The Sudan Crisis viewed from Juba: A path towards resolution

Given their strong historical bonds, and Juba’s track record, what is the argument for Juba to mediate the conflict in Sudan?

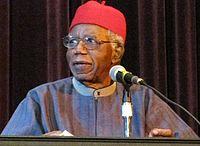

President Salva Kiir Mayardit meets Sudanese military leader, Gen. Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan in Juba, 19 February 2023. (Photo courtesy: Office of the President, Republic of South Sudan).

With over 500 indigenous African ethnicities, Sudan is necessarily founded on its ethnic diversity. Despite its wealth of human and natural resources, however, it is at a crossroads. War, a constant feature for many of these groups that occupy the periphery, has, after 67 years, arrived in Khartoum. Ironically, this is where it has always stemmed from.

The root cause of Sudan’s crisis is the country’s conflicted identity, which produced the system of privilege and exclusion concentrated in Khartoum, the nation’s capital. The imbalance of power, favouring the country’s three self-proclaimed Arab riparian ethnic groups over many others, has created a rift between privileged and marginalised groups, triggering a cascade of conflicts.

The power dynamics in Sudan led to the war in the South, but the Khartoum power structure refused to address the root causes. Instead of addressing the fundamental issue, the partition of the country was viewed as a solution, leading to the secession of the South. It’s not surprising, therefore, that the war has extended into the North, with the Army using paramilitary forces to suppress ethno-regional discord in Darfur, the Nuba Mountains, the Blue Nile, and other regions.

This approach, driven by the persistent failure to tackle the core problem, now risks fragmenting the country in a manner reminiscent of the Balkans; those same paramilitary forces, armed, organised, and deployed by the government, have now turned on their paymasters stating that they have understood and now champion the cause of the marginalised ethnic communities.

So what is the alternative to Sudan’s balkanisation? A genuine commitment to resolving the fundamental issue. Yet, the inability of international actors to facilitate a resolution, driven primarily by their narrow interests, remains a significant obstacle. It is in the interest of Sudan, the region, and the world to assess honestly the current state of play by the international actors claiming to help Sudan in its time of greatest need.

The undeniable fact remains that South Sudan, steeped in a shared history, culture, and context with Sudan, is uniquely placed to contribute to a viable resolution to the crisis. South Sudan’s successful brokerage of the Juba Peace Agreement demonstrates this position. Nevertheless, it is lamentable that South Sudan’s potential has been overlooked, not least by Washington, whose role both overtly and surreptitiously in brokering peace deals in the Sudans cannot be exaggerated.

The Jeddah Peace Process, brokered by the US-Saudi alliance, exemplifies the global attention directed toward the ongoing Sudanese conflict. Despite its good intentions, the initiative reveals a fundamental lack of understanding of Sudan’s core issue, creating deficiencies that could potentially undermine its success.

International interests and the exclusion of immediate neighbours like South Sudan, who have a deeper understanding of the Sudanese context, compound these challenges. Case in point: six proclamations for a humanitarian cessation of hostilities have been made since the outbreak of fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), none of which have been respected or implemented.

Notwithstanding their geopolitical interests, regional blocs like IGAD may encounter similar roadblocks due to their limited understanding of Sudan’s fundamental problem. Dependence on foreign resources further impairs their independence, engagement, and relevance to Sudan’s reconstruction.

In this context, the Republic of South Sudan, led by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) under the leadership of His Excellency Salva Kiir Mayardit, President of the Republic, emerges as a credible mediator. Our understanding of each other, the absence of ideological, territorial, or resource ambitions, and mutual strategic interest in regional security and economic cooperation position us uniquely to help navigate this crisis.

The “New Sudan” vision, created by the SPLM, fosters inclusivity, accommodating both centre and periphery, a crucial requirement for Sudan’s democratic reconstruction. It is worth noting that the Government of South Sudan promptly stepped in following the ousting of President Omer Hassan El-Bashir in 2019. Unfortunately, Western allies favored the African Union’s involvement over ours, creating the Sovereign Council and the Constitutional Charter. The latter, lacking clear power-sharing safeguards, indirectly led to the October 2021 coup.

The Juba peace initiative, launched by the South Sudan Government, aimed to foster dialogue between the Transitional Government of Sudan and the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF), a conglomerate of various armed and unarmed movements. This innovative political process established the Juba Peace Agreement. This groundbreaking document addressed the heart of Sudan’s ongoing discord, offering a blueprint for democratic reconstruction across all conflict regions.

Don’t miss a thing. Sign up to the free African Arguments weekly newsletter.

Our initiative led to a meaningful step towards stability; yet, on 25 October, 2021, the military staged a coup, dissolving a promising civilian government. The aftermath saw the reappointment of a civilian Prime Minister, reduced to little more than a figurehead under the watchful eye of the military junta. However, the junta, under Al-Burhan, recognised the objectivity of the Juba peace agreement. This agreement, rather than emphasising a power-sharing deal, established a robust framework for the post-conflict democratic reconstruction of the country.

Before the onset of the war, attempts to restore civilian rule faltered. Western allies seemed to favour some Western-leaning parties in the civilian coalition more than others, fostering division rather than cohesion amongst the parties. This inequity was due to a peace process spearheaded by inexperienced mediators unfamiliar with Sudanese political intricacies.

Despite being pushed out of direct mediation, South Sudan’s persistence in resolving the Sudanese conflict was manifested in the Juba Peace Agreement, showcasing the strategic position and the potential we possess in helping to address Sudan’s root problem.

The tale of Sudan is thus one of struggle and turmoil but also one of hope. A new chapter awaits, and it requires recognising and addressing the fundamental issues that have led to its present condition. We believe in the capacity of South Sudan to play a unique role in achieving this end, guided by our shared history, deep contextual understanding, and mutual respect for all parties involved.

I have recounted the story of Sudan as seen from the eyes of someone at the heart of its political and diplomatic engagements. This narrative, I believe, is a guide along the path toward a peaceful resolution to finally address the fundamental problem of Sudan once and for all.

Thanks for sharing the analysis of Sudan’s conflict by Mayiik Ayiik Deng. He has reached similar analysis on the issue of identity as Prof. Suleiman Mohamed Suleiman in his book “The Sudan: Wars of Identity and Resources” that was published in London around year 2001 in Arabic. Prof. Suleiman hailed from Darfur, one of the neglected areas in Sudan.

However, late Ambassador Bethuel Kiplagat of Kenya went deeper in classifying the identity issue in terms of Arab racism but within the black colour. Late Ambassador shared his findings with the SCC after attending a workshop in Khartoum organized by Northern Sudanese women before separation of South Sudan. I was still serving as General Secretary of SCC from May 1995-May 2003. Late Amb Kip told us that he asked the Arab women whether there was a colour problem in Sudan during the workshop. That the women at first kept quiet and then opened up by admitting indeed there was a colour problem in Sudan. Then late Amb Kip asked his second question as to the number of colours and hierarchy. That the women stated that the colours were four: red (humur), light(fatih), green (Kudhur) and blue(zuruk). Then he asked where the women fell in each colour. The answer was that the women follow the colours of the men in each colour category. Then late Amb. Kip asked for identification of the Sudanese men and women based on those four colours. The answer was that the red people are the Arabs ( Jaalin, Shagia and Danagila), the light skin people are the Halafawiin, the green people are the Darfurians and the blue people are the Southern Sudanese. That when you add the women, they will fall under each colour.

It was quite a revelation to us to learn that we Southern Sudanese men were in the seventh class and our women were in eight class based on the findings of late Amb. Kip. Thus for the first time we became first class citizens after our separation in July 2011.

Based on the above, one cannot see how the Arabs tribes will accept to unity in diversity of the remaining colours: red, light, and green people of Sudan? May be they need to borrow a left from South Africa after defeat of Apartheid rule in 1994 by ANC and the Churches.

Regards,

Rtd Bishop Enock Tombe

Dear Editor

This is one of the thought-provoking piece ever on the current stalemate on the resolution of conflict in Sudan. As stated by the author ” The root cause of Sudan’s crisis is the country’s conflicted identity, which produced the system of privilege and exclusion concentrated in Khartoum, the nation’s capital. The imbalance of power, favouring the country’s three self-proclaimed Arab riparian ethnic groups over many others, has created a rift between privileged and marginalized groups, triggering a cascade of conflicts”.

This complex situation is well understood by South Sudan and the leadership , considering longstanding historical ties between the two countries

Dear editor

Thank you for sharing the article of Hon. MAYIIK AYII Deng the former Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of the Republic of South Sudan. The author of the article has highlighted the fundamental political problems affecting Sudan.However, the article is written by a person who is well versed with the current political crisis of Sudan.

This article can be used by parties to the conflict and mediators to help them find permanent solution to the current crisis in Sudan.

Given the shared history between South Sudan and Sudan; South Sudan government and its leadership can play a positive role to help the parties to the conflict in Sudan to find a sustainable political Solution to the current conflict in Sudan.

The author of the article has done a good job in highlighting the fundamental political issues that are affecting Sudan.

Regards

Amb. Deng Obed Madol

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on the conflicts in Sudan.

However, the president Kiir Mayardit should help our people in Sudan to reach peace.

In this critical time of war in Sudan, South Sudan should stand up supporting their brothers and sisters in Khartoum for the fact that we are all Sudanese people.

As a concern citizen of South Sudan and Sudan, I am requesting our leaders in Juba to Push the warring factions to reach peaceful settlement in Darfur, Nuba, Blue Nile, Khartoum and Eastern Sudan. We must learn how to forgive our brothers and bring them peace.

Ever wishing them God’s blessings

Bok Yieny Bok

Prime Resident

Rumangok Areas Chieftaincy & Integrated Villages’Administration

I thank you for sharing the article on this web.

I believe the idea of giving regional countries the chance to mediate the worrying parts is a practical issue, as the conflict affects them directly and indirectly, hence they could play a significant role to resolve the matter for the benefit of all. South Sudan could play its role as stated by the writer because of its knowledge and history, however, I think IGAD as a regional organization must play a leading role. We should not forget that the Republic of Sudan shares borders with several member states.