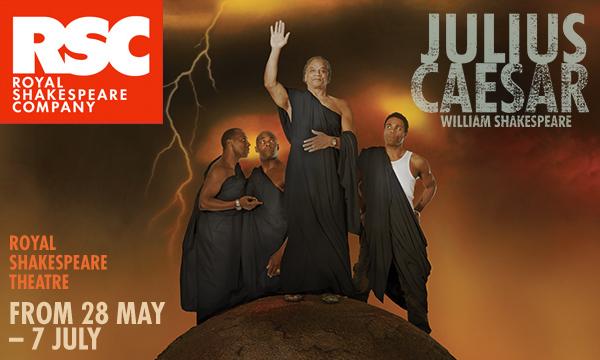

Shakespeare and Africa – Richard Dowden reviews an Africanised production of Julius Caesar

When I was asked to write the programme notes for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of an African Julius Caesar at Stratford-upon-Avon, I tried to imagine what it would be like. My first image was of African actors struggling to be like Romans speaking quaint 16th century English. It would be admirable but unconvincing. Black skins beneath white masks I had thought. An African Caesar would be almost as awkward as a European Othello.

When I was asked to write the programme notes for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of an African Julius Caesar at Stratford-upon-Avon, I tried to imagine what it would be like. My first image was of African actors struggling to be like Romans speaking quaint 16th century English. It would be admirable but unconvincing. Black skins beneath white masks I had thought. An African Caesar would be almost as awkward as a European Othello.

I could not have been more wrong. It was as if the play was written for those actors. Every gesture and intonation is African. So are the political themes: noble ideals leading good men to bloody murder, the coup against a tyrant followed by the falling out of the conspirators, petty jealousies, sly duplicity and secret plotting. All these themes have haunted African politics for half a century. Here are Idi Amin, Nelson Mandela, Robert Mugabe, Laurent Kabila and Colonel Gaddafi. Ashanti togas and wrap-around lappas make it even more authentically African as if the play was about a recent coup in Africa. An all European cast could only to the play as a re-enactment of ancient history. This African production is a news story.

Jeffery Kissoon is a diffident but effortlessly grand Caesar, Adjoa Andoh, a moving Portia and Ray Fearon, a convincingly cynical Mark Anthony. Cassius from the start is a scarily prowling outsider – lean, hungry – and lowering with hatred. Paterson Joseph as Brutus smiles and tries to please everyone but dithers over the big decisions. So his suicide is not quite convincing but that maybe Shakespeare’s problem rather than the actor’s. By the end of this production khaki guerrilla uniforms on the battlefield of Philippi are no more an anachronism than the clock that strikes in Act 2. This production has taken Julius Caesar out of time and place, made it global and timeless. This is a great production.

It will be travelling from Stratford all over the country between now and the end of October. Don’t miss it!

Here are my programme notes:

Hidden agencies

“If Shakespeare were with us now,” an African friend once told me, “he would have a much better rapport with me than with you.” He and Shakespeare, my friend explained, could talk about sacred groves and the power of spirits. Both of them could understand the raw paranoia of kings and lords and knew the horrors of anarchy and catastrophe. My cosy world, he said, protected, regulated, removed from raw reality, would not interest Shakespeare. What for many of us in Europe is Shakespeare’s world of poetry and metaphor is often hard reality in Africa.

Life for most Africans is closer to the way all human beings have lived until recent times. And somehow more intense, more immediate. The sun feels closer, the sky higher, the rain heavier. The earth is barren or absurdly bountiful. Diseases are more virulent and animals and bugs are bigger and more dangerous. Beggars and the disabled are on the street, in your face. Death is closer and when people die the coffin is open. The Western world feels grey and muffled in comparison, sheltered by screens, walls and windows. Our thoughts and language constrained by euphemism and political correctness.

The politics are fiercer too, matters of life and death. The gloves are off. Dictators like Mobutu Sese Seko and Robert Mugabe rise and fall like Shakespearean kings and lords. Others have started well and then, like Macbeth, became paranoid dictators. Shakespeare needs no explanation, no context setting here. The tribalism of Montagues and Capulets is instantly recognizable. So is the powerful magic of Prospero controlling the spirits of air, earth, water. Birth, life, power, war, integrity, duplicity and death, truth itself, are visible, tangible daily life in Africa.

Shakespeare knew something of Africa. Burgeoning trade with West Africa, increasingly in slaves, brought many Africans to London. Two years before Shakespeare was born Sir John Hawkins had grabbed 300 Africans from what is now Sierra Leone and taken them for sale in America. In 1590 the trade, increasingly in slaves, brought so many Africans to London that Queen Elizabeth issued an expulsion order. Shakespeare would have seen them go. He would also have probably talked with merchants and sea captains and Africans themselves and heard tales of the fabled wealth of Africa.

Today Shakespeare is taught in most schools in English speaking Africa. In a rural school in Uganda where I taught 40 years ago, almost none of the pupils had been to a town, let alone a theatre or cinema but Julius Caesar took Form 3 by storm. Idi Amin had just seized power in a bloody coup and random assassinations of powerful politicians were frequent. The plot against Caesar was instantly recognised. “Yon Cassius has a lean and hungry look” was quoted in every discussion, Cassius substituted by the name of whoever they were teasing. So did the Tribunes’ contempt for the crowd. They would greet their friends with: “Why, sir what trade art thou?” The teenage pupils had a natural feel for the plot and the drama. The crowd scenes were played effortlessly without rehearsal. They knew all about simple people duped by ‘tricky’ politicians. But above all they loved the language of Shakespeare, its rhythms and its formality – also a feature of their own language.

Most African countries inherited curricula from the colonial power; France, Britain or Portugal. Many governments wanted to put Africa at the heart of all school subjects. Literature had to be African literature. But somehow Shakespeare often survived. In 1989 the government of Kenya withdrew all non-African literature from the school curriculum as part of an Africanisation programme but President Daniel arap Moi, a former schoolteacher, stepped in and insisted that Shakespeare alone be kept on the syllabus. Shakespeare, he said, was a literary genius of universal acclaim.

Other African leaders have paid tribute to Shakespeare by translating his works into their own languages. Sol Platje, the founder of the African National Congress in 1912, translated some of the plays into Sechuana.

Julius Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania and a socialist, translated the Merchant of Venice into Swahili, though he substituted the word merchant for capitalist to suggest that Shylock was hated because he was a capitalist rather than that he was Jewish.

In 1970 in South Africa Welcome Msomi wrote a Zulu version of Macbeth, uMabatha. The witches translate directly as Sangomas, the powerful spirit mediums who foretell the future to a powerful warrior.

As Nelson Mandela said of the play: “The similarities between Shakespeare’s Macbeth and (Zulu history) become a glaring reminder that the world is, philosophically, a very small place.”

Mandela frequently quoted Shakespeare. In his memoires he recalls a rare meeting with his son Thembi, then aged 17, at which they discussed Shakespeare’s interpretation of Julius Caesar. Thembi later died while Mandela was in prison. Mandela recalled: “he gave me what I considered in the light of his age at the time, to be an interesting appreciation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar which I very much enjoyed”,

According to Anthony Sampson, Mandela’s official biographer, the culture and guiding text of the political prisoners on Robben Island from the 1960s to 1991 was not the Bible or the Koran but Shakespeare. Of course the prisoners were not allowed books but one of the Indian members of the ANC, Sonny Venkatrathnam, hid a copy behind some Indian religious paintings in his cell. The copy was passed around and the ANC members selected their favourite quotes. Prisoners later recalled that Shakespeare’s understanding of human courage, suffering and sacrifice reassured them that they were part of a universal drama.

Mandela chose lines from Julius Ceasar and signed it significantly 16th December 1977, the anniversary of the terrible battle of Blood River when the Afrikaners defeated the Zulus in 1838.

“Cowards die many times before their deaths,

The valiant never taste of death but once.”

He should know. In 1964 on trial for his life, he ended his speech from the dock on a Shakespearean note. “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities” he said. “It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

The programme is available from:

http://www.rsc.org.uk/shop/browse/