Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

Author’s book published by Northwestern University Press.

Muslims in Kenya

Due to the diverse nature of the country, Kenya’s Muslim population is characterized by clear racial, ethnic, linguistic and sectarian fragmentation. In addition to the Arab and Indian Muslims who settled on the East African coast from around the fourteenth century, there are several indigenous Muslim groups. These include not only the coastal communities like the Swahili, the Digo, the Duruma and other Mijikenda groups, but also the Pokomo, the Taita, the Rendille and the Oromo (Borana), as well as Muslim minorities among the Luo, the Kamba and the Kikuyu among others. Today, Muslims form a minority of Kenya’s population with the majority residing in the Coast and North Eastern regions. Despite these communities being Muslims, Islamic norms have not completely replaced older traditions. This creates a complex moral field in which patterns of continuity and discontinuity regarding sexuality have to be constantly navigated.

Sex and sexuality in Muslim communities

In Islamic discourse, the importance of fertility is celebrated in the belief that procreation ensures the endurance of humanity and by extension Islam itself. As a result, sex and sexuality are understood as possible in particular circumstances and guided by specific social rules. Thus, sex is not something to be experimented with and enjoyed outside certain stipulated parameters in contradiction to the Digo Muslims female initiation practice as demonstrated below. Certain sexual taboos, such as sex with a woman in her menses, should rigorously be adhered to, in addition to sex before marriage. Marriage is an essential cultural feature in Islam because it provides the “correct” ritual context in which procreative sex is allowed.

In certain Muslim communities Islamic religion has merged with cultural customs such as the tradition of female initiation. Mohamed Suleiman Mraja’s study (2007) for instance revealed that the unyago female initiation was a popular practice among coastal Digo Muslims, which centred on female sexuality and social transformation of young girls into marriageable women. This practice, with a similar name, is also evident among certain Swahili Muslim communities in the country. Through a sequence of lectures, dances, songs, and practical demonstrations from the kungwi/somo (instructor), the mwari (initiate) was instructed on womanly conduct. Since sex education forms a central component of unyago initiation, some of the dances and rituals taught the girls issues related to sex and sexuality. During the initiation ritual dance (unyago), the young girls were initiated to skills of sexual intercourse. They learned the skill of seductively turning their hips, thighs, and buttocks to enhance sexual gratification. To master the techniques to gratifying sex, the girls also practised the skills on each other, an act that, without doubt, stimulated them sexually. Certainly, the performance exposed the female initiates to homosexual experiences. Appreciably, the dance initiation was intended to produce girls who were skilled lovers and who valued the gratification of sex as an essential component in a marriage life. However, from the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century, Salafi-oriented clerics and individual local Muslims have turned out to be strong critics of these practices because, in their assessment, they view them to be promoting lewdness (lukwale) among women.

Homosexuals: tolerated and hated at the same time

Against the backdrop of the emphasis on fertility, it is clear why perceived or self-identified “homosexuals” are hated in conservative Muslim societies. However, this presents a paradox that while on the one hand, religious doctrine sounds rather strict, particularly regarding same-sex sexuality, which seems to mostly contradict the matter of reproduction, it would be anathema with, on the other hand, the presence of same-sex sexuality. This notwithstanding, studies have shown that non-normative sexualities are practised among the Muslim communities in Kenya (Shepherd 1987; Amory 1998), in spite of the reputation of Islam for being homophobic. Among coastal Muslim communities in the country, there exist individuals who are often identified as shoga/senge, a pejorative term used to refer to “feminine” or “passive” men who engage in sexual relations with other, conventionally masculine, men. Despite the shoga contravening the gender and sexual norms of sharia, they used to be tolerated in society. It is only in recent decades, with the appearance of Salafi-oriented, Wahhabi-inspired, movements in the country that their existence has become contested and they have become the subject of persecution and ridicule. Indisputably, shoga identify themselves as Muslim, and they believe that it is Allah who created them the way they are.

In Kenya sexuality has become a deeply politicized landscape in the postcolonial period. To demonstrate their rejection of what they perceived as the increasingly liberal sexual culture of Western societies, endorsement of heterosexuality in the postcolonial time became connected with “African culture” and “African values”. In more recent decades, this resistance has become most evident in the open campaign against gay rights, which are widely depicted as “un-African” and depending on the context, as “un-Christian” or “un-Islamic”. The coining of the latter expressions demonstrates how both Christianity and Islam have been exploited in the politicization of sexuality in the country, in order to promote an inflexible heteronormative culture.

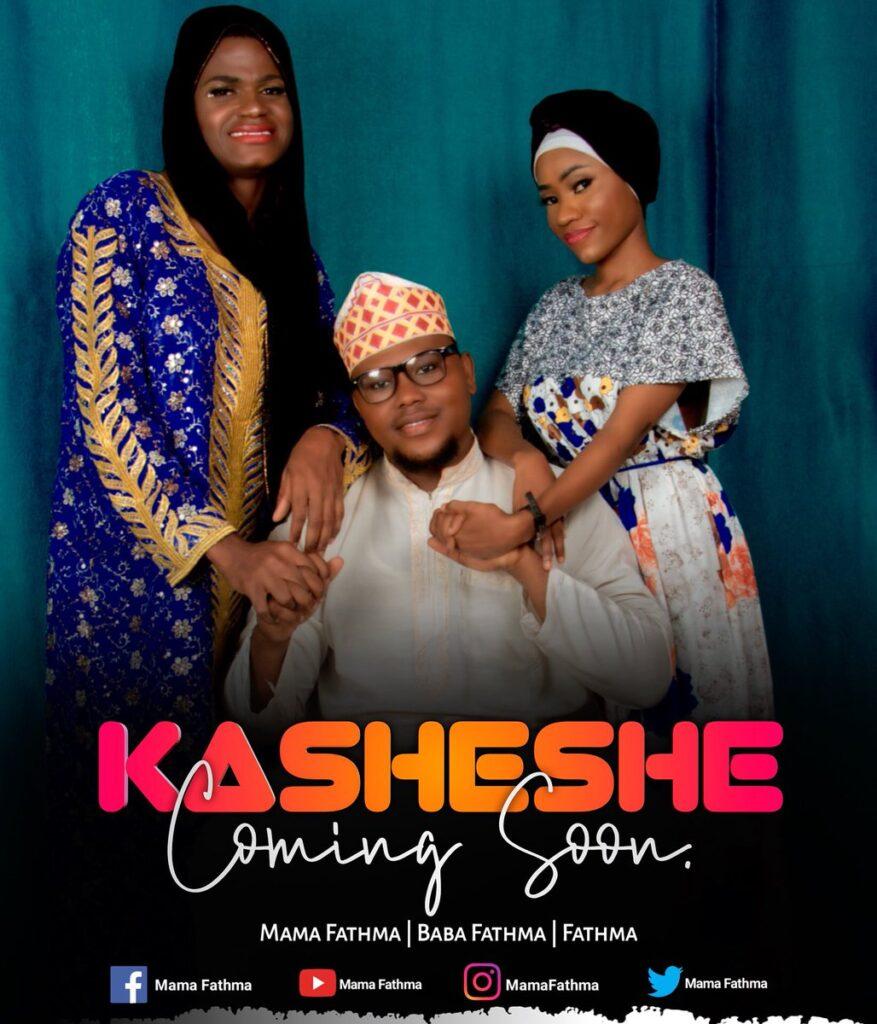

“Mama Fathma” the alleged gay comedian

In this last section, I would like to highlight “Mama Fathma”, a coastal based online comedian mainly found on YouTube who uses his performing art skills to portray his supposedly homosexual orientation.[1] Mama Fathma’s real name is Idris Salim Kidogo, a young man in his earlier twenties who began his acting career around 2018. He created the character Mama Fathma to depict a coastal based woman who goes through several life experiences typically associated with coastal women. While he has attracted a large fan base, Mama Fathma has also been attracting hate in equal measure. While commenting on his YouTube performance circulating in a WhatsApp group, one member complained, “My opinion is we desist from circulating this guy.… He is busy promoting LGBTQ activities and slowly getting into our homes to our children and wives under the guise of comedy.” In the same platform other comments expressed, “whenever I see the stupidity of this senge [homosexual], I usually delete before playing it … and then some women defend him saying we should not judge him. Nkt! Very stupid guy … he is insulting men.” Clearly, the comedian is bashed for allegedly not being straight thereby urging him to stop being gay. Although it is not obvious that a man performing a woman’s role should necessarily be perceived as “gay”, in this coastal Kenyan Muslim community he has judged to be so.

Similar vitriol directed at the comedian has been expressed by a section of Muslim clerics alleging that Mama Fathma was flouting Qur’anic teachings. Sheikh Aboud Mohammed, an imam of a local mosque in Mombasa, criticized Idris for wearing female attire on the pretext of acting and instead urged the comedian to cease acting his opposite gender. “We all know it is against our religious norms for people to force themselves in their opposite sex, this is unacceptable,” the imam warned. “A Muslim young man putting on bra, ladies panties and dresses in the name of comedy costumes, this is not allowed in our religion,” lamented another Muslim cleric. What seems to infuriate his critics is his “girly” gender performance. In the opinion of the Muslim clerics, Idris should perform his act as a man and not a woman to avoid contradicting the supposedly Islamic teachings. While responding to the religious leaders and other critics, Idris maintained that he is just a comedian who is striving to earn an honest living through performing art, and the character Mama Fathma is not his true identity.

In an interview, he lamented that, “Even my Muslim brothers condemn me saying I embarrass them”, and perhaps in an effort to prove them wrong he declared to be engaged, but when probed further to reveal the identity of the woman he refused. Arguably, it is possible that Idris’s insistence that he is soon to be married is merely to conceal his sexual orientation. And more so, according to a hadith attributed to Prophet Muhammad: whoever marries achieves half of their religion, which perhaps is what Idris is keen to fulfil. It is common for non-openly gay and passive male homosexuals amongst coastal Muslim communities to marry a woman but secretly continue engaging in non-normative sexual behaviour. If Idris’s detractors are right that he is gay, being in a Muslim marriage is not a choice for him, but a religious responsibility for procreation, and this is why he is expected to “have sex with women” for procreation purposes “and not necessarily for sexual pleasure.” Apart from acting, Idris disclosed that he loves cooking, which he occasionally does when hired for a fee. These feminine gestures and performance of tasks associated with women (cooking and selling food) are behaviours that are also exhibited by gays according to Amory’s study.

Without doubt, the creative and communicative skills presented by Mama Fathma through performative art have raised a lot of debate in Kenya’s Muslim public sphere. What could be deduced from this debate is: (i) that crossing of gender boundaries, even for entertainment purposes, is harshly castigated in Muslim societies, (ii) that, exactly because of his art being seen and dismissed as “homosexual”, his performances give some (contested) visibility to people who are otherwise discriminated against, excluded and marginalized because of their sexual orientation; and (iii) that, whether or not Idris self-identifies as “gay”, it is possible that his performances give him a platform to experiment with and express some gender and/or sexual dissidence without fear.

End Note

[1]A sample of Mama Fatham videos see, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5KS0Q8hknI; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpAV-EYFFWQ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PAjc6pOLFyE).

References

Ali, Haramo. 2020. “Mama Fatma” comedian scoffed for disregarding Islamic teachings. Jambo News Network, https://www.jambonewsnetwork.com/lifestyle/entertainment/mama-fatma-comedian-scoffed-for-disregarding-islamic-teachings/.

Amory, Deborah P. 1998. Mshoga, Mabasha, and Magai, “Homosexuality” on the East African Coast. In: Boy-Wives and Female Husbands, eds, Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe. New York: Palgrave.

Grillo, Laura S., Adriaan van Klinken and Hassan J. Ndzovu. 2019. Religions in Contemporary Africa: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

Loimeier, Roman. 2018. Islamic Reform in Twentieth Century Africa. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Mama Fathma interview, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxxwe7WcIOo.

Mraja, Mohamed Suleiman. 2007. Islamic Impacts on Marriage and Divorce among the Digo of Southern Kenya. Wurzburg: ERGON Verlag.

Ndzovu, Hassan J. 2019. Islam in Africa South of the Sahara: The Status of those with Non-Normative Sexual Identities in African Muslim Communities. In: Howard Chiang et al., eds, The Global Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) History. Farmington Hills, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Ndzovu, Hassan J. 2016. “Un-natural”, “un-African”, and “un-Islamic”: The Three Pronged Onslaught Undermining Homosexuals Freedom in Kenya. In: Religion and the Politicization of Homosexuality in Africa, eds, Adriaan van klinken and Ezra Chitando. New York: Routledge.

Shepherd, Gill. 1987. Rank, Gender and Homosexuality: Mombasa as a Key to Understand Sexual Options. In: The Cultural Construction of Sexuality, ed. Pat Caplan. London: Routledge.

https://cialiswithdapoxetine.com/ cialis 20mg

cialis without a doctor prescription cialis price