No, cobalt is not a conflict mineral

Global demand for cobalt is estimated to more than quadruple in the next ten years. Mislabelling it particular hurts vulnerable Congolese miners.

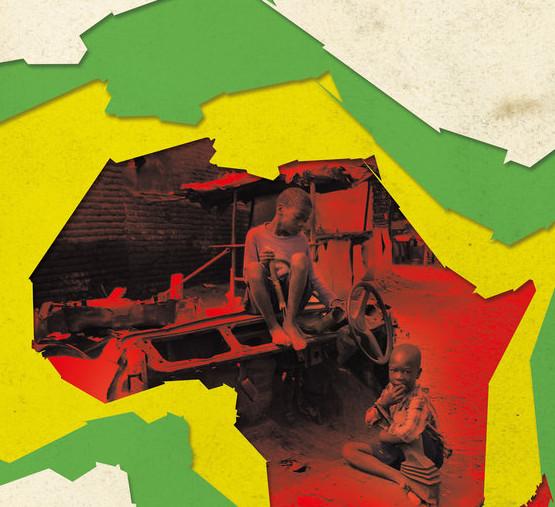

Credit: Clint Budd

Wakanda’s vibranium extolled in Black Panther may be fictional but is not very far from reality. A remarkable metal used in emerging technologies – from cell phones to electric cars – has the potential to create a more responsible and sustainable lifestyle for the global community. Cobalt is expected to become the “new oil” as the world transitions to a low-carbon future.

However, cobalt has faced bad press in the last few years due to human rights violations identified in the mines where it is sourced. Child labour and hazardous working conditions have become associated with its production in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) where about two-thirds of global production occurs.

It has also gained notoriety as a conflict mineral following concerns about other minerals mined in the DRC. But this label is false. It is a view rooted in misinformation and confusion that needs to be fixed.

Cobalt is not a conflict mineral

Conflict minerals refer to a specific group of minerals – cassiterite, coltan, wolfram and gold – that are sometimes produced, traded, taxed, or looted by armed groups in the eastern DRC. At the moment, most armed groups in the region are not connected to mining and the Congolese government has validated hundreds of mining sites as conflict-free. But some militants do profit from those activities and perpetuate insecurity to protect their business interests.

Cobalt does not fit this description. Instead, this mineral is being mined in the comparably peaceful Copperbelt area of Haut-Katanga and Lualaba Provinces (within the former Katanga). These areas are in the Southern region, more than 1,000 miles away from the east.

While all artisanal and small-scale miners in the DRC may share the same working conditions and difficulties, they should not be put in the same basket. Concerns surrounding cobalt mainly relate to governance and labor conditions, including child labor, rather than to the kind of dangerous conditions and conflict that can be observed in some mining areas in the Eastern DRC.

The effects of mislabelling

Citing cobalt alongside other conflict minerals has unintended and negative effects. It affects foreign investment in the cobalt industrial sector, which accounts for about 70-80% of the country’s total production and, by extension, the DRC’s efforts to grow its revenues. Further, it directly impacts the livelihoods of thousands of people who depend on the artisanal mining of cobalt to survive.

As international and Congolese researchers stated in an open letter, “in demanding that companies prove the origin of minerals sourced in the Eastern DRC or neighbouring countries before systems able to provide such proof have been put in place, conflict minerals activists and resultant legislation – in particular Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act – inadvertently incentivize buyers on the international market to pull out of the region altogether and source their minerals elsewhere.”

The Dodd-Frank Act is a piece of 2010 US legislation to ensure US companies determine they are not dealing with conflict minerals. Because of it, some industry actors found it easier to avoid sourcing from the DRC altogether. This has made artisanal miners, their dependants and people in related industries more vulnerable. As a recent report from an DRC-Deutsch mapping project states, “the artisanal sector provides much more jobs than the industrial sector in the DRC”. Artisanal miners, who usually come from poor families, have often been able to improve the living conditions of their families and enhance their financial capability.

What can be done?

The OECD, the UN and other international actors rely upon Due Diligence requirements as a route towards addressing the labour issues in artisanal and small-scale mining. These requirements compel businesses to trace their supply chains back to smelters and refiners in order to avoid risks and source responsibly from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. This promising international approach needs to be further tailored to cobalt extraction alongside an internationally recognized and locally acceptable certification scheme.

At the local level, a more inclusive approach is needed. The most vulnerable artisanal miners – who tend to operate in informal and illicit smuggling and don’t comply with labour or environmental laws – need to be brought in. Instead of disengaging them, organisations should listen to them, educate them, and support their development by maintaining them in the formal market so that they can progressively improve labour conditions. Such a model has been developed by a group of experts, should be explored further and adapted to the context in which cobalt is mined in the DRC.

For its part, the Congolese government has pledged to eliminate child labour and hazardous labour conditions in artisanal and small scale cobalt mines by 2025. President Felix Tshisekedi has been working on fostering national institutions and improving good governance including in the mining sector where cobalt has become a “strategic mineral”.

Cobalt is not exactly the same as Wakanda’s vibranium. But it’s also not the same as the conflict minerals produced in other parts of the DRC. It is a mineral of vital importance for industry worldwide and a key element in a global transition to a low-carbon future. Benchmark Mineral Intelligence forecasts suggest that “global demand for cobalt will be 300,000 tons in 2029, compared to the estimated 70,000 tons used in 2019″. Those who produce it deserve a fair return on their labour.

By viewing cobalt as a strategic rather than conflict mineral, and if miners, the Congolese government and international companies can work together, a win-win-win scenario for cobalt supply chains is possible.

The DRC will undoubtedly be a key player in all this.

Vous confondez Coltan et cobalt .

Le Coltan correspond à la niobiotantalite un oxyde de niobium et tantale qui est effectivement utilisé dans l’industrie du portable . Rien à voir avec le cobalt . Et je ne comprend pas la référence au vibranium qui n’existe pas ! C’est comme si vous parliez de la kryptonite de superman .

Very nice article on DEC mining sector. As you mentioned, cobalt is not a sourced from conflict locations of DR Congo as people tend to present it. After working with organizations in the mining sector, I can just add that a lot of efforts are in place already to ensure artisanal mining sites comply with international regulations related to the diligence and traceability.

This insightful article describes how a switch of paradigm can affect a community, a nation, a continent… Many misleading information are intentionally spread to serve the interests of those who benefit from them. Being yourself a native of the DR Congo, you definitely understand better the situation and let’s hope policie makers will gain more insights by reading your publications. No one shall never victimize himself in this globalization setting we are in. When you know, you know… Keep it up#positive mind#musirimu

discontinuing cymbalta side effects of duloxetine cymbalta 60 mg cymbalta generic ’

chlorowuine https://chloroquineorigin.com/# hydochloroquine