Niger and Gadaffi – fallout out from the Libyan crisis: ‘We have no means to close the border… It is too big’ – By Celeste Hicks

Until last week, Niger’s main pre-occupation was the consolidation of democracy following peaceful elections in February. President Mahamadou Issoufou was determinedly continuing with an energetic anti-corruption drive in the face of an alleged coup plot back in July. This was a big enough job. There must have been some in the government who had one anxious eye on that notorious northern frontier – a place where Tuareg rebellions, AQIM fighters and more recently armed exiles from Libya rub shoulders – but it seems no-one predicted how quickly Niger would be flung into the spotlight.

Until last week, Niger’s main pre-occupation was the consolidation of democracy following peaceful elections in February. President Mahamadou Issoufou was determinedly continuing with an energetic anti-corruption drive in the face of an alleged coup plot back in July. This was a big enough job. There must have been some in the government who had one anxious eye on that notorious northern frontier – a place where Tuareg rebellions, AQIM fighters and more recently armed exiles from Libya rub shoulders – but it seems no-one predicted how quickly Niger would be flung into the spotlight.

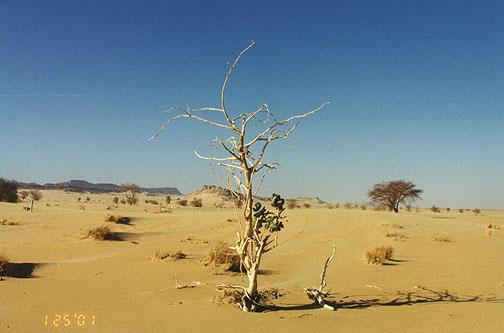

Lost souls from the Libyan conflict have in fact been wandering over the border for the last six months – the International Organisation for Migration says that it has helped over one hundred thousand Nigeriens to return since February, most of them overland. Some of them have simply vanished with the spoils of war into the vast desert. And why not? The route from Sebha in southern Libya, veering westwards along the southern tip of Algeria, and then south to Arlit and Agadez is a well-trodden Saharan path. Many of the West African migrants attempting to reach Europe set off from Agadez and go in the other direction. The border with Algeria and Libya is just a line in the sand, and Niger lacks the resources to police it.

Until very recently, Niger seemed to be thinking that security in this area was improving. In August the government announced that it was suspending military escorts for humanitarian agencies travelling to the north. The MJN rebellion was long gone (finished in 2009), and there had been no further serious attacks by AQIM since the audacious hostage taking of two young French men in Niamey in January (both were killed).

But in a blink of the eye Agadez has descended into chaos, with the arrival on Sunday night of a convoy carrying Libya’s former Security chief Mansur Daw. This fact could have gone largely unnoticed by the world, if it hadn’t been for the comments of a French military source that a much larger convoy passed through Agadez on Monday night. Originally it was believed to be up to 250 vehicles – the number has been discredited, but it’s fairly certain that a major convoy did arrive. The source added that Gadaffi and his sons “˜may’ join it en route to Burkina Faso where there had been confused reports of asylum being offered. The resulting media circus is history.

Mansur Daw presented them with a dilemma – the arrival of such a high-profile Libyan could signal others were on their way, but he was also presumably a fairly desperate man and one they owed a debt of gratitude to. While Niamey is not as littered as N’Djamena or Bamako with tattered billboards of a smiling and waving Gadaffi, there are strong links between the Guide and President. Gadaffi has funded Issoufou’s political campaigns, and as with other Sahelian neighbours, Libya built roads, hotels and donated agricultural equipment. Tuaregs respect him for decades of support for their independence struggles. Many ordinary Nigeriens feel that Gadaffi has been their champion. There was clearly an obligation to help.

Reflecting on the FM’s comments that “We have no means to close the border… It is too big and we have very, very small means for that” shows the complexity of the problems facing them. If Gadaffi really was coming, should they let him pass on his way to Burkina Faso? Was he even going there? Should they turn a blind eye and let him disappear into the desert, or should they arrest him and hand him over to the ICC? Would they even be able to find him?

Their initial confused position did not help. On one hand they had recognised the TNC, on the other they said they hadn’t yet decided what to do if and when Gadaffi turned up. Suddenly thrown into the media glare, it was almost a whole day before journalists could get an official reaction – a delay which seemed to add fuel to the flames of rumour.

Crucial to their decision must have been the worry that Niger’s hard-earned reputation for achieving peace and democracy, which was just beginning to allow them to return to the international fold, was about to be destroyed. EU sanctions against Niger were dropped after Issoufou’s election, and USAID had just come back. Now the World’s Most Wanted Man could be arriving on their doorstep – what would happen if they reneged on their responsibilities to the ICC?

In the event it was a false alarm. Given the mass of attention now focused on Niger, Gadaffi may do well to look for a different exit route (the vast wastelands of Tibesti/Ennedi in Chad may look like an attractive retirement option). But the fact remains that the border is still a very dangerous place, and the Nigerien government’s inability to secure it has been laid bare. Niger has bought some time to come up with a coherent strategy; but not much.

Celeste Hicks is a freelance journalist with a focus on African issues. She has a particular interest in the Sahel.