South Sudan’s two big foreign policy questions

Amid shifting dynamics in the Horn of Africa, South Sudan finds itself caught in the middle of regional rivalries.

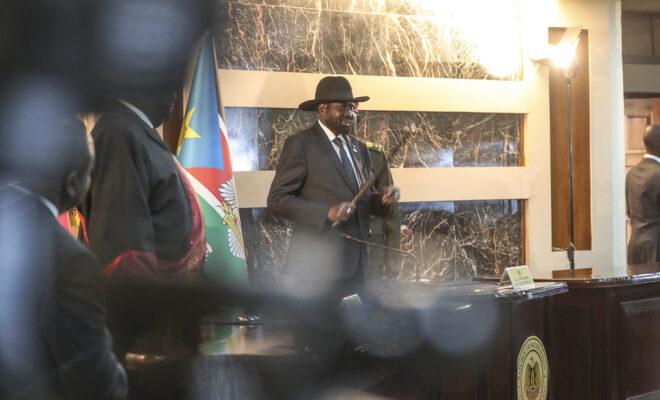

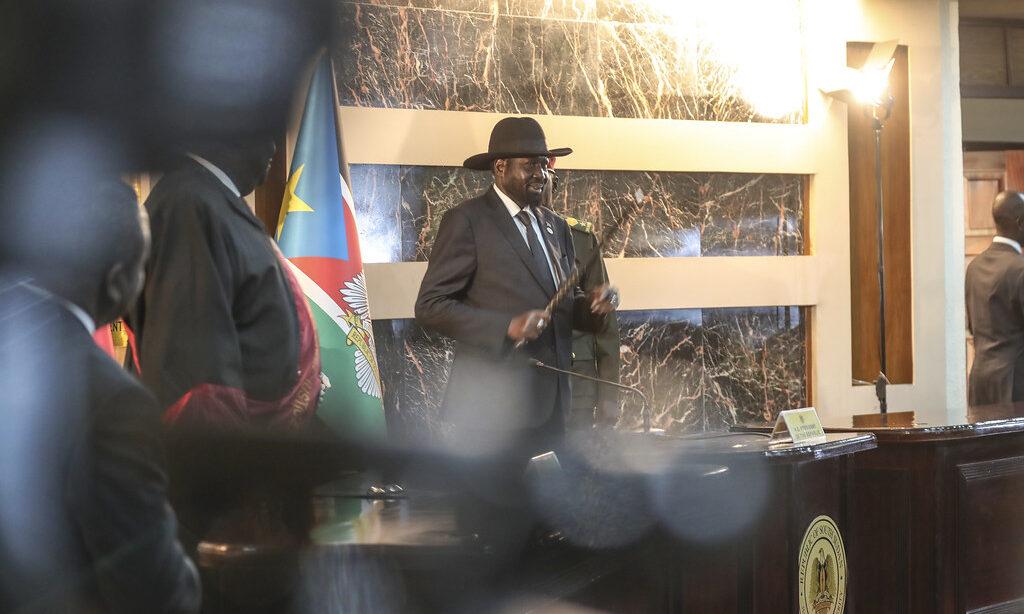

President Salva Kiir at the swearing in of South Sudan’s transitional government in February 2020. Credit: UN Photo/Isaac Billy.

On 28 November, Ethiopian federal forces claimed to have captured Mekelle, the capital of the Tigray region. This may be a decisive moment in a conflict that could shape the country and broader Horn of Africa region for years to come.

No doubt recognising this, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi was also busy that day. He flew to Juba to hold bilateral talks with South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir. The timing of the meeting raised suspicions that Egypt is exploiting its rival’s internal crisis to assert itself more strongly in the region, particularly regarding its dispute with Ethiopia over the Nile waters.

There have been plenty of changing geopolitical dynamics in the region recently. These have been prompted by a variety of bilateral rivalries, internal conflicts, changes of government and growing external influence.

For South Sudan, these shifts provide both risks and opportunities. They involve several different relationships and uncertain developments, but they ultimately present Juba with two critical decisions to make.

Uganda or Sudan?

Historically, South Sudan has tended to have a hostile relationship with Sudan and positive relations with Uganda. Before South Sudan gained independence in 2011, rebels in the south got help from Uganda in their fight against Sudanese government forces. Following independence, relations between Juba and Khartoum quickly broke down and, when a civil war broke out in 2013, Uganda again provided crucial support to President Kiir’s forces.

More recently, however, some key dynamics have shifted. In 2019, Sudan’s president Omar al-Bashir was overthrown after three decades in power. Since then, Khartoum has moved closer to the triumvirate of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt, and away from Turkey, Iran and Qatar. It is in the process of normalising relations with the West and Israel. Moreover, relations with Juba have also become much friendlier. This September, South Sudan even hosted and mediated Sudanese peace talks.

These changes have coincided with the fighting in South Sudan subsiding too. After seven years of conflict and repeated attempts at peace deals, former rebel leader Riek Machar returned to Juba this February to be sworn in as vice-president once again.

Juba’s improved relations with Sudan and the end of its civil war significantly reduces Uganda’s importance. South Sudan’s trade is likely to flow more freely northwards now, rather than through its southern neighbour, and Kampala’s influence looks set to wane.

It remains to be seen how much President Yoweri Museveni attempts to reassert his influence. Several South Sudanese elites have invested heavily in Uganda, offering him some leverage. Meanwhile, Ugandan forces attacked South Sudanese soldiers in a border town in late-October, killing two people and capturing one. This assault could be interpreted as punishment for the military cooperation agreement Juba had signed with Khartoum days earlier.

South Sudan’s government thus faces a challenge in balancing its relations with Sudan and Uganda. On the one hand, Museveni remains a powerful and historically strong partner who could provide a rear base for armed rebels if relations deteriorate as he tries to assert regional hegemony. On the other hand, closer relations with Sudan could help both countries address their security challenges and help South Sudan’s economy, which relies on oil transiting through its northern neighbour.

Egypt or Ethiopia?

The other key balancing act facing South Sudan in its foreign relations is between Egypt and Ethiopia. These dynamics have also shifted recently. Historically, southern Sudan’s rebels were supported by Ethiopia, while Egypt backed the government in Khartoum. But since South Sudan gained independence, calculations have changed.

In the past decade, South Sudan and Egypt have significantly improved relations. Egypt has increased its investment in South Sudan and provided military training to the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). A branch of Alexandria University is set to open in the town of Tonj in 2021. And President al-Sisi flew to Juba for talks with President Kiir last month.

Unfortunately for South Sudan, these links are not distinct from broader regional dynamics. Egypt is currently locked in a dispute with Ethiopia regarding the latter’s construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam upstream on the Nile river. President al-Sisi’s overtures to Juba may well be designed to persuade it to side with Egypt or at least remain neutral in the Nile politics. It may have been timed to capitalise on the possibility that Ethiopia will descend into further instability amid the civil war in Tigray.

This presents Juba with a difficult challenge. On the one hand, closer ties with Egypt could bring political and economic benefits. Moreover, Egypt’s close ties to Sudan may make it difficult for South Sudan to disappoint Cairo without upsetting Khartoum too. On the other hand, closer relations with Egypt could anger Ethiopia, a historically close partner and one that has significant support among the South Sudanese public. It is also the case that a frustrated Addis Ababa could retaliate by providing support or refuge to South Sudanese rebel groups, endangering the country’ fragile peace.

A balancing act

Recent geopolitical shifts in the Horn of Africa have created flux and uncertainty in the region. For South Sudan, this provides both opportunities and dangers. In particular, it finds itself in the middle of rivalries between Sudan and Uganda, and Egypt and Ethiopia. Relations with each of these countries could bring great political and economic benefits to South Sudan, yet each also has a history of supporting different armed forces in South Sudan and could do so again if it wanted to punish Juba or encourage regime change.

For the South Sudanese people, good relations with all four countries and neutrality in regional disputes would likely bring the most sustainable advantages. Juba could enhance this possibility by pushing for regional intervention to deescalate tensions and resolve the conflict in Ethiopia.

It remains to be seen, however, whether this kind of balancing act is one that Juba can walk and one that its partners will allow it to take.