Bashir and South African Foreign Policy: Beyond Considerations of African Unity – By Christopher Williams

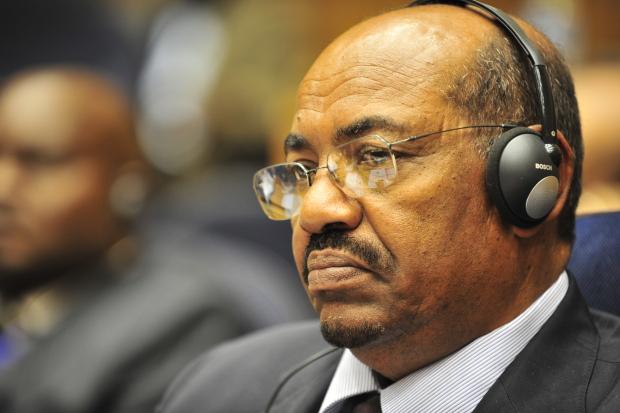

The diplomatic and legal crisis precipitated by Omar al-Bashir’s “escape” from Waterkloof Air Force Base in Pretoria on June 15 has prompted a heated debate amongst South African commentators and politicians. In the spotlight is the Zuma administration’s decision not to detain the Sudanese President despite a South African high court ruling that he stay in the country pending its decision on an arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court (ICC).

One of the clearest rationales put forth by those defending the decision not to arrest Sudan’s leader was the impact that such a move would have on South Africa’s relations with the rest of the African continent. Obed Bapela, chairman of the ANC sub-committee on International Relations, argued that if South Africa had arrested Bashir “definitely we would have isolated ourselves as South Africa.”

This justification is, at its base, about the importance of African unity, and it has existed since South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994. But too often, the maintenance of African unity has come at the expense of some of South Africa’s core values.

There are several reasons why South Africa’s foreign policy has paid special attention to African unity over the last twenty-one years. First, a newly democratic South Africa was eager to assert its African identity by participating productively in continental initiatives. Second, many South African officials felt they owed the continent a debt of gratitude for the support provided and suffering endured by other African states during the struggle against apartheid.

Third, South African policy makers saw it as in their national interest to help build a peaceful and prosperous continent. As the former foreign minister Alfred Nzo succinctly stated, “We cannot be an island of prosperity surrounded by a sea of poverty.” Finally, South African officials recall that past derivations from consensus African positions have led their country to be harshly criticized by other African states.

The most prominent example of this came in 1995 when President Mandela forcefully responded to the execution of nine Ogoni activists by calling for sanctions against Nigeria and harshly condemning its leader, Sani Abacha. While Mandela’s actions earned him plaudits from human rights activists, they garnered only opprobrium from the rest of Africa. No African states heeded Mandela’s call for sanctions, and South Africa was chided by the Organisation of African Unity. After the Nigeria incident, South African policy makers concluded that going it alone on the continent was not the way to go.

All these factors have elevated the principle of African unity to a guiding tenet of South African foreign policy. But more than twenty years after its transition, South Africa is no longer a newcomer to continental diplomacy; instead it is an established continental power.

While certainly a valid factor in all foreign policy deliberations, African unity must be weighed against other key South African principles such as respect for the rule of law, support for human rights and the creation of a rules-based international system.

When these principles come into tension with the principle of African unity it creates a situation of value complexity for South African officials. Value complexity is defined by the political scientist Alexander George as “the presence of multiple, competing values and interests that are embedded in a single issue.” This was certainly the case during the Bashir crisis in South Africa.

Arresting Bashir would have demonstrated the South African government’s commitment to the rule of law, its respect for international jurisprudence and institutions, and the importance it places on human rights. Not arresting Bashir indicated the importance South Africa places on African unity, and served to dramatically demonstrate the apparently strong view inside the ANC that the ICC is a fundamentally unjust institution.

This was indeed a tough decision that involved competing values, but the defence for the decision offered thus far has been unworthy of the difficult issues raised by this crisis. Most supporters of the decision have turned to classic (but unhelpful) coping mechanisms used to contend with complexity.

First, Mr. Bapela argued “We had to choose between the unity of Africa and the ICC and we choose Africa.” This is an example of devaluation, a coping strategy in which one of the values being traded off is downgraded to make the decision more palatable. Despite Bapela’s simplistic dichotomy, much more than South Africa’s relationship with the International Criminal Court was at stake: vital issues at the core of South Africa’s global identity such as a human rights-driven foreign policy, the rule of law and respect for international institutions were also involved.

Framing the decision as the ICC versus Africa also assumes that a united Africa would express outrage at the arrest of Bashir, which is far from a given. Bashir’s less than cooperative approach to AU efforts designed to bring peace to Darfur suggests that he is not terribly popular amongst some of his colleagues at the African Union.

Abiodun Oluremi Bashau, the Deputy Joint Special Representative for the African Union-UN operation in Darfur, recently stated that the biggest challenge confronting Sudan’s peace process was the “reluctance” of the government to engage in negotiations with the armed movements.

Though African rhetoric would likely be sharp if Bashir were arrested, continental sympathy and support for Bashir would not run deep. By casting the decision as Africa vs. the ICC, South African officials made their choice simpler, but not necessarily more sensible.

At the same time that supporters of the decision to expedite Bashir’s exit devalued or ignored the ideals they were sacrificing, they bolstered the case for allowing Bashir’s departure with a number of dubious arguments. First, Bapela claimed that “Obviously our businesses in Africa were just going to be shut down.” This hypothetical is hardly obvious.

While it is possible that Sudan may have asked South African businesses to depart, it is much less likely that other African states, no matter how much they disapprove of South Africa’s decision to arrest Bashir, would evict South African businesses. After all, many of Africa’s small economies would feel real pain if South African companies left.

Another argument regarding the costs of arresting Bashir, articulated by Mukoni Ratshitanga, was that South African soldiers attempting to keep the peace in Sudan would be held hostage by an infuriated Sudanese government. This eventuality seems unlikely because Sudan would be seen as striking back at AU troops, thus squandering any continental support it might have.

In addition, Ratshitanga argued that arresting Bashir would have “mortally damaged” the AU-led process to bring peace and stability to Sudan. Yet Professor Alex de Waal, who has been closely involved in the peace process, recently wrote of the current situation in Sudan, “There is no significant peace process that can be harmed, no process of democratization to be put in jeopardy.” In their attempt to bolster the case for allowing Bashir to leave, advocates of this decision have mistaken events that are possible, though unlikely, with events that are probable.

The devaluing of key trade-offs combined with the bolstering of dubious factors have allowed those who endorse the South African government’s decision to facilitate Bashir’s exit to paint a picture to the public (and perhaps in their own minds) that the decision to invite Bashir to South Africa and then permit him to leave in defiance of a court order was the only possible policy choice. It was not. A more forward-looking policy (and there was sufficient time to look forward) would have anticipated the uproar around Bashir’s arrival and might have led South Africa to request that Bashir send another Sudanese official in his place.

South African officials would also have needed to firmly explain to President Robert Mugabe (the official host of the AU summit) that South African law would force the arrest of Bashir if he entered South Africa. To contend with any continental criticism levelled at South Africa over this decision, Pretoria might have then led an African initiative to reform an ICC that many on the continent feel is unjust.

This approach would have accommodated South Africa’s concerns with African unity, while also honouring the country’s commitment to human rights and the rule of law. In addition, spearheading a project to reform the ICC would have positioned South Africa as leader in Africa, while also reinforcing its reputation as a state that is respectful of international laws and institutions, but also one that also seeks to make these institutions more equitable.

The precedent of African unity may be a helpful guide to policy formulation, but it should not substitute for thoughtful policy deliberation. In this case, other crucial considerations that should have informed South African policy were either ignored or dismissed. The result is that South African values have been tarnished and the credibility of the only international institution designed to hold leaders who commit the most insidious crimes has been damaged. South Africa might have done much better.

Christopher Williams is a PhD Candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, and a Visiting Lecturer and Researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand, and can be contacted at [email protected]

An important outcome though is that this issue has undoubtedly galvanised South Africa’s judiciary around what the country’s core principles ought to be.