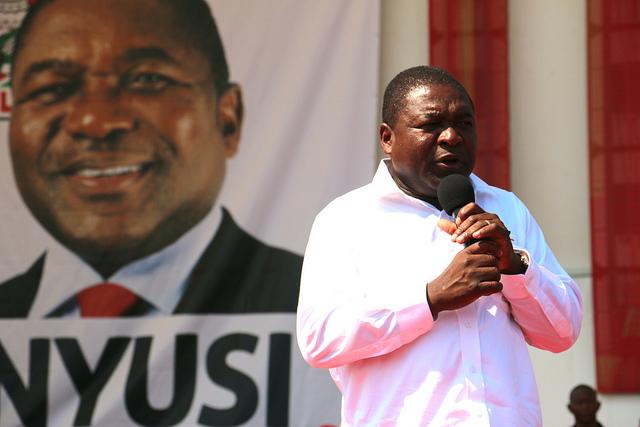

Mozambique: Nyusi grapples with Guebuza’s toxic legacy one year on

When Filipe Nyusi became president, he inherited three painful problems rooted in his predecessor’s lack of foresight. Twelve months on, he is still reaping the whirlwind Guebuza sowed.

Attacks on Mozambique’s main highway by suspected Renamo gunmen last week were a harsh reminder that President Filipe Nyusi is still struggling to deal with the mess left to him by his predecessor, Armando Guebuza.

Nyusi took to office on 9 February 2015, replacing his counterpart from the ruling Frelimo party who had led the country since 2005. Since then, the former defence minister has tried to make his mark, but his year-long reign has so far occurred under the shadow of his predecessor’s questionable policies.

Low level guerrilla activity by the opposition Renamo party has generated much concern across Mozambique and beyond, but it is just one of three particularly toxic legacies Nyusi has inherited.

Renamo’s resurgence

Renamo was formerly a guerrilla movement that waged war against the Frelimo government. Backed by apartheid South Africa, Renamo battled for 16 years before a peace accord was signed in 1992. Realising it could never win the conflict, Renamo laid down its arms and become a political party in a multi-party system.

At the time, it was said that such a settlement was only possible because Mozambique had no mineral resources. But this changed when, in the early 2000s, valuable coal reserves and then one of the largest gas fields in Africa were discovered.

The potential for profit from these findings was huge − billions of dollars were spent on infrastructure, while contracts and land deals yielded considerable rewards. Much of these went to Frelimo elites who set up businesses, sometimes with very shady foreign companies.

In light of this windfall, Renamo demanded that the proceeds of Mozambique’s bounty be shared with opposition parties too, but President Guebuza refused. Reaching a head in 2013, a frustrated Renamo returned to the bush and revived low-level guerrilla activities. A new peace deal was agreed, but collapsed. Afonso Dhlakama, Renamo’s former commander-in-chief and now political leader, maintained his call for greater powers and finances. But still, Guebuza refused to budge.

Fast forward to today and Renamo continues to launch low-level attacks, such as the assault on 11 February when gunmen shot at traffic on the country’s main north-south road, injuring three people. Unlike his predecessor, President Nyusi sees the importance of buying off Dhlakama and wants to negotiate, but this process has hit some snags.

Unknown gunman last year twice attacked Dhlakama’s armed convoy in Manica province, and on 9 October police raided his house in Beira. Then, on 20 January 2015, Renamo secretary-general Manuel Bissopo was seriously injured and his bodyguard killed in a drive-by shooting. The attack on Bissopo ended any chance of negotiation and Dhlakama, rightly fearing he could be a target, retreated to a former Renamo camp.

Five years ago − before it was clear how valuable Mozambique’s gas was and before Renamo showed how disruptive a few guerrillas could be − Guebuza could have won a relatively cheap settlement. A couple of hundred million dollars would have probably have been enough to appease Renamo. But now Dhlakama wants much more, the fighting continues, and Nyusi is faced with a much bigger problem.

Fishy debts

The second unfortunate Guebuza legacy that Nyusi is still contending with is the fallout from the controversial $850 million Eurobond the former president approved in secret.

Launched in 2013, much of the money raised from this surprise move went to fund a new tuna fishing company, Ematum, which is part owned by Mozambique’s security services. The details of this deal were fishy from the start and have raised many concerns of fraud, but another $500 million from the Eurobond has not been accounted for at all. The government refuses to explain where this huge sum has gone, though many believe it went to Guebuza as a retirement gift as well as to his allies.

Although Mozambique earned little from coal and nothing from gas under Guebuza, it did gain substantial capital gains taxes as pieces of ownership of the natural resources changed hands. Guebuza’s government assumed that continued revenues from these deals would enable the Eurobond to be paid off easily. But the collapse in commodities prices has put an end to that plan, leaving Nyusi’s government with the enormous debt to pay off itself.

Adding insult to the injury Nyusi inherited, donors, who still provide a fifth of the government budget, were also outraged by the controversial Eurobond deal and withheld aid last year. This forced Nyusi to go cap in hand to the IMF which approved a new $286 million loan last December, adding to Mozambique’s debt obligations.

Food prices rising

This links to a third inherited problem. For the ten years under Nyusi’s predecessor, few efforts were made to support local production or industrialisation, and in the capital Maputo at least, the majority of food and consumer goods are imported from South Africa.

Thanks to an inflow of aid money and capital gains taxes, the government has typically been able to keep an overvalued exchange rate, making these imports cheaper. There were attempts to devalue its currency in 2008 and 2010, but rising food prices sparked riots and the government decided instead to keep the exchange rate level.

This policy was facilitated by a ten-year decline in the trade-weighted value of the US dollar. But over 2014 and 2015, the value of the dollar jumped 25% and Mozambique was finally forced to devalue its currency late last year. According to the Bank of Mozambique, this led to 4.8% inflation in December and 2.5% inflation in January.

With food prices set to continue rising − in large part thanks to Mozambique’s failure to support local production and heavy dependence on imports − will there be riots again?

President Nyusi inherited three big problems rooted his predecessors’ lack of foresight. A deal with Renamo was possible five years ago, Frelimo insiders could have stopped the Ematum loan, and earlier devaluation and the promotion of local production could have kept inflation low.

But it was easier to do nothing and not rock the boat. And now, one tough year into his first term, Nyusi is still reaping the whirlwind that Guebuza sowed.

The EMATUM is issue however was not a ‘Eurobond’ such as the loans which countries like Kenya, Ghana and Zambia have issued in recent years. Eurobonds have strict requirements with regard to disclosure of method, structure and use of funds. The issuing document often runs to scores of pages. EMATUM was a debt ‘guaranteed’ by the Mozambican state, without that state’s knowledge; although never circulated, lenders and investors’ representatives have confirmed that loan documentation ran to half a dozen pages, ten at most. CW