Whither Senegalese democracy? – By Carlos Oya

On 26th February Senegal will experience one of the most controversial and hotly contested presidential elections of its relatively long democratic history. Since the first presidential elections in 1978 only the 1988 contest was marred by such tension and violence. The forthcoming elections are certainly the most violent in recent history. Up to six people have been killed in different clashes and demonstrations since the Constitutional Council validated Wade’s candidacy on 26 January.

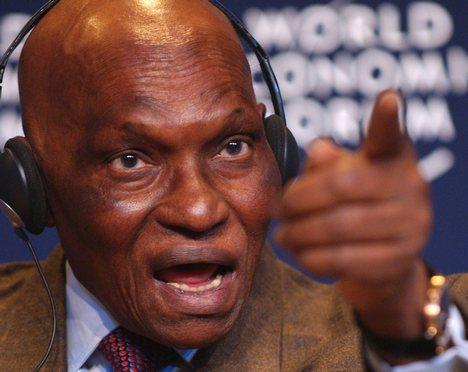

The Council accepted President Wade’s argument that his first term does not count towards the constitutionally stipulated two-term presidential limit because the amendment was introduced one year after he was first elected in 2000. A technicality of dubious validity has allowed Wade to run for his third term, despite his long-standing promise to limit a President’s mandate to two consecutive terms. In a recent visit, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo , who comes as an observer for the presidential elections this Sunday, has called Wade to withdraw from the presidential race, reminding him of the time when the Senegalese President persuaded Obasanjo not to run for a third time in Nigeria. However, domestic and international pressure has been insufficient to persuade Wade that his time is up. He has been defiant and his intransigence has further stirred existing tensions.

Following the controversial decision by the Constitutional Council, eight of the 13 presidential challengers signed an agreement to form a united front of anti-Wade politicians and civil society organisations under the banner of the M23 movement, with reference to violent June 23rd protests that forced the president to abandon a controversial constitutional referendum that would have eased his re-election in the first round of the forthcoming election. The anti-Wade opposition claims that Wade’s intention is to turn Senegal into a pseudo-monarchy by paving the way for his son Karim Wade to succeed him should he win this election. They also decry the authoritarian drive that the President has gradually taken since his last re-election in 2007 and his habit of manipulating Senegal’s democratic institutions to his own and his entourage’s benefit. In their view and that of many Senegalese people, Wade has undermined Senegalese democracy.

However, despite the joint campaign against Wade, one of the key opposition candidates, Macky Sall (former prime minister with Wade and one of the most popular figures contesting the election) finally decided to carry out his own campaign separate from the rest of the anti-Wade movement. This underscores one of the major weaknesses of the opposition – its inability to form a coalition under one single candidate who could capitalize on the growing discontent with Wade. In fact, the lack of unity is a result of the insistence of some established politicians (Ousmane Tanor Dieng, Moustapha Niasse, Idrissa Seck) in trying their own individual chances. Lack of consensus on a single opposition candidate may also be due to the absence of a political figure who can match Wade’s charisma and cunning.

The likely outcome on 26 February will be a fragmentation of the opposition vote and possibly a victory of Wade in the first round, albeit without sufficient majority. It will be in the second round when the opposition group will have no option but to rally behind the best placed candidate against Wade, which would enhance the opposition’s chances.Wade will of course, in such a scenario, try to co-opt some of the opposition candidates in order to weaken the appeal of his main rival in the second round. He has been able to manipulate different politicians in previous occasions, especially those coming from his own “˜political family’, PDS, like Macky Sall and Idrissa Seck. A firm promise of succession might lure these leaders to support Wade in order to secure a way into power before the mandate ends. So, a second round may not necessarily end Wade’s chance to win.

Both Wade and Macky Sall have been very active during the campaign and, while they have toured much of the Senegalese territory, they have been careful to focus on those areas where they have a chance to win votes, i.e. rural areas, small towns and religious constituencies. They have in particular targeted the powerful Mouride brotherhood, based in the town of Touba. Religious and other customary notables have been focused on by Wade’s campaign while demonstrations and anti-Wade mobilisations have been concentrated in Dakar and some other urban centres.

Meanwhile, most other opposition candidates essentially wasted one week of campaign by focusing their efforts on the demonstrations against Wade’s candidacy, which concentrated in Dakar and eventually waned. Therefore, their chances of winning much of the rural vote have been probably undermined by their tactics of trying to force Wade’s withdrawal before the election. After all, the rural-urban voting divide may well be the key to the presidential election results. Wade knows how unpopular he has become in urban areas, especially in Dakar, but this can be compensated for with enough support from rural areas and from large segments of the powerful religious constituencies, especially the Mourides.

The fact that the campaign has in the end taken place despite fears that mass-scale violence would prevent the organisation of the elections, suggest that Senegal’s democratic institutions are strong enough to survive this impasse. A different matter is what may happen if Wade wins the election. Unrest may significantly increase although mass-scale violence is less likely. Even the leaders of the rebel youth movement Y’en marre claim their stance is non-violent and believe Senegalese society is not ready for mass-scale violence. Perhaps Wade is also aware of this and hence his insistence in going ahead with a project that would otherwise look extremely risky.

Wade seems to believe that his legacy after twelve years in power justifies an extension of his mandate, not least to complete some of the flagship projects that he wants to be remembered for (the new airport, roads and better mobility in Dakar). But Wade’s record is actually far from impressive. He has certainly left some visible legacy in the form of new roads, a rehabilitated port and an ambitious airport project (as well as other controversial investments like the Renaissance monument). However, his main infrastructural projects have not yet been completed, despite so many announcements and much fundraising. The economy has grown at reasonably good rate (hovering around 5% per year) but somewhat erratically and certainly not as fast as many African economies enjoying the commodity boom that has lasted since the early 2000s. This is despite the improvement in some indicators of the investment climate and an increase in foreign investment.

More worrying is the lack of structural transformation in the economy, the sluggish performance of the industrial sector and the dubious record in agriculture. Therefore, apart from the few flagship infrastructural improvements, the economy is not significantly better twelve years after Wade took power. In some ways, public infrastructure has actually deteriorated to an alarming extent. Power outages have become a habit and seriously undermined prospects for economic activities, especially in industry and services, while making life difficult, especially for the average urban dweller. Protests against unreliable power supply and mismanagement have also become common currency in the past few years. The record in terms of poverty reduction and employment, as far as statistics can show, is also quite disappointing, and there is a sense, especially in urban areas, that despite some visible improvements in the quality of roads and a real estate boom, there has been deterioration in living standards. Increases in basic energy and food prices since 2007 have not helped either, making social discontent ever more evident, especially in the streets of Dakar.

Overall, Wade’s regime has not achieved a coherent sustainable economic strategy for the country and key structural vulnerabilities persist while opportunities for more durable economic transformation are missed out. The tragedy is that organised opposition and civil society organisations have concentrated largely on governance issues, but have not come up with an alternative credible development strategy for the country. Will the electorate keep faith in the “˜devil they know’? Or will the “˜enough is enough’ slogan (Y’en marre) prevail?

Carlos Oya is Senior Lecturer in the Political Economy of Development at SOAS, London.