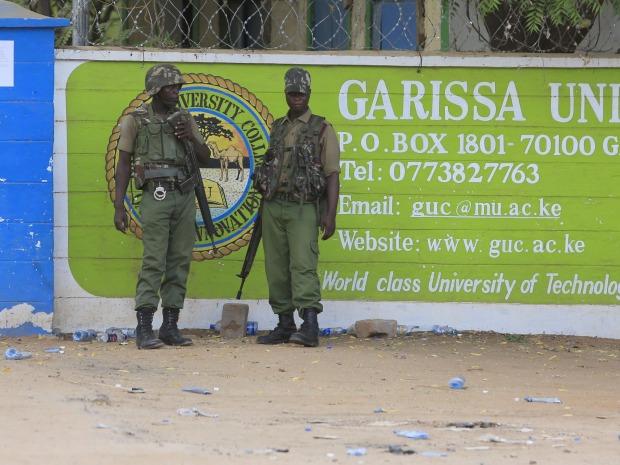

Kenya must better respect its Somali population to avoid another Garissa – By Mohamed Mubarak

On 1 April, Al-Shabaab gunmen attacked Garissa University College killing 147 Muslims and non-Muslim students alike. The gunmen attempted a feeble show of doing a religious test; but it’s inaccurate to claim that all those killed were Christians.

On 1 April, Al-Shabaab gunmen attacked Garissa University College killing 147 Muslims and non-Muslim students alike. The gunmen attempted a feeble show of doing a religious test; but it’s inaccurate to claim that all those killed were Christians.

The events that took place in Garissa were also inaccurately portrayed by local and Western journalists, who initially and recklessly referred to the gunmen as “Somali militants.” This made it seem like the group was made up of only Somali nationals or it represented the interests of the Somali nation.

One of the attackers has now been identified as being from northeast Kenya. Let me repeat that: he was from Kenya, not Somalia. None of the attackers has been identified as being from Somalia.

Journalists focused on the who (and didn’t even do a good job in answering that question) rather on why youth in Kenya are turning to extremism.

Al-Shabaab in Kenya

During the Ethiopian occupation of south and central Somalia from 2006-09, Kenya was used as a sort of rear base by many of the groups then resisting the Ethiopian occupation. Kenyan hospitals were used to treat some injured fighters from groups such as the Ras Kamboni Brigades, the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, and Al-Shabaab. Funds were raised and fighters recruited. The Kenyan government did nothing to stop all of this until 2009 when Al-Shabaab controlled almost all the areas of Somalia bordering Kenya.

By then many of the fighters from the other groups had been integrated into Al-Shabaab. It continued to raise funds and recruit from within Kenya.

The Kenyan government invaded Somalia in 2011 with the intention of installing a friendly administration along its borders in response to several attacks and abductions that had taken place in its Coast Province, most notably in the tourist destination, Lamu (it should be noted that these were not directly linked with the Somali insurgents).

There is no evidence to suggest that Al-Shabab would have attacked Kenya before the latter sent its troops across the border. However, in fairness to Kenya, Al-Shabaab is hardly a reliable security partner.

The major problem with the Kenyan intervention was that it failed to take into account the effects it would have on its own internal security. It had no convincing plan to simultaneously take care of security threats within Kenya whilst its troops were engaged on the other side of the border.

At this point the Kenyan security services came up with the policy of killing off Islamic clerics and the disappearing of hundreds of Muslim youth (reportedly murdered by security forces, according to an Al-Jazeera documentary).

Another problem for Kenya was the fact that its army expected to be welcomed as victors by a local Somali population that felt nothing but distrust for foreign armies marching into its territory. The indiscriminate aerial and naval bombings did nothing to win hearts and minds (quite the opposite). The policy of revenge bombings of Somali villages following Al-Shabaab attacks inside Kenya continues.

Al-Shabaab portrayed the Garissa attack as revenge for all the Muslim people killed by Kenyan troops in Somalia and Kenya; furthermore, it referred to the university as a place where Muslim youth were being taught “˜unislamic’ subjects. However preposterous this justification may be, its core audience seems satisfied.

On hearing of the attack, the most common response I heard from Somalis was surprise that the local Somalis in Garissa seemed to be the minority at a university in their own region. This fact was publicised among extremist circles to further justify the attack.

Aftermath

Following the attack, Somalis on Twitter could be seen expressing fears of going out to donate blood lest they be harassed by Kenyan troops. Many were reportedly beaten by the security forces, which would strike most people as being an ineffective method of defeating an insurgent group.

But, as Richard Dowden rightly notes, Kenyan troops have been doing this to the Somalis since independence. Thousands have been killed in Wajir and Garissa by troops who, ironically, claim that they are deployed to stop inter-clan killings among the Somalis.

On Mohamed Adow’s documentary for Al-Jazeera, Not Yet Kenyan, one of the interviewees tells him that on one day in the early 1980s the Kenyan troops raped “every woman in Garissa”. Let me repeat this for you: Kenyan troops raped every woman in Garissa in one day in the early 80s.

Whether or not all were actually raped is irrelevant; what matters is the perception among the locals that all their women were at one point violated by Kenyan troops.

In Nairobi, as recently as a year ago, more than a thousand ethnic Somalis were rounded up by Kenyan security forces and kept in open air cages that were caught on film by a human rights activist. For months these people, many holding Kenyan citizenship, were kept in squalid conditions, with at least one woman reportedly giving birth without any medical help from her Kenyan captors.

If we want to discuss why Kenyan youth from communities that have been oppressed by the state join Al-Shabaab, there you have it. Kenya needs to treat its citizens equally and stop pointing the finger towards the border.

Mohamed Mubarak, a political and security analyst, is the founder of anti-corruption NGO Marqaati (Marqaati.org), based in Mogadishu @somalianalyst

We always told them that ,unless we enjoy the resources and opportunities equally with other kenyans,we shall remain second class citizen.We mourned for 31 years, no one cared.Fellings can’t be regulated.Security heads in Kenya are all non-Somalis.Blame money takers gready Kamaus, Musyoka,OleOle, Tanui of this world.#CORRUPTION in kenya is killing

Provocative. The Kenyan government has no history of respecting most ethnic groups in Kenya. Fact. however, disgruntled members of the 40+ ethnic groups haven’t resorted to murdering their fellow countrymen and innocents in neighbouring countries in cold blood to make their point. And yes, alshabab DID provoke Kenya before the “invasion” if you choose to conveniently ignore the fact that Somalia was well at war with itself for over 2decades without Kenyan intervention- even under pressure from global superpowers, then you should peddle your ‘opinions’ somewhere other than the Internet, where people are likely to expose your blatant revisionism.

I will tell you what you are- you are an unashamed Islamist terrorist sympathiser who thinks that by repeating a lie about a manufactured Kenyan agression, that you can avoid the harsh questions that Muslims must ask themselves today- why and how their communities continue to Produce such mindless bloodshed, illiberality, intolerance, barbarity and human suffering generation after generation.They need to talk more about how they’re going to fix it, not whine and complain and blackmail everyone with threats of more violence unless they get what they started the aggression for. This simply won’t do, and we are getting tired of hearing it. Africans suffer equally under ineffectual leaders but behaviour such as seen from alshabab boko haram etc etc ad nauseum springs mainly out of Muslim communities, with hardly a murmur from the so called umma- why you get more outrage for a mere cartoon than for the endless Flow of blood effected in the name of your God and religion.Spare us the manufactured Islamic outrage and learn to live with your neighbours.people can protest state excesses without abducting and raping schoolgirls or blowing children up in buses and churches!people can influence change in their societies without singling out nonmuslims for cold blooded murder or burning down churches in Africa because of cartoons drawn in Europe! and people most certainly can rebuild their own country without tearing down another or attempting to impose barbaric legal codes on those who don’t want it!

Now that you are all but promising more of such attacks Unless your blackmail demand is delivered, (as if I haven’t encountered this heinous tactic before!)how can you possibly present yourself as a voice for the solution? Better use of your time would be to have a word with these crazed and hopeless people( for that is what they are, crazy with hopelessness and trapped in a religious outlook not fit for this century)not arming them with a dubious moral excuse to launch yet more suffering on poor people.

And African arguments can do better than present such nonsense as an opinion to discerning readers!

The author of this article is heavily biased. However, I believe it is time Kenya woke up to the threat of ethnic somalis. All the 40-something tribes in Kenya suffer because of ineffectual leaders but only Somalis resort to indiscriminate murder to show their frustration. Kenyans are very peaceful people and welcoming to outsiders.

I fully support the eviction of refugees from Daadab and I’m hoping that the Kenyan government will proceed to evict all Somali refugees from Kenya. We already have enough problems to deal with as a country and Somalis are compounding to the problem.

I do hope that Somalia can sort out its issues so that the Somali people can return to their land.

You only need to watch the Sex Slaves of al-Shabab on Our World, on the BBC News channel to know that they aren’t any better than the Kenyan troups of the 1980s.