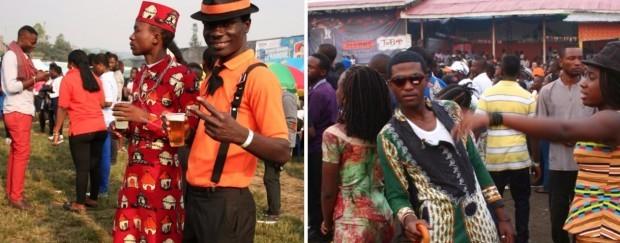

Les Sapeurs of the Eastern Congo: sharp, stylish, subversive?

For the residents of Goma, the Amani Festival was an opportunity to both wind down and dress up.

From the way they move to the rhythms of Nneka’s bombastic rock, it is hard to imagine that just a couple of years ago, the residents of Goma were left a little perplexed when a host of international bands descended on their hometown.

Back then, in February 2014, the Amani Festival was in its tentative first edition and the arrival of foreign musicians here in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo was an unfamiliar sight. But two years on and the three-day celebration of music and dance has become a well-known and well-loved event.

This year’s edition, held from 12-14 February, gathered 34 artists from the neighbouring region and beyond to perform for festival goers who were able to pay the $1/day entrance fee. 33,000 people attended.

In an area better known for instability and violence, the Amani Festival was started to celebrate the town’s newfound stability. Amani means “peace” in Swahili, and as one attendee told African Arguments, “The Amani festival means that we have peace now”.

This has not been the case for most of the last twenty years, and the first festival had to be postponed as the M23 rebels swept across the region. But since the militia’s defeat in late-2012, Goma has been relatively stable.

The same cannot necessarily be said of the surrounding more rural areas where around 70 militant groups still roam. But for those in town, Amani offers a welcome opportunity to forget about their troubles as they wave their hands to Ismaël Lo’s refrains or move to Werrason’s beats.

For the people of Goma, however, the event is not only about unwinding. It is also an opportunity to present themselves in the best light.

Many residents here enjoy dressing up when they go to church, and strolls through neighbourhoods afterwards often resemble catwalk fashion shows. But the festival brings dressing up to a whole new level.

Against the grey volcanic backdrop of Goma, festival goers don vibrant colourful outfits and – in a subtle contest with Amani’s performers – try to draw attention away from the stage and to their flamboyant selves. And they are often successful, with their informal mixture of fashion parade and carnival sometimes as spectacular as the official show.

The inspiration for these outfits comes from a wide array of influences ranging from classic European fashion, to hip-hop and bling-bling, to traditional African clothing, to science-fiction films. Sometimes all of these inspirations are combined into a single ensemble. Visitors paint their faces with bright motifs and wear a vast array of accessories, while those arriving in groups often wear matching colours and patterns. These fashion aficionados find their treasures in second-hand markets, receive them from relatives in Europe and the US, or tailor them themselves.

Christoph, a festival attendee notes: “Les congolais aiment la sape”. “Sape” which both means “attire” in French and stands for Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Elégantes (Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People) is the Central African form of dandyism.

La sape is much more than just a passing trend. The phenomenon began under Belgium’s colonial rule, when the assimilated Congolese elite – the so-called évolués – dressed in elegant European clothing to distinguish themselves from their compatriots.

But since then, the meaning has significantly shifted, particularly under the long rule of Mobutu Sese Seko from 1965 to 1997, when the military dictator embarked on a programme of authenticité in which Western culture was denounced. Part of this programme entailed the invention of the abacost – an abbreviation of à bas le costume (“down with the suit”). This tieless shirt inspired by Chairman Mao’s suit became the national dress, and for much of Mobutu’s rule, certain Western-style outfits were banned. Defying this order by dressing up in sharp suits and ties thus became a symbol of resistance against the regime.

For many Congolese today, wearing extravagant clothing demonstrates dignity in a world of poverty. For the sapeurs, style is a religion and some take pride in spending their last cents on the latest fashion. But hidden in this apparent materialism, there is also an implicit political critique moulded for the Congo’s current concerns.

[See: Podcast – Electoral Politics in the DR Congo with Jason Stearns]

Under Mobutu, the musician and “pope of la sape” Papa Wemba refused to talk about politics and turned all his attention to rumba music and extravagant styles. Abstaining from politics was the only option for critique available in the dictatorship. In a similar way today, the decision to refrain from politics and invest all one’s energy into fashion can be seen as the only logical way to respond to a political system in which ordinary people feel powerless. Or, as Justine, a visitor of the festival puts it, “Politics has betrayed us. We’re here to listen to music and forget the rest”.

Indeed, despite the country’s vast natural resources, poverty and unemployment remain high, and the unpopular President Joseph Kabila looks intent on staying in power beyond his constitutional two term limit which officially expires this year. And the devastating situation in Burundi just 200 km away is giving the people of Goma a frightening example of where such eagerness for power can lead.

[See: DRC: The final countdown to the 2016 elections or just another transition?]

[See: In the shadow of genocides past: can Burundi be pulled back from the brink?]

In a peculiar reversal of la sape, the Amani festival also saw a number of visitors turn up dressed like Mobutu, wearing colourful abacosts and donning thick-framed glasses, a toque and walking stick. “Congo was important then”, explains one imitator his admiration for Mobutu’s style.

On the face of it, these Mobutu stylists add even further to the eccentricity, flamboyancy and spectacle of the Amani Festival. But as with other Congolese fashions, there may be another sharp political critique lying beneath the surface – in a widespread sense of powerlessness and disaffection with the current situation, some Congolese may be seeing the current situation as so helpless that they forget about the destructive sides of Mobutu’s regime and only remember his few positives.

Alex Kopp is a freelance journalist based in Bukavu, DRC.

Photo credits: Alex Kopp

This is the DRC I adore as the majority of citizens living in DRC only wish to work in a job which provides for their families as well as ensuring a modicum of respect within the DRC civic civl society. ‘Style’ is an expression of elan as well in projection of civic cultural individuality.

Gainful employment with integrity along with strong education institutions are what the majority of DRC citizens crave. The tragedy is that the economic political elites have failed to these citizens manifold.

Therefore according to the DRC Constitution, elections must be conducted in 2016.