Biafra Revisited: civil war leader Ojukwu dies – By Richard Dowden

There was one astounding moment at Chinua Achebe’s Colloquium at Brown University in the US last year when three of the most influential men in the Biafran War came together on the platform – Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, the Oxford educated Biafran rebel leader, Professor Achebe himself, the most articulate proponent of the Biafran cause, and Wole Soyinka who flew into Biafra to act as a peacemaker and as a result was thrown into jail by the Nigerian President, General Yakubu Gowon. Only Gowon was missing.

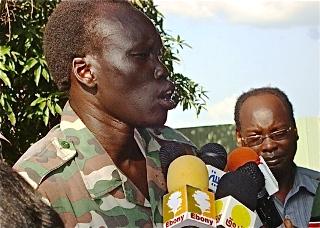

Just to see the three old men together was extraordinary – the slow-spoken, reflective Achebe in his beret, Soyinka with his shock of snowy hair and white beard speaking bluntly then enigmatically, and Ojukwu, a giant of a man in a huge black coat but now blind, led around by an assistant. He said very little but I wanted to ask a simple question, so when the session ended I managed to stop him for a moment and ask if he had any regrets about the war. He paused but did not turn his head. “History does not repeat itself,” he growled. “But if it did, I would do exactly the same again. Excuse me.” He moved on.

He died in London last Saturday and his death may trigger a re-assessment of that terrible war. In so many ways the Biafran conflict defined war in Africa for the rest of the century. It challenged the universal agreement among the newly independent African states to accept the colonial borders. The Ibos attempted to leave Nigeria and create their own state, (although they would have taken with them several other ethnic groups, like the Ibibios, the Annanga and the Ogojas, who were not consulted). This tribally based rebellion was to be replicated throughout the continent in following years. The war divided Africa, with Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire and Tanzania supporting the Biafran cause and other countries backing Nigeria. A divided African Union prevented it acting as a peacemaker, and from then on the AU played almost no role in ending wars in Africa.

Biafra was also about resources – oil in this case, which supercharged the conflict and ensured that outsiders like Britain took sides and supplied weapons. While not causing Africa’s subsequent wars, oil, diamonds, coltan and other valuable resources have exacerbated and prolonged conflicts. It did not however divide the world along Cold War lines. The Soviet Union also supplied weapons while the US took a neutral stance imposing its own arms embargo on both sides.

But perhaps Biafra’s greatest impact was its image. The last time the world had seen masses of starving people was at the end of the Second World War. The “˜Biafran baby’ – a starving child with huge sad eyes, stick-like limbs and bloated stomach – became a defining image of Africa for the next half century as wars broke out in almost half the continent’s states.

Aid agencies, which had had few emergencies since the end of World War II, found a new role in Biafra and there confronted all the problems they were to face elsewhere in Africa in the coming decades. A whole generation of aid workers were forged in the Biafran fire. The biggest problem for the aid agencies was that they knew some of the food and medical supplies were being taken by the combatants, thereby prolonging the war. The aid air bridge was also used by arms suppliers and one aid plane was shot down by the Nigerians. The Nigerian government tried to starve out the rebels. Chief Awolowo, then a minister, said in 1968 “all is fair in war and starvation is one of the weapons of war. I don’t see why we should feed our enemies fat in order for them to fight us harder.”

On January 12th 1970 the war ended with the collapse of Biafra and the flight of Ojukwu (although he said he would die rather than run away). General Yakubu Gowon declared that there would be no victors and no vanquished and there appears to have been no retribution once the fighting stopped. But there was no peace building or reconciliation either. Nigeria returned to peace, Ojukwu returned to Nigeria and was given an official pardon. But many Ibos feel they have been excluded from high office ever since and there has been little discussion of the war or its effects. The history of the war and its causes is not taught in schools and until Chimamanda Adichie’s novel Half of a Yellow Sun there was no written memory of what happened.

Perhaps with the death of Ojukwu that will change.

Richard Dowden is Director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa: altered states, ordinary miracles

Richard, thanks for your tribute. While it is indeed a tragedy that the story of the war is not explored in educational settings in Nigeria, I differ with your last statement though “until Chimamanda Adichie’s novel Half of a Yellow Sun there was no written memory of what happened”. There are indeed several memoirs of the war – both memoir, fiction, biographies, autobiographies etc. I grew up devouring them…in an attempt to understand. I still do not.

Dear Mr Dowden,

Thank you for a good article on Biafra, and Ojukwu. While i have read your book “Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles”, and felt you were quite objective in the writing, i must say here that the last part of this piece, where you state that there’s no written memory of the war is shocking in its simplistic and academic laziness.

It is easy to assume this but having grown up in NIgeria myself, and would have loved to see Ojukwu’s and Gowon’s memoirs on the war, books abound, before Adichie, as this site below shows

http://www.kwenu.com/igbo/igbowebpages/Igbo.dir/Biafra/books_on_biafra.htm

Thank you for your interest, and for keeping the conversation going.

C. Adepoju

Books on Biafra

Compiled by

Dan Obi Awduche

University of Massachussettes, Amherst, MA.

AUTHOR Ojukwu, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu

TITLE Because I am involved

PUBLISHER Ibadan : Spectrum Books Ltd., 1989

AUTHOR Ojukwu, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu,

TITLE Principles of the Biafran revolution : as enunciated by General C. Odumegwu Ojukwu.

PUBLISHER Cambridge, Mass. : Biafra Review, 1969

AUTHOR Ojukwu, Emeka Odumegwu

TITLE Biafra; selected speeches and random thoughts of C. Odumegwu Ojukwu, with diaries of events.

PUBLISHER New York, Harper & Row

AUTHOR Madiebo, Alexander A.

TITLE The Nigerian revolution and the Biafran war

PUBLISHER Enugu, Nigeria : Fourth Dimension Publishers, 1980

[Note: Madiebo was the general officer commanding the Biafran army]

AUTHOR Nwankwo, Arthur Agwuncha and S. Udochukwu Ifejika,

TITLE The making of a nation: Biafra

PUBLISHER London, C. Hurst, 1969.

AUTHOR Nwankwo, Arthur Agwuncha

TITLE Nigeria: the challenge of Biafra

PUBLISHER London, R. Collings, 1972.

AUTHOR Forsyth, Frederick,

TITLE The Making of a Nation: The Biafran story.

PUBLISHER Baltimore, Penguin Books [1969]

AUTHOR: Forsyth, Frederick, 1938-

TITLE: Emeka

Edition: Reprinted with corrections 1992

PUBLISHER: Ibadan, Nigeria : Spectrum Books ; Jersey, Channel Islands, UK : Safari Books (Export), 1992.

AUTHOR Azikiwe, Nnamdi

TITLE Origins of the Nigerian Civil War

PUBLISHER Apapa : Nigerian National Press, 1969

AUTHOR Opia, Eric Agume

TITLE Why Biafra? : Aburi, prelude to Biafran tragedy

PUBLISHER San Rafael, Calif. : Leswing Press, c1972.

AUTHOR Chima, Alex.

TITLE Future lies in a progressive Biafra: a socio-economic history of the republic of Biafra.

PUBLISHER London, Alex Chima, 1968.

AUTHOR Odogwu, Bernard, 1936-

TITLE No place to hide : crises and conflicts inside Biafra

PUBLISHER Enugu, Nigeria : Fourth Dimension, 1985.

[Note: Odogwu was head of Biafra’s secret service unit]

AUTHOR Achuzia, Joe O. G.

TITLE Requiem Biafra / by Joe O.G. Achuzia.

PUBLISHER Enugu, Nigeria : Fourth Dimension Publishers, 1986.

[Note: Achuzia was one of the more renowned Biafran field commanders]

AUTHOR Ademoyega, Adewale

TITLE Why we struck : the story of the first Nigerian coup

PUBLISHER Ibadan (Nigeria) : Evans, 1981

[Note: Ademoyega was one of the five majors that intiated Nigeria’s first military coup]

AUTHOR Gbulie, Ben.

TITLE Nigeria’s five majors : coup d’etat of 15th January 1966, first inside account.

PUBLISHER Onitsha, Nigeria : Africana Educational Publishers (Nig), c1981

AUTHOR Mainasara, A. M

TITLE The five majors : why they struck

PUBLISHER Zaria [Nigeria] : Hudahuda Publishing Co., 1982.

AUTHOR Nwigwe, Henry Emezuem.

TITLE Nigeria – the fall of the First Republic

PUBLISHER London, Motorchild Press, [1972]

AUTHOR Azikiwe, Nnamdi

TITLE Peace proposals for ending the Nigerian civil war.

PUBLISHER London : Colusco, 1969

AUTHOR Gbulie, Ben.

TITLE The fall of Biafra

PUBLISHER Enugu, Anambra State, Nigeria : Benlie, 1989

AUTHOR Wiseberg, Laurie Sheila

TITLE The international politics of relief : a case study of the relief operations mounted during the Nigerian civil war (1967-1970)

PUBLISHER Thesis – University of California, Los Angeles, 1973.

AUTHOR Lloyd, Hugh G et al TITLE The Nordchurchaid airlift to Biafra, 1968-1970. An operations eport. PUBLISHER Copenhagen, 1150 Kobenhavn K., Folkekirkens Nodhjalp, Eksp.: Kobmagergade 26, 1972

AUTHOR East-Central State (Nigeria). Ministry of Works, Housing, and Transport

TITLE Report on war damages to roads, bridges, waterworks and equipment in the East Central State of Nigeria.

PUBLISHER Enugu, Printed by the Govt. Printer 1970

AUTHOR Ozalla, M. Odogwu.

TITLE Ojukwu’s new type democracy

PUBLISHER Lagos (Committee of Ibo Intellectuals) 1969

AUTHOR Ozalla, M. Odogwu.

TITLE Ojukwu’s “self-determination”; a reappraisal in the light of international politics

PUBLISHER (Apapa 0, Printed by the Nigerian National Press 1969.

AUTHOR United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on Africa.

TITLE Report of the Special Coordinator for Nigerian Relief. Hearing, Ninety-first Congress, first session. April 24, 1969.

PUBLISHER Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1969

AUTHOR Asika, Ukpabi.

TITLE No victors, no vanquished.

PUBLISHER (Enugu) East-Central State Information Service 1968

AUTHOR Graham-Douglas, Nabo B.

TITLE Ojukwu’s rebellion and world opinion

PUBLISHER London : Galitzine, Chant, Russell and Partners, 1968

AUTHOR Eastern Nigeria. Ministry of Information.

TITLE Nigerian crisis 1966: (Eastern Nigeria viewpoint)

PUBLISHER Enugu, Eastern Nigeria. Ministry of Information. 1966.

AUTHOR Ugobelu, Egbebelu.

TITLE Biafra war revisited : a concise account of events that led to the Nigerian civil war

PUBLISHER Atlanta, GA : ProPrints of Atlanta, 1992

AUTHOR Enonchong, Charles.

TITLE I know who killed Major Nzeogwu! : an investigation into the most secret cover-up of the Nigerian Civil War

PUBLISHER Lagos : Century, 1991

AUTHOR Idahosa, Patrick E.

TITLE Truth and tragedy : (a fighting man’s memoir of the Nigerian Civil War)

PUBLISHER Ibadan : Heinemann Educational Books, 1989

AUTHOR Obikeze, Dan S. and Ada A. Mere.

TITLE Children and the Nigerian Civil War : a study of the rehabilitation programme for war-displaced children

PUBLISHER Nsukka : University of Nigeria Press, 1985.

AUTHOR S.C. Nwoye & E. Ikegbune.

TITLE Biafrana at Nsukka : a list of materials on the Nigerian Civil War available at the Nnamdi Azikiwe Library (University of Nigeria, Nsukka).

PUBLISHER Nsukka : University of Nigeria Library,1983

AUTHOR O’Malley, Patrick.

TITLE “No such country” : footnotes on the Nigerian civil war

PUBLISHER (Zomba) : University of Malawi, History Dept.,1984

AUTHOR Ngoh, Victor Julius

TITLE The United States and the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970 : an analysis of the American policy toward the war

PUBLISHER Thesis (Ph. D..) — University of Washington, 1982.

AUTHOR Uwanaka, Charles U

TITLE Nigerian civil war : causes, events (1956-1967)

PUBLISHER Ebute-Metta : De Mediator Press, 1981.

AUTHOR Ekwensi, Cyprian

TITLE Divided we stand : a novel of the Nigerian Civil War

PUBLISHER Enugu, Nigeria : Fourth Dimension, 1980.

AUTHOR Akinyemi, A. B.

TITLE The British press and the Nigerian civil war : the godfather complex (NIIA monograph series. no. 2)

PUBLISHER Oxford University Press, 1979

AUTHOR Uku, Skyne R

TITLE The Pan-African movement and the Nigerian civil war

PUBLISHER New York : Vantage, 1978

AUTHOR Urhobo, Emmanuel.

TITLE Relief operations in the Nigerian civil war

PUBLISHER Ibadan, Nigeria : Daystar Press, 1978

AUTHOR Cohen, Robin.

TITLE “A greater south”: or what might have happened in the Nigerian Civil War.

PUBLISHER University of Birmingham, Faculty of Commerce and Social Science, Series C, no. 22. 1971

AUTHOR Uwechue, Raph.

TITLE Reflections on the Nigerian civil war; facing the future. With forewords by Nnamdi Azikiwe & Leopold Sedar Senghor.

PUBLISHER New York, Africana Pub. Corp. 1971

AUTHOR Panter-Brick, S. K. ed.

TITLE Nigerian politics and military rule: prelude to the Civil War

PUBLISHER University of London; 1970

AUTHOR Obasanjo, Olusegun.

TITLE My command : an account of the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970

PUBLISHER Ibadan, : Heinemann, 1980.

[Note: Obasanjo was one of Nigeria’s field commanders during the war. He became head of state after the assasination Muritala Mohammed in the late ’70s]

AUTHOR Obasanjo, Olusegun.

TITLE Not my will

PUBLISHER Ibadan : University Press Ltd., 1990

AUTHOR Obasanjo, Olusegun.

TITLE Nzeogwu : an intimate portrait of Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu

PUBLISHER Ibadan : Spectrum Books, 1987

AUTHOR Aguolu, Christian Chukwunedu

TITLE Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970; an annotated bibliography.

PUBLISHER Boston, G. K. Hall, 1973.

AUTHOR Affia, George B.

TITLE Nigerian crisis, 1966-1970: a preliminary bibliography

PUBLISHER University of Lagos, Yakubu Gowon Library

AUTHOR Cervenka, Zdenek

TITLE The Nigerian war, 1967-1970. History of the war; selected bibliography and documents.

PUBLISHER Frankfurt am Main, Bernard & Graefe, 1971.

AUTHOR Amadi, Elechi, 1934-

TITLE Sunset in Biafra: a civil war diary.

PUBLISHER London, Heinemann Educational, 1973.

AUTHOR Akpan, Ntieyong Udo.

TITLE The struggle for secession, 1966-1970; a personal account of the Nigerian Civil War

PUBLISHER London, F. Cass

AUTHOR Achebe, Chinua.

TITLE Christmas in Biafra and other poems.

EDITION [1st ed.]

PUBLISHER Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, 1973.

AUTHOR Emecheta, Buchi.

TITLE Destination Biafra : a novel

PUBLISHER London ; New York : Allison & Busby ; New York, N.Y. : Distributed by Schocken Books, 1982

AUTHOR Ike, Vincent Chukwuemeka, 1931-

TITLE Sunset at dawn : a novel about Biafra

PUBLISHER London : Collins and Harvill Press, 1976.

AUTHOR Frederick L. Shiels (Editor)

TITLE Ethnic separatism and world politics

PUBLISHER Lanham, MD : University Press of America, c1984.

AUTHOR Schabowska, Henryka.

TITLE Africa reports on the Nigerian Crisis : news, attitudes and background information : a study of press performance, government attitude to Biafra and ethnopolitical integration

PUBLISHER Uppsala : Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, 1978.

AUTHOR Parise, Goffredo.

TITLE Biafra.

PUBLISHER Milano, Libreria Feltrinelli, 1968.

AUTHOR Waugh, Auberon.

TITLE Biafra: Britain’s shame

PUBLISHER London, Joseph, 1969.

AUTHOR Mok, Michael.

TITLE Biafra journal.

PUBLISHER New York, Time-Life Books [1969]

AUTHOR Sullivan, John R.

TITLE Breadless Biafra

PUBLISHER Dayton, Ohio, Pflaum Press, 1969.

AUTHOR Oluleye, James J.

TITLE Military leadership in Nigeria, 1966-1979

PUBLISHER Ibadan : University Press Ltd., 1985.

AUTHOR Ekwe-Ekwe, Herbert

TITLE The Biafra war : Nigeria and the aftermath

PUBLISHER Lewiston, N.Y., USA : E. Mellen Press, c1990.

AUTHOR De St. Jorre, John

TITLE The brothers’ war; Biafra and Nigeria

PUBLISHER Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1972.

AUTHOR Nafziger, E. Wayne.

TITLE The economics of political instability : the Nigerian-Biafran war

PUBLISHER Boulder, Colo. : Westview Press, 1983.

AUTHOR Stremlau, John J.

TITLE The international politics of the Nigerian civil war, 1967-70

PUBLISHER Princeton University Press, c1977.

AUTHOR Joseph Okpaku, editor.

TITLE Nigeria: dilemma of nationhood; an African analysis of the Biafran conflict.

PUBLISHER New York, Third Press

AUTHOR Collis, William Robert Fitz-Gerald

TITLE Nigeria in conflict

PUBLISHER London, Secker & Warburg, 1970.

AUTHOR Nwankwo, Arthur Agwuncha

TITLE Nigeria: the challenge of Biafra

PUBLISHER London, R. Collings, 1972.

AUTHOR Wiseberg, Laurie S.

TITLE The Nigerian civil war, 1967-1970; a case study in the efficacy of international law as a regulator of intrastate violence

PUBLISHER Southern California Arms Control and Foreign Policy Seminar, 1972>

AUTHOR Cervenka, Zdenek

TITLE The Nigerian war, 1967-1970. History of the war; selected bibliography and documents.

PUBLISHER Frankfurt am Main, Bernard & Graefe, 1971.

AUTHOR Saro-Wiwa, Ken

TITLE On a darkling plain : an account of the Nigerian civil war

PUBLISHER London : Saros, 1989.

AUTHOR Balogun, Ola

TITLE The tragic years : Nigeria in crisis, 1966-1970 PUBLISHER Benin City, Nigeria : Ethiope Pub. Corp., 1973.

AUTHOR Niven, Rex, Sir

TITLE The war of Nigerian unity, 1967-1970

PUBLISHER Totowa, N.J., Rowman and Littlefield

AUTHOR Ogbemudia, S. O.

TITLE Years of challenge PUBLISHER Ibadan : Heinemann Educational Books, 1991.

AUTHOR Thompson, Joseph E.

TITLE American policy and African famine : the Nigeria-Biafra War, 1966-1970

PUBLISHER New York : Greenwood Press, 1990.

AUTHOR Ogbudinkpa, Nwabeze Reuben

. TITLE The economics of the Nigerian Civil War and its prospects for national developmment

PUBLISHER Enugu, Nigeria : Fourth Dimension Publishers, 1985.

AUTHOR Mezu, Sebastian Okechukwu

. TITLE Behind the rising sun

PUBLISHER London, Heinemann, 1971.

AUTHOR Nwapa, Flora

TITLE Never again

PUBLISHER Trenton, N.J. : Africa World Press, 1992.

AUTHOR Iroh, Eddie.

TITLE The siren in the night

PUBLISHER London : Heinemann, 1982.

AUTHOR Iroh, Eddie.

TITLE Toads of war

PUBLISHER London : Heinemann, 1979.

AUTHOR Nweke, G. Aforka.

TITLE External intervention in African conflicts : French-speaking West Africa in the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-70

PUBLISHER African Studies Center, Boston University, 1976.

AUTHOR Cronje, Suzanne

TITLE The world and Nigeria: the diplomatic history of the Biafran War, 1967-1970.

PUBLISHER

AUTHOR McLuckie, Craig W.

TITLE Nigerian Civil War literature : seeking an “imagined community”

PUBLISHER Lewiston, NY : E. Mellen Press, c1990.

AUTHOR Kirk-Greene, A. H. M. (Anthony Hamilton Millard)

TITLE Crisis and conflict in Nigeria: a documentary sourcebook

PUBLISHER London, Oxford University Press, 1971.

AUTHOR Awolowo, Obafemi

TITLE Awo on the Nigerian Civil War

PUBLISHER Ikeja, Nigeria : J. West Publications, 1982

The real story of Biafra is yet to be told. The truth is what will set the nation Nigeria free.

My statement that there was no written history of the Biafra war is wrong. I was thinking of all those military sections in UK bookshops that cover every war from ancient Greece to Afghanistan but never anything about Biafra. Maybe they only do wars involving Europeans or Americans so i was taking a Euro centric view. Chuwudi Adepoja points to Dan Obi Awduche’s list of 86 books – the vast majority of them by Nigerians published in Nigeria. SOAS library has 59.

Thank you for clarifying.

Regards,

Chukwudi.

Dear Chukwudi Adepoju

Thank you for this welcome and comprehensive reading list

Regards

Elizabeth

[…] AFRICAN FAMINE: CROWN PRINCE & PRINCESS of DENMARK and DUKE & DUCHESS of UK (MaximsNewsWORLD)AGU days 2 and 3: some notable talksRevisiting Biafra: civil war leader Ojukwu dies – By Richard Dowden […]

Thank you for your piece on Biafran war. However, the Biafran war was never a “tribally based rebellion…”as you wrote. It was a war based on self defence of then the people of Eastern Nigeria who were being killed enmasse in Northern Nigeria.There was a pogrom and the Ibos were victims. The people of Eastern Nigeria did not plan to leave Nigeria but the mass killings of their folk in the north and inaction of the Nigerian government necessitated the demand for the Biafra.Ibos were not the only Biafrans. The Efiks, Ibibio and Ogoja youths fought vilantly for Biafra.

Technologically and politically,Africa would have been a diifferent continent today if the issues of injustice and unfair play against the Biafrans were well treated.

Finally, Biafra is not only about the starving children; it is also about people’ right for self determination.Biafra is also about an African people who faced with necessity achieved great technologies within a short period of time.

a very good website and an even more impressive bibliography. We may or may not see Ojukwu’s memoirs but the Nigerians are welcome to study the history of the war through the several books of other authors.

We need history to signpost the future!

Thank you for that. Are there any videos of that event in 2010?