Some new beginnings? The challenges facing Central African Republic’s new president

What are the main issues facing President Touadéra and how well-equipped is he to deal with them?

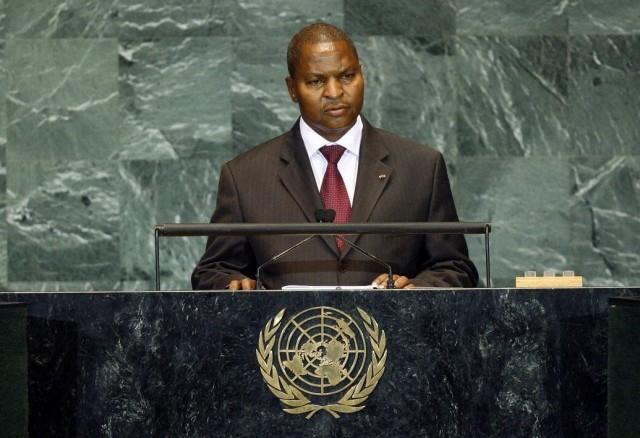

Central African Republic’s President Faustin Archange Touadera. Credit: UN Photo/Erin Siegal.

With a new and democratically-elected president in office, a degree of optimism has returned to the Central African Republic (CAR), though the challenges he faces are huge.

Faustin Touadéra, a former prime minister and maths professor, emerged victorious in the presidential elections in March. He named his first cabinet last month and will be hoping his new government can help the CAR leave behind decades of poor governance and rebuild a country that remains a fragile state after years of conflict.

Since March 2013, when the Séléka rebels ousted President François Bozizé, thousands of people have been killed in violence, while around one fifth of the approximately 4.6 million population have been forced from their homes. Many of the militia that have been part of the violence are still operational, the capital Bangui is religiously polarised after fighting became divided along Muslim-Christian lines, and the state’s capacity is weak.

Under these conditions, concerns were raised about the prudence of holding elections, but although repeatedly delayed, the polls were eventually held in relative peace as Touadéra beat former PM Anicet-Georges Dologuélé with 62.7% of the vote. The process also received credibility through its support from both international partners and crucial domestic stakeholders such as major ex-Séléka groups like Noureddine Adam’s Front Popularie pour la Renaissance de Centrafrique (FPRC).

The success of the elections has certainly been a positive step forwards for the CAR and bestowed upon Touadéra’s presidency much more legitimacy than that of his predecessor, Catherine Samba-Panza, who was seen as a temporary leader and lacked authority outside Bangui. As Paul Melly, Associate Fellow of the Africa Programme at Chatham House says, “Touadéra will be in a much stronger position to take forward the process of rebuilding social and political cohesion”.

However, the challenges he faces are enormous. Here are some of the main ones:

Unifying Bangui

The semblance of harmony that the election brought is unlikely to be long-lasting, and Touadéra is faced with a vast and diverse opposition; 30 candidates participated in the first round of the elections.

However, Touadéra’s decision to give cabinet positions to some defeated candidates who supported him in the runoff should help pacify certain elements. This could also provide a sense of political unity that will aid the new president in his attempts to reunify a country that has been deeply divided by violence between the ex-Séléka and so-called anti-Balaka militias.

In the course of the conflict, districts in Bangui became demarcated according to religion as the violence took on a religious dimension between the predominantly Muslim ex-Séléka and largely Christian anti-balaka. As fighting erupted in the capital, the Muslim population almost entirely fled with the number of Muslims living in Bangui decreasing from roughly 145,000 in 2012 to just 900 by early 2014.

Touadéra has pledged to address these divisions as a priority. And in attempting this, he has the advantage of not being seen as closely linked to either the ex-Séléka or anti-Balaka, nor either of the two previous governments. Despite being a prime minister in Bozizé’s government between 2008 and 2013, Bozizé backed Dologuélé in the elections. This has allowed Touadéra to gain some distance from the former president, who is accused of vast corruption and mismanagement in office, and presented him with a fairly clean slate.

Getting funds

As one of the world’s poorest countries with very few functioning institutions, Touadéra will need to address funding shortages, corruption and the state’s weak capacity. “Even for Touadéra , rebuilding the state will be a big task”, says Melly.

The new president will have to rely predominantly on international financing, most likely from France and the IMF, to fund development projects, while he may also seek to rebuild the mining sector. Before the conflict broke out in 2013, diamond exports amounted to half of the country’s total exports and 20% of budget receipts.

However, revitalising this sector will be difficult and financial shortcomings are likely to continue to plague CAR’s development. Exploitation of mineral resources has historically occurred solely through artisanal methods as industrial mining companies have been deterred by the sector’s opaque management and high levels of taxation.

Touadéra’s reappointment of Minister of Mines, Energy and Dams, Leopold Mboli-Fatrane, who was in charge of the mining sector under Bozizé when corruption was rife, does not bode well in this respect.

Ending the violence

Violence is likely to continue in the CAR, albeit in a more localised way than during Samba-Panza’s presidency. This danger was highlighted shortly after Touadéra’s election when a group of ex-Séléka militants launched an attack on N’dim in the northwest near the border with Chad and Cameroon.

Long-term political resolution with CAR’s rebel groups is likely to be difficult while members of the largest militias – the anti-balaka and ex-Séléka – are excluded from government. In contrast to Samba-Panza’s government, Touadéra chose not to include representatives of either group in the new administration, a move which will undoubtedly anger them.

This decision will also make it much harder to engage either insurgent group in demobilisation, disarmament and reintegration (DDR) campaigns. Efforts at DDR will also be undermined by a lack of resources for such a large operation, particularly as French troops, which have been deployed in the country since late-2013, plan to leave by the end of 2016.

However, not only will the French departure hamper attempts to begin post-conflict reconstruction, it will also impede the government’s efforts to maintain order. The national army is fragmented at best and even with the assistance of French and UN troops at present, it is struggling to keep peace outside Bangui. For instance, the Ugandan rebel group the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) is thought to have kidnapped more than 200 people in the east of the CAR since the start of 2016, while reports emerged in mid-April that ex-Séléka forces were amassing troops in Kaga Bandoro in the north.

Strengthening the state

Underpinning many of Touadéra’s challenges are the state’s limited resources and restricted reach. The government’s presence in the capital and southwest can be gradually re-established, but it will struggle to assert itself in the north and east where governance has always been limited. Bangui may begin some infrastructure initiatives over Touadéra’s first term in order to bring the more remote parts of the country closer to the capital, but these projects will require international financing and likely years to implement.

Additionally, establishing effective local institutions in more remote areas will require the removal of the governance structures put in place by rebel groups. Currently, armed movements, which control pockets of territory in remote regions, are able to extract “taxes” from residents in return for security. The removal of these structures will require extensive DDR programmes, which seem unlikely in the near future.

It is improbable therefore that the state will gain full control over the country for many years to come, and while there will be gradual progress in upholding law and order and introducing basic services in the capital, more substantial, far-reaching change is likely to take much longer to be achieved.

Jessica Moody is a freelance political risk analyst with a focus on West and Central Africa. She is due to start a PhD on post-conflict reconstruction in Cote d’Ivoire at King’s College London in October 2016. Follow her on twitter at @JessMoody89.

President Touadera can succeed so long as constitutional government and security are focused on with health, and education also a priority.

Notsure if him being an Atheist if he actually was one, would help with the religious issue. But I doubt anybody there is ready for a no faith head of state.

Jessica you have provided great insight. I have a few questions. Do you know the ethnic makeup of the army? What ethnic cleavages and patronage systems operate in the security forces and where their loyalties lie? I wrote this because the Army in Africa has been the single most destructive entity on that continent. It has usurped the state over 120 times since independence with over 200 failed attempts. An overriding reason being that unlike Western armies that have an outward posture, the culture of the majority of African armies is inward. In that their mission is to control their own citizens. In this case, not very different from the colonial armies that preceded them.