Home Sweet Home: Kabila’s troubled relationship with Katanga – By Kris Berwouts

Since the beginning of 2014, electoral fever in the DRC has been on the rise, although presidential elections aren’t scheduled before the end of 2016. Joseph Kabila is in the middle of his second and constitutionally his last mandate as president of the Third Republic. In January 2001, in the middle of the war, he succeeded his father who had been assassinated by a body guard in his own palace.

Since the beginning of 2014, electoral fever in the DRC has been on the rise, although presidential elections aren’t scheduled before the end of 2016. Joseph Kabila is in the middle of his second and constitutionally his last mandate as president of the Third Republic. In January 2001, in the middle of the war, he succeeded his father who had been assassinated by a body guard in his own palace.

Kabila remained Head of State during the transition which started in 2003. He won the elections in 2006 and was sworn in as the first president of the Third Republic, which Congolese and international observers declared were free and fair.

In November 2011, he was re-elected. This time, the elections were much more closely contested and his main challenger, Etienne Tshisekedi, has never accepted his defeat. In the last few months the political scene in Congo has become obsessed by Kabila’s plans for 2016. Will he stay or will he go?

Rich

At this moment it looks rather unlikely that Kabila will find a consensus in his own camp to remain in power. The reticence starts in his home province of Katanga. Via his father, Kabila is member of the Balubakat community – the Baluba from North Katanga. Both Kabila regimes (pí¨re and fils) are perceived in Congo as a Swahili-speaking Katanga-based fortress.

Katanga is a complex province, rich in minerals and much more industrialized than the rest of the country. However, Katanga doesn’t exhibit development indicators above the national average, largely because there are enormous discrepancies between its territories and districts.

The north of the province, where the Balubakat come from, has been largely absent of the growth dynamics observable in the major cities, such as Lubumbashi, Likasi and Kolwezi. The people there blame their own leaders for this: Balubakat leaders have been well-positioned since Laurent-Désiré Kabila took power. They enriched themselves very visibly but there has been hardly any return for North Katanga.

Most politicians in Congolese history have used their mandate to develop their region by rehabilitating roads, building schools and hospitals etc. The population of northern Katanga and especially the Balubakat community accuses its leaders of neglect their own people.

Self-declared prophet

The fact that Kabila had a problem with his own community was made dramatically clear just before New Year 2014. On the morning of December 30th, lightly armed people entered the buildings of the RTNC (Radio et Television Nationale Congolaise) and similar attacks took place elsewhere in Kinshasa: around the military camp Tshatshi and at Ndjili International Airport. The police was able to take control of the situation very quickly.

Eventually, the attackers were identified as followers of a religious leader claiming to be the “˜Prophet of the Eternal’, Paul Joseph Mukungubila – a former, if rather unsuccessful presidential candidate, (59,228 votes in 2006) who preached a bizarre mix of anti-Kabila and anti-Tutsi rhetoric.Earlier in 2013, three senior Balubakat leaders had lost national responsibilities: John Numbi, Jean-Claude Masangu and Daniel Mulunda Ngoy.

The incident happened only two days after the official confirmation of Charles Bisengimana as Chief of the National Police. Bisengimana, a Tutsi who was part of the rebellion of Laurent Kabila in 1996-1997, had been acting Chief since General John Numbi was suspended due to his possible involvement in the assassination of senior human rights activist Floribert Chebeya in June 2010. Until Chebeya’s death, Numbi had been one of the strongmen in Kabila’s inner circle.

In May 2013, Jean-Claude Masangu ended his last mandate as president of the Congolese Central Bank (Bececo). He was replaced by Deo Gratias Mutombo, a Bececo technocrat from Katanga, but non-Mulubakat.

In June 2013, Daniel Mulunda Ngoy had to leave the presidency of the CENI (the Independent National Electoral Commission) because he was held responsible for the contested elections of November 2011 and the damage done in terms of loss of legitimacy and stability for the regime. He was replaced by the catholic priest Apollinaire Malumalu, who previously led the commission which had organised the historical elections in 2006.

Even today it is very difficult to understand exactly what happened and why. The government has done its best to reduce the incident and its relevance to the Prophet’s narrative and present it as an isolated action of religious zealots. But Congo is a country with an outspoken taste for rumour and conspiracy theories. Even before the incident was over, it had been called a coup attempt with much speculation about who exactly within the political or military elite was behind it.

It is important to see the actions of a Katangan prophet and his followers in the context of a powerful Katanga worried about losing influence in Congo. The prophet’s march was not a coup attempt but rather a sign that Katanga is not reassured that Kabila is serving its interests well.

Bakata Katanga

The most violent manifestation of Balubakat discontentment at grass-roots level is the existence of an armed group known as “˜Bakata Katanga’ led by Mai Mai leader Gédéon Kyungu Mutanga. They have been responsible for massive human rights violations in what is known as the “˜Triangle of Death’, the area between Pweto, Manono and Mitwaba where they destroyed villages and symbols of the Congolese state, which resulted in the displacement of hundreds of thousands of individuals.

The armed group is rooted in the secessionist history of the province. In fact, Bakata Katanga means “˜Cutters of Katanga’. Congo had its first implosion less than two weeks after independence, when the Katangan governor Moí¯se Tshombe unilaterally declared the independence of his province on July 11th, 1960 – inspired and supported by the western (particularly Belgian) industrial interest groups. The Congolese government and army were able to reunite the country three years later with the help of UN troops. Since then, the secessionist undercurrent remained present in the heart of many Katangans in all social strata of the province.

The Bakata Katanga are fed from below by the anger and the feeling of exclusion from rural communities. But, rather than being a spontaneous outburst of frustration, the movement is believed to be a construction, initiated by people around Kabila.

There had previously been Mai Mai activities in North Katanga as a form of popular resistance against the occupation of eastern Congo by Rwandan troops. Many sources have confirmed that in the period leading up to the 2011 elections, Balubakat in Kabila’s inner circle took the initiative to reorganize the remaining Mai Mai groups under a new umbrella.

Gédéon, one of the leaders of the first wave of Mai Mai groups in North Katanga, was placed in prison, sentenced to death for crimes against humanity during the war. In September 2011, he escaped to take the leadership of the Bakata Katanga. It is often stated that John Numbi and Jean-Claude Masangu were the people who created Bakata Katanga as a B plan to fall back on in the event Kabila lost the elections against Tshisekedi.

The development of the Bakata Katanga is in many aspects comparable to what happened with other armed groups in Kivu: it can exist because the people in the villages are frustrated and don’t feel protected by the state; provincial and national politicians try to structure and steer it but lose their grip after a while because the armed group very soon starts to interact within very local dynamics and escapes from all forms of control. This Includes the control of its own commanders: at this moment, the Bakata Katanga cannot be considered a coherent organization with clear lines of command.

On March 23rd 2013, a group of Bakata Katanga fighters, many of them women and children armed with machetes and bows and arrows and covered with charms and amulets, marched up to Lubumbashi and raised the old flag of independent Katanga in the city’s main square. After a battle with security forces that killed 35 people, the militants forced their way into a UN compound where 245 of them surrendered.

After that incident, the military operations of the Congolese army against the Bakata Katanga intensified and managed to considerably weaken the armed group. This does not necessarily mean that the security situation improved: the operations have dispersed the Bakata Katanga in the Triangle of Death, driving them further south in the direction of Lubumbashi and the Kundelungu and Upemba national parks. The pressure on Lubumbashi increased and fears of a rebel attack on the city are running rampant.

Decentralisation and découpage

The traditional tensions between North and South Katanga are related to the decentralization process and more particularly the découpage. The constitution of the Third Republic defines Congo as a federal state where the provinces have political, fiscal and juridical autonomy and important responsibilities in the organisation of public life. To enable them this, the Constitution stipulates that the provinces are entitled to use 40% of the national taxes raised.

The aim of decentralization is to reinforce good governance and accountability, improve the administrative efficiency and increase the democratic participation of the citizens. It is difficult to be against that, especially in a province where people tend to think that most of the problems are imposed by the capital.

But the Constitution also foresees the splitting of the existing 11 provinces in to 26 smaller ones. This new territorial structure will be problematic in many places in Congo, because new balances will have to be sought, not only in terms of identity and ethnicity, but also regarding economic interests.

The Katanga case will be particularly sensitive. Dissolving Katanga into the four new provinces of Haut-Katanga, Haut-Lomami, Tanganika and Luluaba will exacerbate the division between richer and economically unviable parts of present-day Katanga. The mining history of the province led to complex patterns within the province and from elsewhere, for instance neighbouring Kasai. This has caused tensions and waves of violence in the past between communities on ethnic lines but with socio-economic root causes.

Balubakat in leading positions in Lubumbashi or Kinshasa, in control of lucrative economic activities (mining, transport, trade…) would be reduced to foreigners in the south of Katanga and cut off from an important part of their profits. The découpage of Katanga is potentially explosive and there is a lot of pressure to avoid its implementation.

Elite

Everywhere in Congo, Kabila’s regime is considered as Katangan, except in Katanga. For North Katanga, he is the lost son who has forgotten to take care of his family. For South Katanga, he is the incarnation of problems at the national level; extracting the wealth of the province without any added value in return.

Currently the tensions between North and South Katanga remain mostly under the surface because Moí¯se Katumbi, governor of Katanga since March 2007, has managed to mobilise a lot of support. He has introduced a new dynamic in the provincial capital of Lubumbashi and in other parts of the province, and his charisma seems to work far beyond the borders of his own community (from his mother’s side, he is a Bemba from South Katanga) and his region.

The charisma even works beyond Katanga. At a moment where everybody is obsessed by Kabila’s intentions regarding the elections in 2016, one of the main questions is: where will change come from in case Kabila decides or is forced to leave. It is very difficult to imagine that the opposition will defeat the regime by elections in a country such as Congo. It is much more likely that the initial drive for change will come from that part of the establishment which believes that its long term stability and interests are not served by eternalizing Kabila’s reign. In that case, it is quite possible that the present schemes of majority and opposition will be broken up to redraw the political landscape and give way to new alliances.

Many people I spoke with in Katanga and in Kinshasa, within the majority as well as in the opposition, look at Katumbi as the man with the best cards to make such a bid. He has an aura of a successful businessman and manager, as well as being an excellent organizer. He is known to be generous and able to bring people together. He also has the money and the looks to mount a great campaign.

Of course Katumbi has some important disadvantages: there is no doubt that his white origins (his father was a Sephardic Jew from the island of Rhodes) will be used against him. There are some dark shades hanging over his business past and the way he gathered his wealth. And in economic terms, he is a glutton: he uses his political position to expand his commercial empire. He lacks a solid intellectual background, although nobody remembers the last time that would have been a decisive criterion for the presidency…

At this moment, Katumbi is absent: he left Katanga early October for a cure to detoxify his body from the traces of an earlier attempt to poison him. Two months later, he still did not return and this again fueled rumours and speculations. So far, Katumbi has not yet made clear his ambitions for 2016.

A subject of significant speculation is his relationship with the presidential family. Katumbi leads the PPRD in the province but there has been a lot of distrust between him and the president in the past. Sources confirm that there has been a certain rapprochement lately. A move by Katumbi to the national level at some stage may not be incompatible with the Kabila clan, since the president’s younger brother Zoe, member of the senate since 2011, allegedly has ambitions to become governor of Katanga himself.

And let us not forget the grumbling man in the background of course. Congo got its government of national cohesion earlier this week and in September, the army top brass were also reshuffled. Both exercises gave Katanga no reason to complain, but John Numbi is still sidelined. He spends most of his time in Katanga and is very active in business. He runs his farm, an enterprise for road construction and a security firm. He doesn’t seem very influential in the main decision making circuits of the country but he is definitely on speaking terms with the president. And he wants to be rehabilitated. He is feared in the province and the country because nobody really knows how much loyalty he can still count on in the armed forces, including Kabila’s own Garde Républicaine.

Congo seems to need Katanga more than Katanga needs Congo and its leaders are well represented in the key positions of state.

Kris Berwouts has worked 25 years for different Belgian and international NGOs focused on building peace, reconciliation, security and democratic processes. He now works as an independent expert on Central Africa. He is currently writing a book on the conflicts in eastern Congo to be published in 2015 by ZED Books. He receives support from the Pascal Decroos Fund for Investigative Journalism for his field research.

Executive Breach of The Social Contract entailing a breakdown in Fiduciary Responsibility to the Citizens of DRC

Many emerging democratic societies suffer from the ‘lack of accountability to the citizen syndrome’. This syndrome can be further categorized as ‘the preservation of power syndrome’ regardless of constitutional or other civic civil constraint.

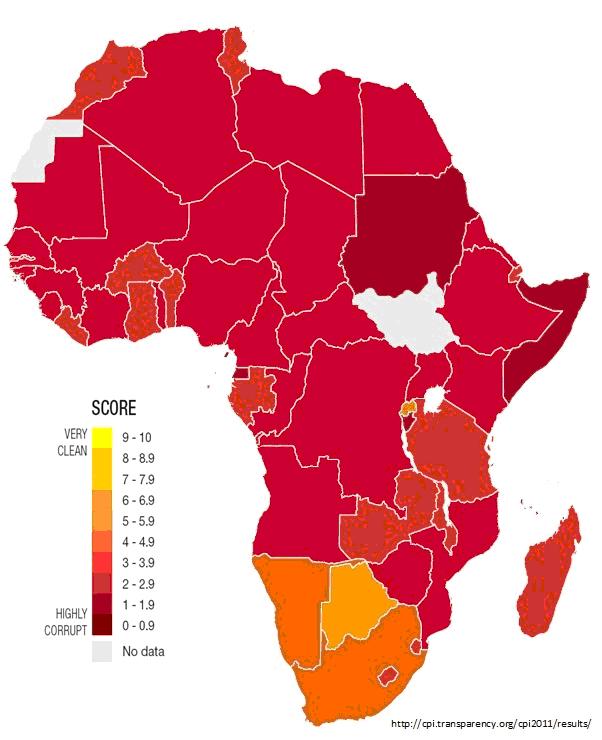

Unfortunately, this syndrome is most prevalent in fragile, weak emerging democratic societies governed by an egoistic oligarchy who utterly fail to respect the rule of law in public administrative governance practice.

My comment question is simple;—Does Executive non-compliance to the [already agreed upon] Constitution create a [fundamental] breach within the ‘social contract’—thereby affording natural law sanction to the Citizen right to civil civic protest redress?

Does failure by an Executive to hold an election on a date/year already agreed as witnessed in an open accordance in a prior agreement [articulated and embedded within the national constitution] constitute a fundamental ordinal breach in the civil social contract existing between those who exercise authority vested by the constitution and the citizen?

If a breach in the social contract between the Executive and the Citizen has occurred—what are the rights and privileges afforded to the Citizen to take action in a manner responsible and non-violent?

Furthermore, ought the International Community of Nations express displeasure to the offending Nation State over this fundamental breach of the social contract?

Many thanks for the Analyze of Congolese situation, so I believe the grand key or the corn stone of stability is based in Economic, and security so the” Detribalization” of all Institutions, religious, Civil and Military Administration is required to win the challenge of Decentralization and Découpage to reinforce good governance and accountability it is a process .

Sincerely, best Regards.