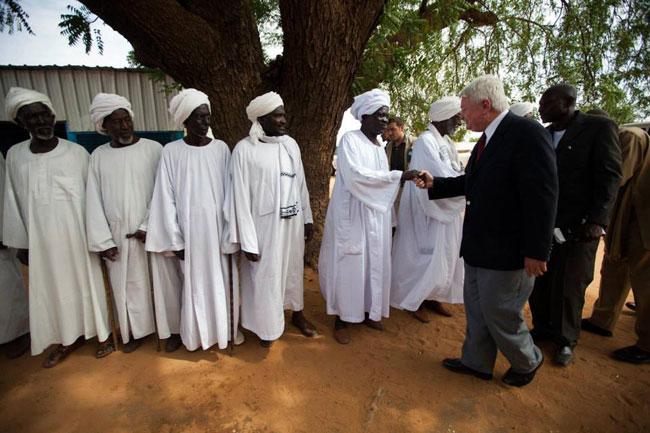

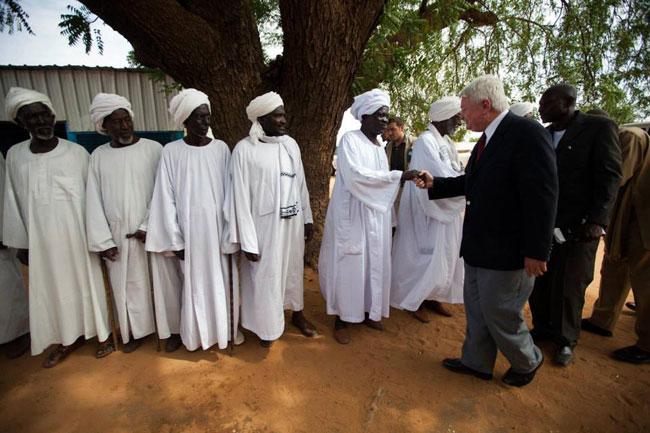

UN Peacekeeping chief Ladsous meets leaders of the Rezeigat tribe in El Daein, East Darfur. The Rezeigat have been involved in recent violence with the Ma’alya. (UN Photo/Albert González Farran.)

Tribal clashes between Ma’alya and Rizeigat tribes broke out in early January of this year, multiple clashes throughout the year culminated in an all-out war last August in the oil rich State of East Darfur, leaving scores dead and injured from both tribes.

Conflict between the two neighbouring tribes over rights to land, shared resources and leadership has spanned several decades, the last two years has seen an upsurge in conflict between the two tribes, which left thousands dead and hundreds injured. The peace agreement which was signed by tribal chiefs and elders last September 2013 was broken, on the 14th of this month; the government announced an open ended state of emergency, a 7am-6pm Curfew and a ban on carrying weapons in and around the capital of East Darfur- Ed-Daein, the centre of the Rizeigat tribe’s leadership.

The announcement of the curfew followed a serious attack by Rizeigat tribesmen on a senior army official, following their discovery of a train load of weapons heading from Nyala in North Darfur to Adeelah, the Ma’alya’s centre in East Darfur. The Sudanese Armed Forces, official spokesperson, Swarmi Khlaid Saad, denied any involvement in the incident as well as the distribution of arms amongst the tribes.

In January 2013, unreported[ii] conflict between two clans of the Messiryah tribe in Al-Fula village in South Kordofan State left 80 dead.

“The current upsurge in intertribal conflict is backed by the government to distract the tribes from making claims for their share of the oil coming out of their lands, residents of Al- Fula say they are desperately poor whilst their land’s wealth is making the government rich” says ex-Colonel Fadallah Burmah Nasser who acted in the capacity of the Ansar Affairs Committee mediator between the conflict parties in Al-Fula in South Kordofan.

The regions of the current upsurge in tribal conflict are located within oil block 6; according to Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company (GNPOC) the block produces 44,000 barrels of oil a day, and is controlled by a consortium led by China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), oil block 6 stretches across the border between South Kordofan and East Darfur State.

The Sudanese ruling party’s heightened interest in South Kordofan’s and Darfur’s recently discovered oil fields and its role in spurring violence in the area fits an ongoing pattern of setting neighbouring tribes against one another to consolidate economic control and power. A well-known strategy of “divide and rule” works by governmental favouritism of the smallest tribe in any region, active support and militarization of these tribes to create a power imbalance in favour of the tribes with the smallest numbers.

The pattern of results has always been heightened antagonism between the government backed tribes and the traditional leadership, a position traditionally held by the biggest tribe in the region- inter-tribal disputes sometimes start off between the youth of the tribes, often leading to deadly conflict.

Reuters, Enough! and Satellite Sentinel Project, published reports on the fighting between government backed Aballa (camel herders) militia and the Bani Hussein in North Darfur over gold rich Jebel Amer- belonging to the Bani Hussein, conflict led to the burning of 150 villages and displacement of over 150,000 people in the early months of 2013.

Whether the issue is the control of resources or the suppression of rebellion against the government, such as the use of Rizeigat Janjweed militias from the Mahameed clan against the Zhagwa led rebellion in Darfur 2003 and the current conflict in the Nuba Mountains, which started in June 2011 with a government backed Messiryah tribesmen’s attack on the largely Nuba based Sudanese Peoples Liberation Movement/ North (SPLM-N), the government has turned tribe against tribe in the Sudan to expand its control and re-affirm its iron fist hold of the country.

Tribalism is at the heart of Sudanese culture; it informs and guides the nation’s moral compass and set of values and practices. One of the first pieces of information exchanged between two newly acquainted Sudanese revolves around tribe. The tribal set of values are transferred from parent to child in the family, they are embraced and practiced in the neighbourhood, at school, in social groups, at the work place and in the whole community. On a grander scale, these values constitute the mental program of the nation.

Tribal values are an integral part of the Sudanese people’s collective relationship with authority, power and governance.

Tribal structures provide social, economic and financial support to members and a much needed safety net for families when the State, which is largely absent from the lives of many, fails to do so.

In urban settings, Sudanese who moved into multi-tribal cities such as Khartoum and Omdurman moved as tribal units and maintained their tribal integrity within the city. The old part of the city of Omdurman is stratified along tribal or extended family lines. At the heart of the city by the market, are the Robatab, the Omrab (a sub-section of the Jaliya tribe), the Ghandeer, and the Copts. Further on towards al-Abasyia reside the post-Mahdiya families- a homogeneous mix of tribes of Darfur and the Nuba Mountains, neighbouring them are the post-colonial civil servants’ families who make up Hai al- Doubat, then the Hashmab family. Further afield in al- Mourada are the Mahas and in Wad Noubawi live the Danagla.

Social dominance and hierarchies in the Sudan are thus determined by tribal structures. Often, these hierarchies have a distinct authoritative leadership. The tribal hierarchical structures coerce members of the tribe to uphold the cultural and socio-economic order, acting like a mini-state – but whose mechanisms only benefit a select group connected by kinship.

At the top of the tribal hierarchical structure, sits the chiefs- in cities the position is taken by a family elder- they wield absolute authority over their group. In exchange they have the responsibility to house, feed, educate and employ tribal members as well as settle feuds and act as mediators during conflict. The tribal chief’s home is often used as a venue for tribal members’ social occasions and for hosting visitors to the area.

Tribal chiefs and elders steer their members’ political affiliations, choice of religion, and even have a role in personal choices such as who to marry and when. The tribe acts as a collective.

After independence in 1956, graduates of the three main secondary schools, Khor Tagat, Wadi Sayidna and Hantoob went on to create the bulk of a relatively modern middle income class, semi-nuclear families and formed the modern political parties, the Sudanese Communist Party, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Ba’ath Arab Socialist Party.

But did the educated elite who created these political parties eschew the tribal-ness of the society around them?

The evidence suggests otherwise.

Instead of working on building a nation-state that strives for equality in the distribution of wealth and opportunities through a social welfare system paid for by taxation, political parties have adopted the tribal system of leadership within their party structures.

Political activities function around the provision of tribal style support to members and a great deal of time and effort is invested in tribal support systems such as the strengthening inter-personal and family based relationships rather than focusing on building effective political party systems or government administration institutions.

The tribal function of social support and protection to a select group was transferred from tribe to political party and consequently to the State when these political parties take power.

At the very core of tribalism, lays a system whereby the group relies on the tribal leader and elder to provide financial, social and economic support in a similar manner that a father figure would, in exchange for absolute loyalty and obedience. This is how Sudan is governed.

Many in Sudan see their political party leader as their tribal sheikh or father figure. Many political party members are as loyal to their leaders as they would be to their own parents. Therefore criticism is usually personal based on their failed duty as parents/guardians and not based on their actual “job-description” as political party leaders.

Most of the current political parties do not have coherent constitutions and or a set of policies aligned to their identity. Political membership is purely based on the relationship with the party leader and in response to his/her charisma.

As a result, party members have various assumptions about the expected role of a party leader. The assumption is mainly based on the role of a tribal leader rather than a political party leader who is proposing a manifesto to run a modern State.

In this tribalised scenario, party leaders who fall short of the authoritative/care provision tribal leadership role, are branded as failed politicians. In contrast, party leaders who use their influence to broker business deals for party members and to facilitate access to higher education and jobs as well as broker marriage deals are considered successful politicians.

Namaa Al-Mahdi is a human rights campaigner and political activist, She is reachable at [email protected] or @namaa0009