Xenophobia Vs Pan-Africanism: Is This How South Africa Remembers Tanzania’s Hashim Mbita? – By Chambi Chachage

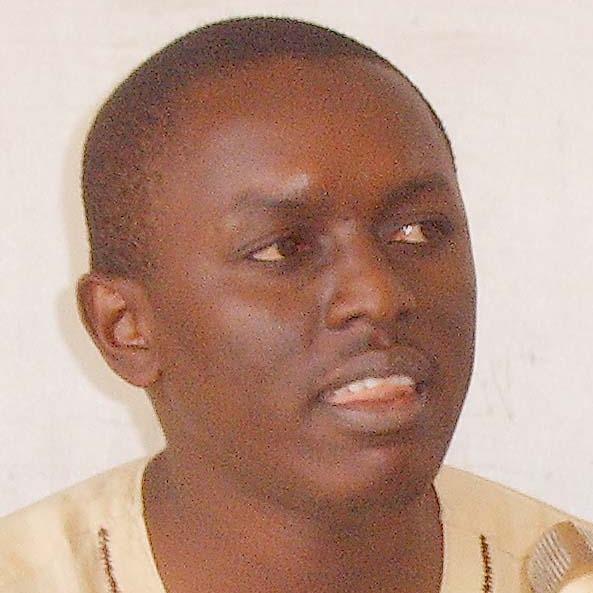

I wonder what went on in Hashim Mbita’s mind as he breathed his last on 26 April 2015. What did the Retired Brigadier-General think of the xenophobic attacks in South Africa? As the former Executive Secretary of the then Liberation Committee of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), he must have been heartbroken.

I wonder what went on in Hashim Mbita’s mind as he breathed his last on 26 April 2015. What did the Retired Brigadier-General think of the xenophobic attacks in South Africa? As the former Executive Secretary of the then Liberation Committee of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), he must have been heartbroken.

When South Africa won its independence in 1994, he proudly exclaimed: “Mission Accomplished!” Twenty years later in a touching interview with Munyaradzi Huni, he thus bade us farewell: “I hope free Africa will remember the little I did for this continent.” He had done a lot as the Hashim Mbita Research Project on Southern Africa Liberation Struggles will attest. The lingering question is: Does South Africa remember him?

For sure, the establishment in South Africa remembers what he did, especially when a part of it was exiled in Tanzania during Apartheid. To that end it decided to bestow – in gold – the Order of the Companions of OR Tambo on him for his “exceptional and gallant support of African liberation movements and his tireless efforts in ensuring that the struggle for freedom throughout the African continent bore fruit[s].”

But those “˜fruits of Uhuru’ seem to not be sufficient enough for South Africa to share with their brothers and sisters across the Limpopo. For the average South African, little is known or remembered about the sacrifices that the likes of Mbita, who were on the Apartheid regime’s hit list, made. Hardly known in those streets, he himself could, like many others, have been a victim of xenophobic attacks.

As someone who spent six years in South Africa, I refuse to simply blame those whom the establishment has failed. I recall how afraid I was in Cape Town when I heard about seemingly isolated attacks on foreigners, which included one individual being thrown out of a train. We had to be so careful. One day I visited Pretoria and experienced one of the scariest days of my life.

Since I could only get a British Visa from there, I boarded a minibus that was heading to the famous township of Mamelodi. My map, and what I gathered from the people I asked, indicated that somewhere along the way the bus would pass by the Embassy. I didn’t bother to ask anyone inside the “˜taxi.’

My fear was that I was too dark and could not speak any South African language. When I realized we were moving out of town I had to ask. All hell seemed to break loose. One old man asked where I was coming from. Instead of saying Tanzania, I said Cape Town. “No, it can’t be, you must be from Cameroon, you people are selling drugs to our kids and destroying them!” Some other passengers chipped in. By the time we arrived in the township, which I only knew one thing about – its famous football team, Mamelodi Sundowns – I thought that my final day had at last come. “My son this Mamelodi, welcome to Mamelodi”, one middle-aged woman told me. Someone else said that the driver would help me.

To run away or to stay, that was the question. I opted to hang on there though the driver had not spoken any English during the journey. Instead of turning the taxi around and parking in the queue for those that were heading back to Pretoria, he started moving deep into the neighborhood. We stopped at his home and all I could do was switch off my cellphone (I knew that cellphones often attracted muggers), pray and surmise that maybe he was getting some more manpower to deal with me. Then, lo, we went to a playground.

No xenophobic attack occurred. He seemed to reprimand his son for something. Then he started driving back to Pretoria. On the way there was a taxi that was competing with him. Suddenly he spoke in English, asking me to open the window so that they could converse.

Guess what? He stopped right in front of the door of the Embassy. He gave me back my map and wished me luck. The moral of the story is that xenophobia is complex and thus cannot be generalized. What we need is to make sense of it.

Can we afford to simply ignore the rationale behind a publicly made (yet anonymous) statement like the following, that does not seem to dismiss the roles Mbita and his comrades played, yet smacks of xenophobia: “We have just come out of an oppressive bloody Apartheid system while you North of the Limpopo had been enjoying freedom since 1960, 1975 and 1981 [sic] respectively. We remember those proud milestones. But we are all still developing countries and our development must [not] be impeded with so many strangers and illegals in our midst”?

Some of us believe in the principle that “no one is illegal,” but that should not stop us from trying to make sense of what is meant by ‘impediment’: “But there are signs of drug-dealing, prostitution and other criminal acts that you conduct – sometimes in cahoots with desperate locals.” Another South African, Sanele Wanda (quoted in this article), thus put it innocently: “Not all of them are drug dealers, but it is a known fact that they dominate the drug market. We are tired of acting like we don’t mind all of this.” After reading him, I quipped: Truth be told, I met more than 5 Tanzanians selling drugs in Cape Town back in the days; Sanele may have a point.

Mbita would also have seen the point because the drug market is a cross-border problem, just like the way the gun market was/is. As such it is something that needs to be dealt with at a continental level, that is, through Pan-Africanism. One of those five Tanzanians was a good boy but he had a hard time in Tanzania. When he got to South Africa, in the mid 1990s, he started “˜legally’ by working as a dishwasher but life was not as rosy as he thought. His problem, then, stemmed from the developmental problems of both countries.

Jobs may not be enough. However, we should pay attention when the likes of Sanele state: “I used to work as a security officer here in the Durban city, but my job got snatched away from me by a foreigner who promised my boss to do the same job at half the salary.” Grievances are as real as they are imagined. Showing statistics about how “˜foreigners’ are actually creating jobs in South Africa may be appeasing to the “˜middle class.’ But such statistics, factual as they are, may not appear real to Sanele and his close compatriots. What ought to be done is not only to create public awareness about the roles of – and relationships between – Africans across the borders of our countries, but also to integrate our economies through fair trade so we can rebuild the continent and its people.

The Pan-Africanism that Mbita upheld can still address the root causes of xenophobia. South Africa can remember him by reconnecting with the continent at a level other than big business. For Mbita, “˜mission accomplished’ was to be the liberation of all the people of Africa.

Chambi Chachage is a researcher in African Studies at Harvard University.

Well written piece. Includes the personal as well as the social political. Asking questions as well volunteering answers. An excellent tribute to one of Tanzania’s glorious sons, Hashim Mbita. Well known in his hey days.

Chambi Chachage also hints. He offers the enduring problem with us not writing enough memoirs and chronicling events for future generations. I for one, although I knew Hashim Mbita during the days that I was reporter, only recalled him as Major Hashim Mbita. I was not aware that he had reached the rank of Brigadier General. I had actually forgotten him. What does this illustrate? WE are not documenting our lives and the lives of Significance… as should be. Archiving is one of Africa’s most visible glowing weaknesses.