How and why term limits matter

Opponents say term limits restrict democratic choice. The reality is they level the playing field.

On 15 September, over a thousand protesters gathered in Kinshasa to demonstrate against what they saw as President Joseph Kabila’s attempt to cling to power once his second term in office ends next year.

This was the first major government rally in the Democratic Republic of Congo since January when 40 people were killed in similar protests. But the phenomenon of citizens taking to the streets against a president seeking to circumvent constitutional term limits has become all too familiar.

In March, for instance, Burundi’s President Pierre Nkurunziza announced his intention to run for a third term despite a two-term limit, sparking a wave of protests and a failed coup. Nonetheless, Nkurunziza emerged victorious in July’s questionable elections, and political violence continues in Burundi, a country previously celebrated as a post-conflict success story.

Over the border in Rwanda, President Paul Kagame is also looking to stay in office after 2017, and in August, Rwandan media reported that a national referendum had demonstrated overwhelming support for abolishing the two-term limit. According to the state-owned New Times, “of the millions of Rwandans consulted […] only ten were opposed to the idea.” Kagame markets himself as a leader who can ensure stability, and given the traumatic memory of genocide, it is possible Rwandans prefer the devil they know. However, the referendum results are comically suspect.

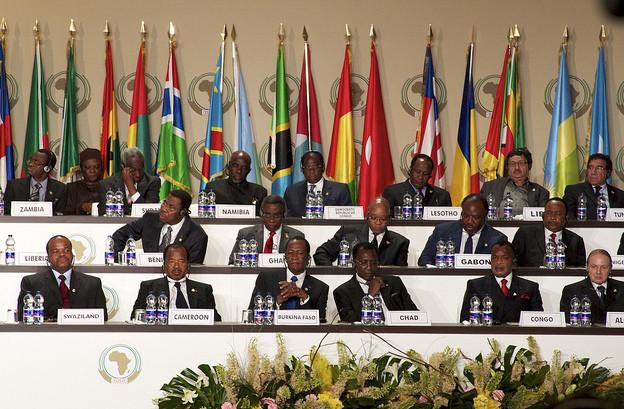

Elsewhere, civilians are protesting in Brazzaville against Republic of Congo President Denis Sassou-Nguesso’s attempt to change the constitution to stay in power. Congolese demonstrators say they are drawing inpspiration from the success of civil society in Burkina Faso, which successfully ousted longstanding President Blaise Compaore and prevented a recent military coup.

This is the context in which the likes of US President Barack Obama have appealed to Africa’s leaders to respect term limits. However, these calls have generally been dismissed by the continent’s long-standing leaders.

President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, for example, has characterised term limits as a Western attempt to “place a yoke around the necks of African leaders”. Mugabe argues that it is hypocritical to hold leaders in African countries to standards to which leaders do not necessarily adhere at home. Similarly, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni responded to Obama’s recent speech by saying that Ugandans have “rejected this business of term limits…I am there by the will of the people.”

Mugabe isn’t wrong. Many democracies do not have limited leadership terms. But these two presidents’ suggestion that more than two-decades of rule represents the will of the people is more difficult to defend.

In fact, a recent Afrobarometer survey showed that almost three-quarters of citizens in 34 African countries support restricting leaders to two terms. It’s not hard to see why: of the longest ruling non-royal leaders in the world, the top five are in Africa, and the likes of Cameroon, Western Sahara, Equatorial Guinea, and Zimbabwe have not only had the same ruler for decades but also rank among the lowest on Human Development indicators. Popular protests against the personalisation of rule meanwhile exemplify the discrepancy between the preferences of the political elite and the citizens they purport to represent.

The argument for term limits

The question of how to best reflect the will of the people in a country’s leadership cuts to the very heart of democracy. And the argument that people should be free to vote for whomever they want – even if that candidate has already been in power for two terms or longer – has some persuasive power.

However, all democracies face problems of representation, and emerging democracies in particular tend to face high levels of inequality and authoritarian legacies – and with regards to these challenges, term limits offer a promising solution.

Debate over term limits isn’t new, nor is it exclusive to Africa. In the US, for instance, some politicians favour scrapping term limits for state legislators. Opponents of the limits argue that they are anti-democratic because they constrain voters’ choices. But in reality, they do the opposite by lowering barriers to political participation – a keystone of democracy.

The 2005 Arusha Accords ending Burundi’s civil war recognised that the conflict stemmed from a “struggle by the political class to accede to and/or remain in power”. It enshrined term limits as a mechanism to ensure equal opportunity to serve in government. Limiting terms plays a stabilising role in states with authoritarian legacies, where political competition has a tendency to devolve into “zero-sum games”.

Authoritarian legacies in Africa have their roots in colonial state apparatuses, which were designed to facilitate resource extraction, and relied on state control over its subjects. The state became a bastion of wealth and a locus of exclusionary power, so access to the state guaranteed access to resources and security, usually at the expense of excluded groups.

In many former African colonies, the state remains a prize to be captured and maintained at all costs. In Rwanda, for instance, ethnic identity (crystalised through unequal treatment under Belgian colonists) became the decisive factor in Rwandans ability to access the state. Access to state resources became tantamount to the survival of one’s ethnic group and violence became the most effective tactic of regime change. Similar trends have occurred in Kenya, where the prosperity of certain ethnic communities has tended to correspond to the ethnicity of the standing president.

Term limits, however, work by shifting political preferences towards more stable equilibria. A voter may prefer her candidate gains and holds power forever; but, given the possibility that her candidate might be forever excluded instead, the risk-averse voter prefers a system where leadership change can occur in the future. Term limits render violence unnecessary by ensuring that newcomers have a real chance at challenging incumbents electorally.

Furthermore, while the “incumbent advantage” affects all democracies, it is particularly pronounced in poor, unequal countries. Because term limits guarantee leadership turnover, newcomers are more inclined to commit the high material and opportunity costs of entering the political arena.

Another advantage enjoyed by incumbents is the ability to stack key institutions and bureaucracies with supporters, developing patronage networks that trade material benefits for political loyalty. Term limits make it harder to established entrenched patronage networks, and arguably make them less valuable. Theoretically, term limits also incentivise leaders to develop equitable, effective institutions, with the knowledge that they will be subject to them once they leave office.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that leadership turnover has a positive impact on democratic development. Nigeria’s recent elections saw an opposition candidate, Muhammadu Buhari, win a free and fair election for the first time this year. Nigeria too experienced a crisis of third termism in its not-so distant past. President Olusegun Obasanjo’s attempt to amend the country’s constitution in 2006 was halted by the court. The Nigerian court’s ruling in favour of the constitution established a tradition of leadership turnover, the promising results of which are apparent today.

Today, Central African leaders are recklessly pushing their countries down a dangerous path by attempting to cling to power. It will not be the presidents themselves who suffer the consequences of civil conflict – elites rarely do. It will be the people whose interests these leaders claim to represent.

Term limits play a stabilising role by levelling the political playing field and have been shown to facilitate democratic development. In short, they offer a powerful antidote to many of the problems that lead to political violence. Increasingly vocal civil society groups across many African countries clearly recognise and are striving to uphold the importance of term limits – but it remains to be seen whether the region’s presidents will put the interests of their citizens ahead of personal ambition.

Claire Wilmot is a master of global affairs candidate at the University of Toronto’s Munk School. She has worked as a researcher in Kenya and South Africa.

The argument whether term limits are an imposition of expressive freedom of choice does not advance the argument in a significant manner.

The ordinal issue is whether expressive freedom of civic civil choice is available in many of the African sub-saharan nations.

The ordinal reason for the strict implementation and most strict enforcement of term limits [presuming limits have been agreed to by the legislature and are now embedded in statute] is to at minimum ensure choce change as now in Africa once elected the head of governance tends to oligarchy with entailed aggressive exploitation of resources in a manner means most transactional.

Power and the ‘big man’ ethos is still prevalent in Africa and therefore a legislative instrument promoting pluralist choice must be embedded so as to enhance the opportunity for at least minimum change—–“meet the new boss, same as the old boss won’t get fooled again”; as orchestrated by ‘The Who’ in a song sublime yet salient.

Term limits for the time being are necessary if the nations in Africa are to both prosper and grow in the promotion of pluralist values including fundamental respect tolerance for the expressive rule of law in process and procedure.

At this moment I am in Kinshasa, DRC where I am attempting to promote the civic civil social political public conversation in the advancement of process and procedure subject to non arbitrary rules.