Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

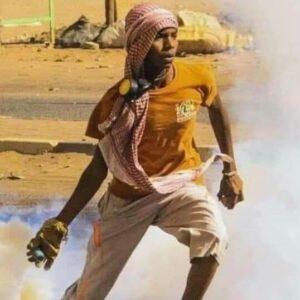

Hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of demonstrators marched across Sudan yesterday, 30 October, against Sudan’s military coup. As of this morning, eleven people were reported killed and perhaps more than a hundred were injured.[1] Here are three takeaways from the demonstrations.

Al-Burhan’s political proposal is not viable without repression

The tremendous outpouring of non-violent demonstrators across Khartoum and Sudan show that military commander Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan’s announced government is not realistic. In his 26 October address, al-Burhan proposed a new technocratic government that he selects. Al-Burhan has also tried to persuade Abdallah Hamdok, among other civilian candidates, to return as Prime Minister in what would be a potemkin cabinet. But the impressive size of demonstrations detail how al-Burhan’s total military takeover is not going to be possible without crushing the protest movement through repression and violence.

A key reason why al-Burhan’s political proposal is not possible is partially because he has no political constituency. Unlike Omar al-Bashir’s military takeover in 1989, al-Burhan is not governing based on ideology. Al-Burhan has no political constituency either. And unlike the 2013 Egyptian coup, civilians have not aligned with the military takeover but instead are overwhelmingly against it. Al-Burhan’s options are either repression or compromise with civilians. Yet it will become more apparent to al-Burhan’s core pillars of support – the coup-quartet and the senior commanders around him – that the SAF commander is not quite the political savant and that another military leader would be able to negotiate better terms.

This is not a well-planned coup

The Egyptian military coup in July 2013 was well planned. The army announced specific deadlines to the Morsi government for days. When Abdel Fattah al-Sisi announced the coup he also presented a transitional leader. In contrast, Sudan’s 25 October military coup appears slapstick. As of Sunday morning, al-Burhan is still struggling to name a transitional Prime Minister nearly a week after the takeover. There is little evidence that al-Burhan is attempting to build a coalition to govern.

Al-Burhan’s justification for the coup and detaining Prime Minister Hamdok for his own safety has been met with mockery online. As much as anyone in Sudan, it appears al-Burhan is unprepared for the takeover he executed. A key inference in this delay and bizarre justification is political mis-calculation from al-Burhan. The failed creation of the FFC-2 and manufactured palace sit-in garnered nearly no support and should have been a sign that their takeover would not be popular with people.

What does the lack of preparation and mis-calculation mean? Al-Burhan’s days may be numbered as military leader.

The coup has re-united the civilian movement

Just over a month ago, Hamdok’s popularity among the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) and Resistance Committees was barren. Around half of the unions in the SPA had called for Hamdok to resign as Prime Minister. The other half were similarly frustrated with Hamdok but were wary of calling for his resignation because there was no alternative to his leadership. Many Resistance Committees had a similar sentiment. But in yesterday’s protest across Khartoum there were dozens of signs bearing Hamdok’s image. It is difficult to calculate the extent to which Hamdok’s popularity has rebounded among protestors, but Saturday’s protest is evidence that this coup helped, rather than hurt the Prime Minister. How will Hamdok use this new popularity? The Prime Minister governs by consensus rather than by mandate, meaning he may still seek a compromise with the military. That might frustrate the SPA and Resistance Committees, once again. Another key indicator of the consolidation of the civilian movement is the reemergence of Mohamed Nagy Alassam, who was a key leader in the SPA before the body split. Internal rifts within the SPA have also been papered over, for now.

End Note

[1]Sudan Central Doctors Committee, 30 October 2021, twitter.com/sd_doctors_status_1454492668388319233?s=21 (figures updated from 3 to 11 since).

————————————

“This Is Not a Coup” is a daily update from Sudan that gives perspective on the country’s military takeover. The author is anonymous to protect their identity. The title is a reference to the 26 October speech of General Abdel Fatah al-Burhan.