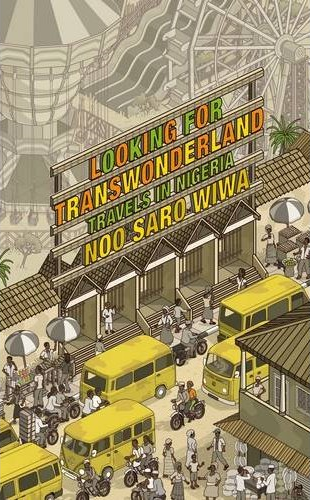

Noo Saro Wiwa goes home: Looking for Transwonderland – A review by Magnus Taylor

Noo Saro Wiwa’s heritage made writing a book about Nigeria a complicated proposition. As the daughter of murdered environmental activist Ken Saro Wiwa, one can imagine how Noo fought the idea of piggybacking on her long deceased father’s fame when, as a fine and dryly observant writer, she would have believed that success could be achieved without such paternal association.

Noo Saro Wiwa’s heritage made writing a book about Nigeria a complicated proposition. As the daughter of murdered environmental activist Ken Saro Wiwa, one can imagine how Noo fought the idea of piggybacking on her long deceased father’s fame when, as a fine and dryly observant writer, she would have believed that success could be achieved without such paternal association.

Noo admits that “˜I feel like I’m carrying my father’s name…it’s not just me by myself’ – her words are, in a sense amplified by association, and it is perhaps partly this influence that motivated her to construct a careful and largely non-judgemental account of her homeland. In conversation she is a little more forthright in her opinions about modern Nigeria, expressing exasperation and confusion at the current state of the country. This, she says, “˜affects you on a deep level…[as] it represents who you are.’ And, I sense this is accentuated by being a long-time diaspora Nigerian, inescapably connected to what is perceived by the rest of the world as a failing state.

Another complication is the position she holds as Nigerian by birth but very much English by upbringing. As a child Noo was however taken for uncomfortable annual summer trips back to Nigeria. She tells us that whilst there she always “˜wanted to go back to the place I called home: leafy Surrey, a bountiful paradise of Twix bars and TV cartoons and leylandii trees.’ This attitude is accentuated by the execution of Ken in 1995 at the hands of the thuggish Abacha regime. From this point on, “˜Nigeria sapped my self-esteem; it was the hostile epicentre of a life in which we languished at the margins in England…I wanted nothing to do with the country.’ The pain of losing her father is clearly evident in Saro Wiwa’s writing, and whilst the passage of 15 years has made it possible for her to speak and write with an air of detachment from that horrific event, it is also clear that this book was never just going to be about travel.

Saro Wiwa admits that writing the book was an unexpectedly cathartic process. From setting out to compose a reasonably detached account of her journey, she is noticeably sucked in to her own personal narrative, jolted by the regular recognition of her family name and emotionally affected by the return to the family home in the Delta city of Port Harcourt. She poignantly describes how several years ago the family re-assembled the bones of Ken’s body, unceremoniously returned to them by the newly-installed civilian government in a large bag.

Compelling personal narrative aside, Saro Wiwa, with her history of guide-book journalism (she has written for both Rough Guide and Lonely Planet), is a competent and convincing travel writer with an eye for the absurd. Not many people backpack around Nigeria, but she demonstrates that it is possible to negotiate what is often an intimidating place largely on local transport and with a day-by-day budget that doesn’t allow constant splurges on luxury hotels. Whilst Saro Wiwa does take in some interesting sites – rickety local museums, Benin bronzes and the wonderful bird-filled Chad Basin National Park (steadily encroached upon by the Southward drift of the Sahara desert) – she seems more interested in teasing out the humour of, for example, the University of Ibadan’s somewhat anarchic dog show (“˜I beg, don’t run, o!’ the MC implored down the mike. “˜The dog will pursue you if you run.’) Or in dead-pan style pretending (by phone) to be a prospective middle-aged “˜sugar mummy’ replying to newspaper adverts such as the following:

“˜Julius, 28, needs a rich, sexy single sugar mummy, aged between 30-45 for financial support in exchange for the fun of her life.’

That is one of the refreshing things about Saro Wiwa’s book. It lacks the po-faced concern of most academic, journalistic or literary accounts of poor old benighted Africa, and concentrates more on the humour of the place. She tells me that despite the depressing poverty and neglect she found in Nigeria “˜it’s impossible not to laugh there.’

“˜When you’re raised in two different cultures, you don’t buy into the myths of either’ says Noo. This desire to avoid “˜myths’ about Nigeria – composed from international stereotypes and childhood experience – is a constant throughout the book. One senses that Saro Wiwa was personally surprised by how much she enjoyed rediscovering the country of her birth. Towards the end of the book she comments that “˜my dislike for the country was softening into a wavering ambiguity’ – a characteristically undemonstrative assertion.

Saro Wiwa doesn’t let us romantically fall for an idealised version of Nigeria. Even if such a thing existed, it was (by her own admission) too expensive to visit all the waterfalls and remote panoramas which always seem to require the traveller to hire a 4×4 (at great expense). In Nigeria money talks and good impressions can be bought. By slumming it a bit, talking to many ordinary Nigerians, and letting us into a little of the Saro Wiwa story, Noo has crafted a highly enjoyable and revealing account of her complicated homeland.

Magnus Taylor is Managing Editor, African Arguments Online.

Looking for Transwonderland will be launched at SOAS on 24th Jan – for more details click here

[…] a South Bank event in July last year, Noo Saro-Wiwa, the author of Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria, was asked by the host why she had chosen to deliver a piece of travel literature on Nigeria rather […]

cialis online cialis online