Sad South Africa: The Truth in Numbers and the Facts behind the Sentiment – By Desné Masie

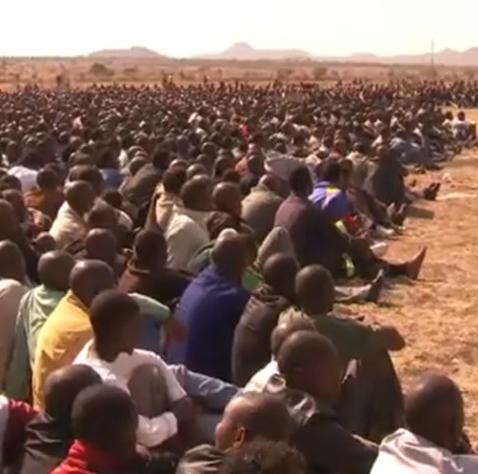

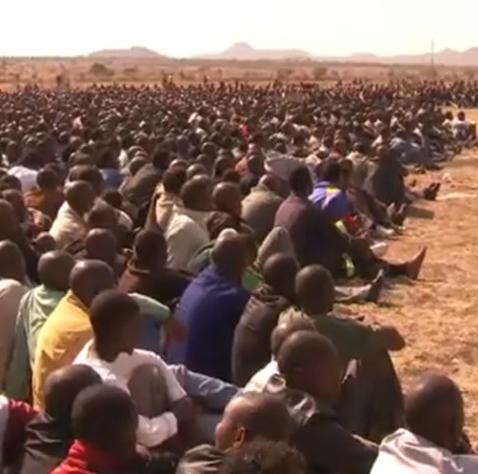

Striking miners in South Africa have tarnished the reputation of South Africa's economy, but it's not all doom and gloom.

South Africa is Africa’s largest economy, and a gateway to trade and investment on the continent. However, contrary to the “˜Africa Rising’ narrative I contextualise in my blog earlier this week, the Rainbow Nation has had incredibly bad press recently.

One of the most read articles in The Economist this past month has been the damning ‘Sad South Africa: Cry the Beloved Country‘. One of the main points The Economist makes is that South Africa is slipping while the rest of the continent is “clawing its way up”. Surely, if the continent’s largest economy and favourite democracy was indeed tanking, then this somewhat tempers the Africa Rising narrative?

Whilst there are some causes for concern in South Africa (which I discuss below) this is part of a growing volume of commentary that subjectively exhorts events and figures about the country with no regard for their context. Both Reg Rumney and Africa Check contend The Economist has first crafted a narrative, and then used the numbers to support it. Rumney writes here in ‘Cry the Beloved Cliché: “it’s an easy kind of journalism, make up your mind about the story and find the facts to fit”.

Luckily, the National Treasury of South Africa recently released a medium term budget policy statement and Statistics South Africa, the results of the 2011 Census, just in time to look at the facts behind the sentiment.

Lonmin Marikana – Not exactly a ‘Black Swan’

The Marikana strike at the Lonmin platinum mine in August 2012 saw 34 miners killed by the police, and South Africa’s image shattered. The medium-term budget policy statement for 2012 issued by its National Treasury estimates the strikes cost the economy about ZAR10BN and admits that the Marikana shootings and wildcat industrial strike action dented confidence in the country and will further slow growth in 2012.

South Africa has always been an important producer of precious metals, and while its mining sector is in decline, the minerals-energy complex is a significant component of the economy with implications for related industries. Business Day journalist Tim Cohen says Marikana is a ‘Black Swan’ – an outlier event with extreme effects. I disagree. The events at Marikana though extreme, are not likely to be repeated per se. But if South Africa’s volatile cocktail of inequality and joblessness does not receive meaningful and decisive action from the government, its stability will become threatened by this enemy within.

Understanding the Moody’s downgrade

The slower than desired socio-economic transformation and infrastructural development has led to a downgrade of South African sovereign debt one notch. But it remains an investment grade sovereign. This is still a pretty good situation to be in globally and in relation to the continent, especially for its growth and development prospects.

Ratings prospects for countries at the epicentre of the “˜Club Med’ Eurozone crisis are also dire. Most African countries still do not have ratings for their sovereign debt, and the majority of those that do are at junk bond status. Moody’s warned that “While the National Development Plan submitted by the country’s National Planning Commission last November formulated a comprehensive set of reforms meant to lead to increased development and reduced inequality, Moody’s notes that the fractious domestic environment is not conducive to the reforms being implemented at present.”

The Moody’s downgrade came perhaps a bit sooner than expected, but it is now in line with S&P and Fitch’s ratings. Hopefully the warning signal to foreign investors will get the ruling party to accelerate the National Development Plan (see my earlier piece on this) and increasing the scope of its successful social grants.

Moody’s explicitly warned the ANC to articulate a coherent macroeconomic framework at the election of its national executive at Mangaung: “The rating outlook remains negative because of the uncertainty surrounding critical policy decisions that will be made at the upcoming National General Conference of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party in December. The ANC’s National Policy Conference at the end of June left many such discussion topics unresolved. South Africa’s medium- to long-term political and economic stability depends crucially upon how well the party is able to coalesce the ongoing policy discussions into concrete and effective decisions by that time.”

Medium-term budget policy statement 2012

– Slowing GDP – South Africa’s real GDP slowed in line with trends in major economies and growth lagged slightly behind global GDP (3.3 percent) for 2011 at 3.1 percent. This is, however, much slower compared to China, estimated at 7.8 percent for 2012.

– Widening Current Account Deficit – The current account deficit has widened sharply over the past year and is expected to average 5.9 per cent of GDP in 2012, up from 3.3 percent in 2011.

– Slowing growth and sticky unemployment – The decline in GDP and the global financial crisis presents a challenge to South Africa’s strategy to create jobs through economic growth, as does the growing education crisis – which has seen South Africa fare dismally in maths and science education in particular. The unemployment rate remains stubbornly high at 24.9 percent – this is about the same rate of unemployment currently being experienced by Spain, which is in the grip of austerity and recession.

–Volatile currency – The notoriously volatile rand has been a perennial favourite of speculators in the carry trade (of interest rates), but this has been pronounced over the past year with diverging sentiment.

–Inflation – Core inflationary pressures remain contained and headline inflation is expected to stay within the reserve bank’s 3 to 6 percent inflation target band.

Results of Census 2011

In late 2011, South Africa undertook a national census, the main result of which was an increase in its population of 15.5 percent to 51m from around 44m over the past 10 years. This will put a significant strain on the country’s resources, particularly since service delivery by municipalities remains subpar. Disparities of income between black and white households remain extremely high, with the average black household income at around a quarter of the average white household. It is expected that it will take around 50 years for black households to catch up.

South Africa Loves Democracy

South Africa remains a leader on the continent largely due to its accountability and transparency, evident in the robust data it is able to produce and its vigorous media. It will not stop being a stable democracy with strong institutions without civil society putting up a big fight. South Africans love democracy.

Martin Plaut, former BBC Africa World Service editor told me in an interview earlier this year, that one of the remarkable qualities about this complex country, is “the way in which South Africa always comes back from an apparent knife edge”. Yet the country remains an enigma. It is a favourite with investors due to its substantial financial depth and sophistication, with a GDP close to Norway’s, and a member of the rising BRICS economies ranked most competitive by the World Economic Forum amongst all African Countries. However, though it also ranks as an Upper Middle Income Country, it simultaneously maintains one of the greatest disparities of income in the world – and this is the greatest inhibitor to South Africa continuing to fulfil its enormous potential.

There is a lot in South Africa to remain positive about, but I highly suspect there are currently several portfolios out there short on South African stocks, and this is an additional driver of prevailing sentiment.

Desné Masie is a journalist and academic.