Ghana’s 55 years of independence– poised for a great leap forward? – By Nana Ampofo at Songhai Advisory

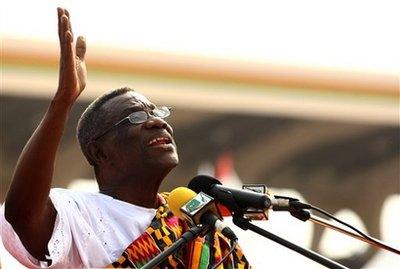

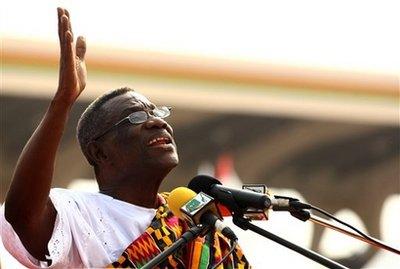

Ghana marked 55 years of independence from colonial rule on 6 March 2012 – “no mean achievement” in the life of any nation, according to President John Evans Atta Mills speaking at the national celebrations. He added that “certainly, we have not reached our final destination as regards our march towards growth and development but we have made significant gains and cannot afford to destroy what we have toiled to build”.

Over the past 2 decades, Ghana has established a record of political stability and socio-economic progress. However, the country is again experiencing something of a rite of passage. If in 1957 it was national self-determination, and in 1992 it was multiparty democracy, Ghana of the moment must come to terms with challenges and opportunities which include: significant hydrocarbon resources, income inequality and job creation, political polarisation, public accountability gaps, economic diversification, infrastructural development and macroeconomic stability.

An Historical Transformation

Changes in the former Gold Coast over the past 30 years, never mind the last 55, have been substantial. Around the time of independence, the total population was only 6.7 million and life expectancy averaged 46.8 years. By 1980, the population had climbed to 10 million and then hit 24.4 million in 2010 with average life expectancy of 65 years. This expansion implies greater strain on scarce national resources and the institutions that govern them; however notwithstanding a highly polarised political environment, Ghana’s last coup was in 1981 and the multiparty democracy instituted in 1992 remains in place.

A slow rolling economic transformation has taken place at the same time. In 1980, GDP per capita was US$600 in purchasing power parity terms but has now climbed to US$2,700 (according to the IMF.) Poverty levels have also fallen,[1] and in 2010 Ghana was re-classified from a least-developed to a lower middle income country. Over the same period, the share of agriculture, services and industry in the economy has shifted from 60%, 34% and 6.5% respectively to 30% for agriculture, 51% for services and 19% for industry.

On the Horizon

It is clear then that Ghana has made material gains over the past five and a half decades. But this is not to deny the frustration or disappointment of sections of the population. Although Ghana is a wealthier country it is also a more unequal one. The poorest 10% of the population accounted for 2.87% of national income in 1989 but 2.06% in 2006, according to the World Bank poverty statistics. Headline inflation is now in the single digits[2] but Ghanaians have not shaken off the trauma of over-20% per annum CPI in 2009. Moreover, energy price volatility, which is on-going, is felt most keenly by those at the bottom of the ladder. They are also typically the most exposed to shortcomings in the availability of public utilities – water, electricity and sewage particularly (recent load shedding has been felt across most sections of society).

A third problem, impacted by and impacting upon the above, is joblessness. Our own experience is that young Ghanaians across social strata complain of inadequate job opportunities. And yet, according to the most recent World Bank enterprise survey (2007) only 4.5% of respondent firms view an inadequately educated workforce as a major constraint to doing business (compared to 22.6% in Africa as a whole and 27.4% across the world). In contrast, 18% viewed infrastructure as a major constraint and 66% thought the same of access to finance.

All of which would seem to suggest that expanding access to education (a key discussion point in the upcoming polls), though important, is not a silver bullet for job creation. For financial services, single digit inflation for the longest uninterrupted period in decades is a salve, and lending rates are now falling. But Ghana must continue the esoteric business of economic transformation. Policy makers must create an environment for higher value added and more labour intensive economic activity – to which Ghana’s infrastructural deficit is an impediment. Ghana’s recently discovered oil wealth is a spur for GDP growth and government revenue, but it is not a job creator (certainly not directly).

A Great Leap?

Therein lies the rub. Government is a critical conduit for tackling the infrastructure gap. But naturally there are questions around capacity – picking the right projects and implementing them – but also around governance. Corruption scandals currently in the press have not buoyed confidence. Legislation is great on transparency e.g. the Petroleum Revenues Management Act, but less impressive on enforcing accountability in public service. Separating the role of the attorney general from that of the Minister of Justice and granting anti-corruption agencies such as the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice independent prosecutorial power would be important steps in that regard.

Nana Ampofo is a Partner at Songhai Advisory LLP

China is an example of a country that has stabilized itself via strong agricultural reforms. China’s initial attempt to industrialize, from 1978-1980 known as the Great Leap Forward resulted in famine and millions dead as the government imposed an Ag policy on farmers that did that provide them an incentive to produce.

This changed in 1980 when officials discovered some peasants in a local employing a contract system, which the government approved and adopted. This simple change in Ag policy resulted in an increase in Ag production by 47% while reducing the labor used by 19% within the first few years if it’s inception. China’s subsequent attempts to modernize were far more successful, as we see today. Britains agricultural revolution is an older example. A stable agricultural base is a vital first step to modernization.

Now consider India’s “green revolution” the sudden adoption of modern Ag technology that’s unaffordable for the population. They produce a food surplus while still maintaining incredibly high rates of malnutrition. This is because the government chose to empower foreign interest instead of domestic interest to increase its food production. There’s no stability to be had in a country that can’t feed its people on its own. Until that is taken care of the entre potential that the ghananian people represent will be locked away in the sustinance farm fields for another generation. And should the price of food imports increase or aid be modified, the Ghanaian governments authority becomes increasingly precarious. The breadwinners make the rules.

Ghana’s population is largely rural. When I hear Ghana speak about its economy it only discusses the private sector and exports while ignoring production in its rural sector. Ghana should focus on food production because it’s the most common venture among the Ghanaian people, who are ultimately the only ones who can build the infrastructure for their own country effectively. China’s leap came from encouraging domestic businesses and encouraging trade between them and the rest of the world. But no country has or ever will be allowed to build itself on the backs of another nations companies. If the Ghanaian government wants infrastructure, then it needs to find a way to get the Ghanaian people to build it.