Sudan’s foreign debt: A Greek Tragedy is Sudan’s Woe – By Ahmed Badawi

Presidents Omar el-Bashir and Salva Kiir - the populations of both Sudan and South Sudan would benefit from debt cancellation

John Travolta would feel at home in a corner of Washington D.C. right now: Greece is the word dominating discussions in the corridors of H Street following the end of the IMF/World Bank annual meetings there.

Yet, with the shin-dig having been transformed from a global economic scoping forum into a mini G-7 summit (2.0), another case for emergency financial help – more pressing and compelling even than that of Greece – risks getting elbowed out of the world’s gaze: relieving Sudan quickly of its crushing US$38 billion foreign debt to help fulfill its huge potential. Indeed, despite improved economic performance over the last decade-and-a-half, poverty is still widespread (and acute in many areas) within Sudan, and the state of human development remains poor – especially in areas that have been wracked by conflict.

Don’t turn the page: Sudan’s President, Omar Al-Bashir, maybe many things to many people, but Sudan is not just another African country whose current government borrowed abroad recklessly and wasted and/or pocketed most of the funds for itself. Look beyond the headline figure. Around 80 per cent (US$30 billion) of Sudan’s external debt is “˜odious’, incurred, or representing interest repayment arrears, on loans in the era of the late President Jaffar Nimieiri. He was removed from office over 25 years ago – long before the fashioning of the “˜Washington consensus’ on free market reforms in developing countries, and long after John Travolta had binned the Brylcreem and dubious dance moves.

Indeed, Sudan’s final dime from the IMF came way back in 1985, while the World Bank’s last credit dried up nearly two decades ago; ditto loans from the European Union, the USA, and Canada due, initially, over Islamist extremism concerns and, thereafter, human rights issues during the north-south civil war and Darfur conflict. Not surprisingly, ordinary Sudanese people have been whacked hard by the delay of foreign debt relief, promised first by the international community following the signing of the 2005 peace agreement to end the north-south civil war and, thereafter, delayed consistently.

The lack of an even barely adequate social safety net for vulnerable social groups – the raison d’íªtre of foreign debt relief – has left most ordinary Sudanese wide open in facing domestic and external economic shocks to their living standards. The shocks have included, most recently, skyrocketing world food prices, the biggest and most prolonged slump in global demand since the Great Depression and, domestically, drastically scaled-back subsidies on bread and petrol, and a slide in real wages as imported inflationary pressures have surged since the independence of South Sudan in July.

Need an extra impetus for striking off Sudan’s Nimieiri-era debt quickly? Then how about doing it just to help the poorest of the world’s poor – South Sudanese who, for example, see one in ten children die before the age of one year – climb off the bottom? The fledgling Republic of South Sudan (RoSS) has agreed, albeit informally at present, to take on half of the arrears if they don’t get cancelled within two years. South Sudan also needs headroom in its balance sheet to take on new concessional foreign loans aggressively and fund massive public investments in health, education, agriculture, transportation, and infrastructure (as does Sudan, too).

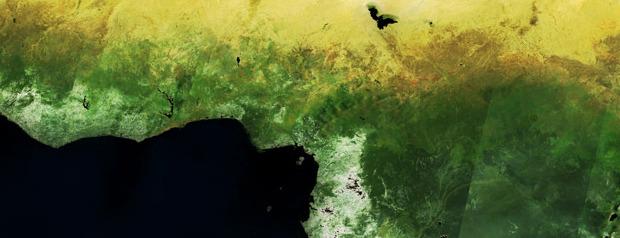

Rapid and generous foreign debt relief and, concurrently, access to new long-term “˜soft’ loans to underwrite “˜big-ticket’ public infrastructure projects for the “˜two Sudans’, also offers the international community a low-hanging fruit, right under its nose, to achieve its overarching goal: a stable Sudan and RoSS co-existing peacefully and prosperously. Most states in Sudan, and all of their counterparts in South Sudan, chug along as isolated, barren de facto landlocked countries, with all of the attendant huge challenges for development, stability, and mollifying feelings of estrangement from the central government that this generates within, and between, the “˜two Sudans’; ongoing fighting in Sudan’s southern border states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile gives two cases in point.

Freed from an unsustainable foreign debt, the nimble local private sector in Sudan would also quickly consolidate its role as the main engine of wealth and job opportunities; so the USA and other key international stakeholders would get more fiscal space to concentrate resources and attention (as they must) on standing-up RoSS and keeping it on its feet.

Even so, the United States government and European Union have both cautioned that conventional procedural requirements mean that Sudan will have to wait another two years, at least, to get comprehensive foreign debt relief. The two Sudans’s exceptional circumstances, however, call surely for exceptional measures by its bilateral creditors; the blinding speed at which the huge rescue packages for Ireland, Greece, and Portugal have been put together underlines that when the international community has the necessary political will to go like Grease Lightning, there’s indeed a way.

So, yes, a debt write-off for Sudan can – and must – be turbo charged.

Sudan (and, by default, South Sudan) already holds an unenviable world record for financial isolation from IMF, World Bank, the European Investment Bank and other standard sources of concessional project loans and balance of payments support – doubly vital for Sudan amid the slowing world economy and loss of oil fields to its southern neighbour. Nearly seven years on from the agreement that ended Africa’s longest-running civil war, both ordinary Sudanese and South Sudanese surely deserve delivery of the long-heralded peace dividend from the international community. If not now, as South Sudan has recently been birthed, then when? Or perhaps never.

Sudan’s foreign debt arrears are also so ancient and relatively small that they have long been provisioned for by its creditors. Put starkly, Sudan’s debt arrears could get cancelled in a couple of hours with no sweat – if the international community wished it so; placing undue emphasis on navigating procedural conditionality first just obfuscates this fundamental truth.

Detractors of speedy and comprehensive debt relief also point to the status of the “˜two Sudans’ as oil producers, collectively some 500,000 barrels per day. But many other resource-rich developing countries have needed comprehensive foreign debt forgiveness, too, in the past – Brazil, Zambia, Liberia, Bolivia, and Indonesia to name a handful – to kick-start higher and more inclusive economic growth rates and wider social safety nets.

Sudan, moreover, has used oil revenues to make good faith repayments – some US$1 billion to the IMF alone – to make a dent on its foreign debt arrears for well over a decade. Both Sudan (North) and the South also have a huge backlog of urgent economic development needs that can’t be met by oil revenue alone.

Suffice to add that both ordinary Sudanese and South Sudanese have not smelt a whiff of the IMF’s US$17 billion-plus increase in lending to crisis-affected and vulnerable African countries over the last two years; a double ignominy for them as they have already effectively subsidised IMF crisis-related loans to their much richer counterparts in Greece, Iceland, and Portugal to name a few.

It’s hard to imagine a more perverse transfer of wealth.

Exceptionally fast external debt forgiveness would buttress security across a huge swathe of the continent, too. Sudan and South Sudan together share borders with nine countries that house a third of Africa’s population. Extreme poverty-induced instability within or between the “˜two Sudans’ spills invariably over to their neighbours.

The Greek tragedy need not be Sudan’s – nor Africa’s – nightmare in disguise.

Let the international community subject Sudan’s foreign debt overhang swiftly to the one hairstyle that John Travolta hasn’t sported yet: a buzz-cut.

The author has written and advised extensively on country and reputational risk on Sudan at The Economist Intelligence Unit, Dun & Bradstreet, Fitchratings, Kroll, and WeberShandwick GJW, Public Affairs. He is also the former Middle East and Africa spokesperson for the International Finance Corporation (IFC), Washington D.C. He was the speechwriter for the Government of Sudan during the north-south Sudan peace talks Currently, Ahmed Badawi provides strategic counsel to the Government of Sudan and acts as Chief Consultant to The Global Relations Centre, based in Khartoum.

Hi Ahmed,

I’m not sure where you are based, but here in Khartoum everyone noticed the sudden spike (manipulation?) of the real USD/SDG exchange rate during the recent visit by President Armadinajad. While I do understand and respect a country / government’s right to self-determination and free trade, obligation to maintain law and order etc, please convince me that in the event of substantial debt relief, the resulting cash would not just be spent on Iranian guns.

However the situation came about, the fact is that this is $30bn of Other Peoples’ Money and I think it is reasonable that they should have some say in how it is used, as they undoubtedly did case-by-case in those countries that have received debt relief.