Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

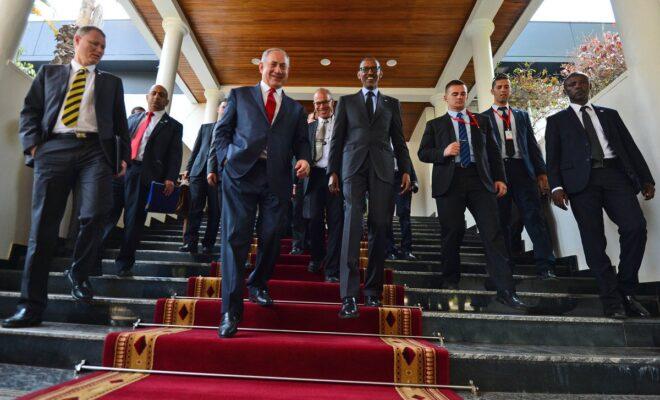

Netanyahu’s state visit to Rwanda 2016

Israel in Africa deals with the evolution of Israel’s strategy in Africa under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu, the country’s prime minster since 2009. When I finished working on the book about a year ago, Israeli leaders seemed to be locked in a political battle whose outcomes were difficult to predict. Ultimately, however, corruption charges and three rounds of elections in which his loyal right-wing coalition failed to win a majority did not stop Netanyahu from forming a new coalition and being sworn in once again as Israel’s prime minister earlier this year.

Israel now has a new foreign minister: former Chief of Staff Gabi Ashkenazi, who, together with former Chief of Staff and now defence minister Benny Gantz, competed in the elections as an opposition to Netanyahu but ultimately abandoned the effort to replace him and joined his coalition. Neither offers a real alternative to his political vision nor possesses the power to dramatically influence Israel’s international strategy.

Moreover, as Israel in Africa demonstrates, Israel’s activities and leverage in Africa are shaped by such a wide range of actors that are beyond the immediate control of the Israeli government that changes in the leadership in Jerusalem can only go some distance in transforming what Israel looks like or does in the continent. We can therefore see how the main trends outlined in the book continue to shape Israel’s efforts in Africa.

Image from the Israel in Ghana Facebook account

Israel, Africa, and the politics of US patronage

Alex de Waal shows how some of the dynamics Israel in Africa describes meshed in Kampala earlier this year, when Netanyahu met Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the chairman of Sudan’s Sovereignty Council. For Khartoum, or at least for al-Burhan, the immediate objective was attracting American attention. But the event was also the culmination of a long process of rapprochement between Israel and Sudan, which began years before the revolution and was driven not only by Israeli but also Saudi and UAE interventions.

Long-term objectives notwithstanding, the widely publicised meeting was also part of Netanyahu’s election campaign, supposedly proving once again to opponents in Israel that his hawkish strategy does not harm Israel’s international standing but rather, can deliver “diplomatic flourishing” and normalisation with the Arab world.

We have seen a similar African attempt to benefit from Israel’s relationship with the US in the decision of DRC president Felix Tshisekedi to speak at the AIPAC conference in Washington DC in early March this year. In his speech, Tshisekedi not only emphasised his evangelical Zionist background and his support for Israel and the Jewish people, but also promised that the DRC would open an embassy in Tel Aviv with an economic office in Jerusalem. He also expressed his support for Donald Trump’s so-called “peace plan” for Israel/Palestine, announced a few weeks earlier. Tshisekedi’s speech came as a surprise, but there is a decades-long history of Congolese attempts to draw on Israeli diplomatic and business networks in order to win favour with the US.

Michael Woldemariam points out that it is not always clear that such steps result in explicit changes in American foreign policy. In Israel in Africa I have been more concerned with the way Israel’s relationship with the US impacts its leverage in Africa, and less with the consequent impact of this relationship on Washington’s African strategy. This is an issue that would, I agree, benefit from further research that examines the relationship between Israel, pro-Israel groups, African states, and the US, from Washington’s vantage point. The significance of these interactions may vary not only, as Woldemariam writes, across policy spaces, but also, at least to some extent, with changes in American and Israeli leadership.

Certainly, African hopes that showing support of Israel will persuade the US to change its policy in Africa can be misguided, and it is often difficult to identify direct causality between African moves vis-à-vis Israel and US policy vis-à-vis Africa. As de Waal writes, the Netanyahu-al-Burhan meeting was “too blatant an attempt at arm twisting to work”. To the extent that Tshisekedi’s announcement in Washington was supposed to help him secure a meeting with Donald Trump, as some have suggested, they, too, failed. But we should not disregard the very real impact the recent efforts of both of these countries to mend their relationship with the US are having on their relationship with Israel.

Medium-sized countries and the political marketplace

The question of Israel’s relationship with the US relates to another important issue Woldemariam raises in his review. He argues that one of the contributions of Israel in Africa to the field of African international relations is its focus on a medium-sized country, but also notes that this theme is not explicitly developed in the book. I agree, and perhaps it should have been. Though this is not something I had in mind when I began working on the book, I did gradually come to realise that we could certainly benefit from more research that examines how non-Western medium or even small countries manage their affairs in Africa.

In the scholarship on African international relations, whose agenda is often set in academic centres in the US or Europe, such countries are often neglected. But their interventions are not inconsequential, and as the Israeli case suggests, the way these states “work” in the continent may be very different from the way major powers do. It is therefore worth asking: what do they look like as states in Africa? What do they offer in what de Waal calls the “transnational political marketplace”? What sort of historical narratives or rhetoric do they deploy to frame their relationships in Africa?

Israel’s circumstances – its religious importance for evangelical Zionists, its relationship with the US, its occupation of Palestine, its arms industry and fragile relationships in the Middle East, its proximity to Africa – are unique. But in what ways is its experience nonetheless similar to that of other medium-sized countries, often client states of larger powers themselves, that see in Africa opportunities to advance their economic and political interests or improve their position within regional hierarchies?

Netanyahu’s state visit to Museveni in Uganda February 2020

Consider, for instance, the UAE, whose impact on African affairs, particularly in the Horn, is now widely acknowledged, or Lebanon, a state with a much smaller economy but significant diaspora in Africa, which also hosts many African migrants. Outside the Middle East, we can also think of Taiwan – another small state with a powerful security sector, embroiled in diplomatic battles that have impacted its strategy in Africa – as an interesting comparative case. There is far too little nuanced and historically informed scholarship that evaluates the interventions of such countries or their multifaceted relationships in Africa.

Bridging the Red Sea

While Woldemariam highlights that my book tells us something about how medium-sized powers influence African affairs, de Waal adds that it deals with a cross-regional relationship (indeed, one of many) often ignored due to the traditional but problematic divide between the fields of African and Middle Eastern Studies.

Though Israel in Africa does not reflect on this process in detail, one of the exciting things about writing an updated analysis of the relationship between Africa and Israel was drawing on scholarship on the politics and history of both Israel/Palestine and Africa. In this regard, I see it as a small contribution to an emerging dialogue on the relationship between these regions.

There are other conceptual lenses through which the book can be examined, perhaps less broad. When I spoke about it with Israeli students and academics in Ben-Gurion and Tel Aviv universities last month, conversations tended to focus on the ways in which it differs in its approach from earlier scholarship on Israel in Africa, with its emphasis on the role of non-state actors, the Palestinian issue and migration management.

As Seth Anziska noted in the webinar on the book, the story Israel in Africa tells can also be seen as part of a wider historical process in Israel’s international strategy, in which Africa is only one part: the “neutralisation” of the Palestinian issue, which has allowed Israel, at least for now, to develop new diplomatic relationships not only without making any effort to advance democratisation or peace in Israel/Palestine but while entrenching the occupation. How long this process can continue is a question the book leaves open.

*Yotam Gidron’s book Israel in Africa: security, migration, interstate politics was published in the African Arguments series in April 2020. Further details here: https://www.zedbooks.net/shop/book/israel-in-africa/

Israel in Africa, an African Arguments book