A letter from Ghana – “˜Homos’ and Hysteria: reporting the gay debate in Africa – By Clair MacDougall

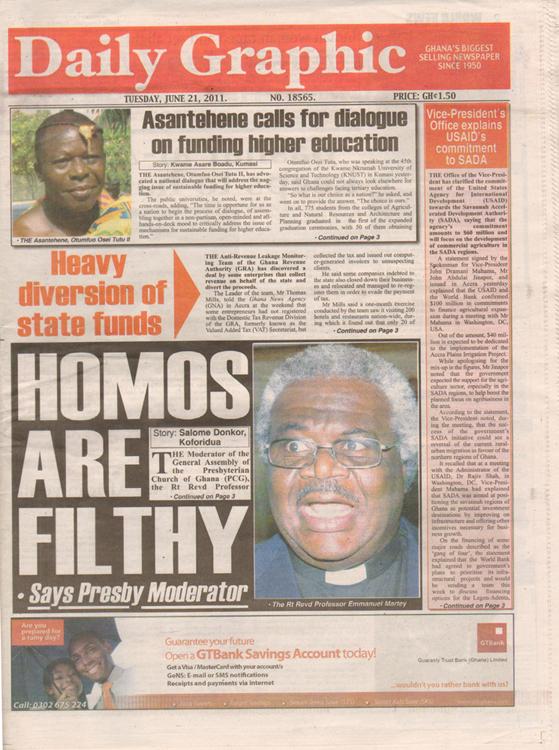

One morning back in late May, I stumbled up the street to buy my morning paper. I opened the paper to find a headline that read:

One morning back in late May, I stumbled up the street to buy my morning paper. I opened the paper to find a headline that read:

“˜8,000 Homos In Two Regions: Majority Infected With HIV/AIDS’.

I looked up at my local newspaper vendor, a jovial old woman sitting behind a square, wooden table.

“What do you think about this?” Pause. “What do you think about gays?”

“Oooooh! I hate them!” she said.

Not an uncommon view here in Ghana, or across the African continent.

The particular story I had read that morning sparked a heated national debate about the moral and social acceptability of homosexuality in Ghana. The article quoted figures allegedly released at a conference held by USAID and was followed by a series of sensational stories in local newspapers and media outlets, with each headline more melodramatic than the last.

The issue reached a crescendo and made international headlines when Minister for the Western Region Paul Evans Aidoo on national radio called for all gays and lesbians to be arrested. The statement was made just days after the Ghana Christian Council called for a national “˜crusade’ against homosexuals.

The main concern expressed by community leaders and the general public is that gays are invading Ghana and spreading homosexuality – consequently attacking both Christian (and Islamic) religious values and African cultural sensibilities. But there is more to this issue than a few dramatic sound bites and a rather complex subtext to these condemnatory statements.

After recently speaking with African gay activists and academics about what they viewed as sensational and oversimplified reporting by Western journalists on the issue of homophobia in Africa, I thought it a good idea to write about the challenges Western reporters face and the ways that we can report on the issue in a more nuanced way.

I have found reporting on the backlash in Ghana challenging on a number of levels. Reporting on such a sensitive issue is a difficult task for any journalist trying to navigate their way through a new culture and cosmology (while also attempting to avoid being labeled an “˜imperialist reporter’ in Africa). Looking at the broader meaning and subtext that underlies the comments of others, a common practice for any reporter, draws attention to the complexity of issues, but it can also suggest that subjects are unable to fully represent themselves and articulate their opinions. However, digging deeper, moving beyond these surface level statements is the only way that journalists will get to the crux of this issue.

The “˜gay debate’ as it stands in the West is largely defined by the liberal democratic cultural and political values that are inevitably a reference point for Western journalists. While anti-gay groups in Western countries are represented in stories for the sake of balance and insofar as they have sway, liberal values and understandings of individual human rights frame the debate the journalist captures and creates within a story. The principles of Western liberalism are based upon the assumption that people ought to be free to do as they choose insofar as they do not harm others.

In many African countries, even countries with liberal democratic forms of government and institutions, a more communal understanding of social identity dominates. In a recent interview with Godwyns Onwuchekwa founder of Justice for Gay Africans – a London-based lobby group comprised mainly of gay Africans, he told me that journalists must understand fundamental cultural differences.

He suggested that the African notion of community and a strong emphasis on family poses major challenges to the advancement of gay rights.

“African cultures and black cultures are not built around people but communities, while anything to do with identity is connected to individuals,” Onwuchekwa said. “Being gay is a very personal issue that involves someone wanting to identify themselves as something and the community often stands against it.”

But appeals to cultural difference can also be problematic and deceptive and cannot simply be taken at face value. As anyone reporting in Africa will know, the notion of “˜culture’ can be used to veil blatant power and domination, and only a writer who is well versed in the nuances of a culture can draw the distinction between beliefs that are sincere and those that are expedient or manufactured.

The most common response that I have heard from Ghanaians questioned about why homosexuality is morally unacceptable, is that “˜it is not part of Ghanaian culture’ or “˜it is not part of African culture.’ However, this response implies that there is a universal consensus on what being Ghanaian or African is and means. But as most Africans and Ghanaians are themselves aware, the continent is filled with multiple tribes, clans and subcultures, with diverse social, political values and kinship structures. The idea that there is universal consensus on what is sexually permissible or acceptable is a fallacy.

Marc Epprecht – a professor in the Department of Global Development Studies at Queen’s University – has written extensively about the history of gender and sexuality in Africa and challenges the idea that the continent has a uniformly heterosexual culture. Epprecht has suggested that historically there have been a range of sexual identities and relationships in Africa, and that the notion of a uniform heterosexual identity was in part inherited from the colonial era.

In a recent column for the Royal African Society Epprecht criticises the Western media’s sole focus on the demagogy and dramatic expressions of homophobia in countries like Uganda and says there ought to be more of an emphasis on gay and queer activism and communities across the continent.

“My view is that Western reporters tend to seize on these bad news stories and give them more legs than they actually have,” Epprecht said when I spoke with him. “They get a hold of the issue and they tend to inflate it.”

Epprecht also argues that journalists must be cautious about depicting Africans as bigoted and uncivilized and look beyond the hateful statements and towards some of the broader socio-economic factors at play.

“Journalists must be wary about depicting Africans as uncivilized or somehow behind the West which is assumed to be the paragon of virtues and the pinnacle of human rights achievements,” said Epprecht.

But again, this poses a challenge and requires us to move beyond the sometimes violent claims of those who deny rights to gay people and who are often the most dominant voices in the debate. But are these angry statements not simply expressions of bigotry and prejudice? And how can one determine the broader social, political and economic issues that are feeding into the debate?

I do not think there is a definitively right way of reporting on this issue, but these are questions that journalists ought to be asking because issues that evoke the response that I have seen in Ghana rarely develop in isolation.

In Ghana there have been backlashes against the gay community before, but the most recent uproar originated in the Western Region, an area of the country that is experiencing significant socio-economic upheaval. The Western Region is expected to profit from the development of the Jubilee deepwater oilfield that began production in December last year. Many Ghanaians anticipate that the oil discovery will change their fortunes, and as President John Atta Mills said during the commencement of production that it could transform Ghana into a “˜modern industrial nation’.

Back in May, The Ghanaian Times published an article on a conference with a long and telling title: “˜Empowering cultural institutions and industries to mitigate the effects of foreign culture in Ghana in the era of oil exploitation, the role of stakeholders’ held in Sekondi, near Takoradi, the coastal city closest to the oilfield.

At the conference the Times reported the vice-president of the Western Regional House of Chiefs expressed concerns that homosexuality and lesbianism were “˜fast gaining roots in the Western Region, due to the influx of people with different backgrounds as a result of the oil discovery.’ The article continued: “˜He said the emergence of homosexuality and lesbianism in the region was posing much worry to the chiefs and people of the region, and, therefore appealed to the security agencies and all well-meaning Ghanaians to help check the practice.’

Since this conference, religious and community leaders and citizens have protested in Takoradi against what they see to be a rise in homosexuality within their communities. In many ways the backlash against gays appears to be a manifestation of fears of foreign corporate exploitation and cultural domination.

The overall causes for the recent upsurge in homophobia in Ghana are difficult to determine, but it is clear that the church is trying to assert political muscle and national media have been creating a sensation from the story. The Daily Graphic appears to have been running a public campaign and has been making front-page stories based upon the comments of anyone willing to make the loudest and most controversial anti-gay statements, regardless of their position of influence.

Reporting on the backlash against gay communities in Africa may be as difficult for Western journalists as it is for many Africans to discuss. But this is an issue that must be further explored as foreign reporters, myself included, are only just scratching the surface. Journalists must move beyond the sensational headlines and easy angles, in order to more fully represent the issue and help further the debate.

Clair MacDougall is a journalist who is currently based in Accra, Ghana. Her article “˜Rainbow People of God’ which focuses on the backlash against the gay community in Ghana features in this month’s edition of BBC’s Focus on Africa Magazine. She blogs about Ghana and West Africa at North of Nowhere.

The overall causes for the recent upsurge in homophobia in Ghana are difficult to determine, but it is clear that the church is trying to assert political muscle and national media have been creating a sensation from the story.

Why don’t you find your courage and then come back and try again.

The upsurge of homophobia all over Africa is directly proportional to the growth of evangelical (fundamental) Christianity. More than ten years ago. Robert Mugabe stated that gays should be killed. It made some noise, and in fact, I hear homosexuals are treated brutally in Zimbabwean jails, but it hardly became the source of year-long headlines and parliamentary bills like it has become in Uganda etc. These American pastors who are watching the erosion of any moral standing they have in America have exported their gay bashing to Africa just as they exported their prayer “miracles” etc. The difference is that, as Evangelicals grow in Africa, every other religious group does what it has to to itself keep growing or hold onto its flock. Go figure.

Great thoughtful piece

“However, this response implies that there is a universal consensus on what being Ghanaian or African is and means. But as most Africans and Ghanaians are themselves aware, the continent is filled with multiple tribes, clans and subcultures, with diverse social, political values and kinship structures. The idea that there is universal consensus on what is sexually permissible or acceptable is a fallacy”. the above argument doesn’t wash.

there is a near universal consensus that incest is morlly wrong. Both the west and Africa seems to agree. why is then that when Africans from Kenya, Malawi or south Africa , agree that homosexuality is wrong they are cast as not accomodative of an individuals right to chose.

this freedom to chose isn’t absolute, it can never be! it must fall within the realm of what is morally permisive by the society. remember this definition of what is morally permissive , has being the African constitution before the coming of colonialist. and as much as we have written constitutions now, the african way of life remains a source of law i n my country Kenya, thus never will this country pass a gay law.

Just to put the ‘international gay debate’ into perspective, I think it might be interesting you read ‘Desiring Arabs’ by Joseph Massad. Just so you know that ‘gay rights’ are not everywhere considered ‘universal rights’. But that does not mean gays can’t be part of the community – just not as ‘proud’ as in “Western” nations.

Firstly the writer is correct in writing that there is no universal conception of what is african and neither is there an African conception of sexuality, africa is a terribly complicated place .As a Kenyan I vehemently disagree with petro that all kenyans are against homosexuality, I am personally for rights, and I include “gay rights” in my conception of human rights and I know many kenyans who do.

Secondly morals change over time, 50 years ago you would have been laughed at for thinking about a black US president, gay rights were not even conceived of, interracial marriage was reprehensible I could go on. I think over time we shall see morals and society chang, maybe not to the point of gay marriage but a state of live and let live

Jacob Zuma, who presides over a country that arguably has the world’s most progressive constitution, appointed an anti-gay hatemonger–Jon Qwelane–as South Africa’s ambassador to Uganda, the world’s epicenter of the most heinous politicians and rabid evangelical kooks. (The strange thing I find about Uganda is that their kings were traditionally bisexual, or so we were told in our Catholic schools in the Congo: that’s why we have the whole lineup of the Martyrs of Uganda, those young men who had refused to yield to one of those kings’ sexual advances–and hence, got burned.)

In 2010, Bingu wa Mutharika, the president of the banana republic of Malawi, exclaimed:

There you go: “we Malawians”–an extraction of an essence from millions of people who’ve got nothing in common. One would’ve thought that after Jean-Paul Sartre such essentialism would have already died its quiet death.

Bingu was making this stupid statement when his country was facing worldwide outrage over the wrongful imprisonment of the newly (illegally) wed Steven Monjeza and Tiwonge Chimbalanga, who were copiously jeered by frenzied crowds at each one of their court appearance: they were facing charges of engaging in “unnatural sexual acts.” (All these hatemongers are closeted gays, as the cliche has it.)

I was in Kinshasa last year watching a live TV broadcast of a parliamentary session. And an MP, who also doubles as an evangelical pastor in his spare time, wanted to introduce a Uganda-like bill against so-called “unnatural sexual acts.” The man was copiously booed and his crazy scheme shelved.

In Kinshasa, gays and lesbians are left to their own devices–and lead normal lives. There are even some who dress in women’s pagnes in broad daylight. No newspapers to go after them; no politicians to campaign against them; and no evangelicals to persecute them–except that one crazy evangelical MP… And one more thing: most gays in Kinshasa “pump iron”; any attempt at assaulting one of them would result in mayhem!

Perhaps there’s something to the suggestion that we oughtn’t supply too much oxygen to the stories of hatred, and allow those promoting this bigotry to claim their struggle as being one of social values against foreign vices. The East African littoral has for example been able to accommodate both a passionate Islam and liberal sexual attitudes, it does not seem to me clear that this cannot grow to be the case elsewhere.

The greater danger comes when powerful politicians or institutions, like the Ghanaian politicians and institutions above, Malawi’s President, President Mugabe or Kenya’s Prime Minister Odinga make public calls for punitive action against homosexuals and present this as a state position. This endorses extremists and gives cover of law and impunity to those (even if in small minorities) who’d want to commit violent actions against sexual minorities.

Even when it offends local norms, I cannot see that there’s any possible response then but to make a very loud fuss.

“My view is that Western reporters tend to seize on these bad news stories and give them more legs than they actually have,†Epprecht said when I spoke with him. “They get a hold of the issue and they tend to inflate it.â€

Which is exactly what you do in this article although you purport to bring a balanced view to the deabte. How many newspapers are there in Ghana? Yet you choose to display the one that portrays Africans as “bigoted and uncivilized”. The newspaper headline and picture says more than the ‘thousand’ words in your article. Nuf said.