In Defeat, Defiance: Why Uganda’s repression of resistance could come back to haunt it

By narrowing political space and clamping down on the opposition and media, President Museveni is ensuring future demands will have to find expression through alternative channels

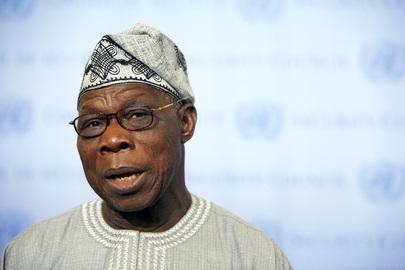

The government’s message to the opposition since the disputed elections has been clear: any protest movement will be nipped in the bud. Credit: Brian Harries.

Since the chaotic elections in February, the political atmosphere in Uganda has been tense and the capital Kampala under siege. Columns of between eight to ten soldiers can often be seen strolling the streets, while navy blue police pickup trucks can be spotted positioned strategically around the city equipped with teargas and gun-wielding officers. Key opposition figures have been routinely placed under house arrest, social media has frequently been switched off, and the main opposition leader Kizza Besigye is now in prison facing charges of treason.

This has been the government’s response to the opposition’s rejection of the heavily disputed election results in February, which saw the 72 year-old Yoweri Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) party – in power since 1986 – win a fifth term in office with over 60% of the vote.

In the wake of the contested elections, the opposition had hoped to mobilise discontent in opposition strongholds through its so-called Defiance campaign and harness it into a countrywide movement. Yet the campaign – which has included a demand for an independent audit of the election results, a counter swearing-in ceremony, weekly Tuesday prayers, and other creative actions – was met head on by the government and police, and has now been thwarted. Or so it seems.

A Ugandan Spring?

The government’s response to the opposition’s planned protests has been strong, cunning and urgent, possibly revealing its concerns about a potential ‘Ugandan Spring’. And it would not be the first time Museveni’s government has dealt with such a fear.

Back in 2011, as youth-led protest movements in Tunisia and Egypt deposed long-standing strongman presidents in the so-called Arab Spring, Uganda too witnessed its most serious challenge to state authority since the NRM came to power too as thousands took to the streets in the Walk to Work protests.

These demonstrations were partly inspired by events in North Africa, and certain similarities were striking. In Uganda as in Egypt, for instance, the reins of power were in the hands of a three-decade-old regime, heavily funded by the US, and which was now faced with a population full of unemployed youths.

Yet, by contrast with their counterparts further north where protesters called for outright regime change, the Ugandan opposition’s demands were fairly timid and its message framed in economic terms focused on rising fuel and food prices. Though it attracted thousands to the streets, this ‘political walking’ – to borrow Adam Branch’s phrase – was eventually contained as police responded with repression, mass arrests and teargas, though the experience left an indelible mark on Uganda’s political psyche.

The recent Defiance campaign, coming just five years later, can be seen as a reincarnation of the Walk to Work movement, albeit now bolder in its objectives. Unlike its predecessor, the Defiance campaign is unapologetically political in its demands, challenging the very legitimacy of the Museveni regime. The movement’s rejection of election results has sent an explicit message that the government has not missed: namely, that the opposition does not accept a regime it deems to be built on injustice.

By deploying so heavily and in advance, the regime’s message back has been similarly crystal clear: any protest movement will be nipped in the bud before it crystallises. The government has shown that it will take no chances and this aggressive strategy seems to have paid off, at least for now. The streets have been largely clear of protesters, and Museveni comfortably took his oath as he was sworn in last month.

Dissent through other means

On the one hand then, it seems like it is business as usual again in Uganda. But on the other hand, the narrowing of political space, far from containing popular dissent, may have made it even more likely that any popular demands in future will have to find expression outside the formal mechanisms of the existing political system. A previous piece on African Arguments suggested that the choice open to opponents of the government now is of whether “to break or to build”, and with the government clamping down forcefully on any form of opposition, it may be making “to break” the only feasible option.

[See: To break or to build: The choice now facing Uganda’s opposition]

With faith in the electoral system eroded, popular protests outlawed, and the media gagged (with journalists even banned from covering the Defiance campaign), Ugandans’ latent dissatisfaction and energy may have to find new forms of articulation – ones that might be raise the likelihood of a Ugandan Spring rather than stem it, as the government intends. After all, the protests that rocked North Africa in 2011 were driven not by an overly critical media, as NRM logic has it, but by widespread discontentment amid a politics of repression.

The prospects of the current Defiance campaign might be bleak for now, but in the longer-term, the more radical nature of its demands calls for deeper reflection, and the more that Uganda’s political space shrinks, the more likely it might be that popular discontent will have to seek alternative channels, even at the risk of violence.

If the regime’s dwindling legitimacy is to be salvaged therefore, there must be a significant shift in the way power functions in Kampala. The iron-fisted approach – which is fast becoming a hallmark of NRM rule – may have crushed two protest movements so far, but its sustainability is questionable. Civil disobedience cannot ultimately be quelled by boots and jets, but only by processes of dialogue. Any long-term government strategy will thus have to display a willingness to tolerate a degree of opposition and criticism.

In this regard, a free media, room for popular protest, and free and fair electoral competition will all be essential for averting future unrest. Whether Museveni will concede to such reforms is of course doubtful, but so is the possibility that popular dissent – suppressed but also inadvertently stimulated by increasing political repression – will cease to look for new fault lines in Uganda’s ever more closed political system.

Michael Mutyaba is a pursuing an MPhil in Social Studies at Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR), Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. His research specialises in contemporary African politics, especially the broad fields of governance, civil society, state building and democracy.

[repression of resistance ]…Could be also be said about America.

Nice forecast. Museveni is defining the pace and outcome of his regime.

Yes let him define the pace, tempo and outcome of his regime.

its time for Ugandans to seek for alternative channels, even at the risk of violence