Zimbabwe: heading towards elections without political reforms – By Simukai Tinhu

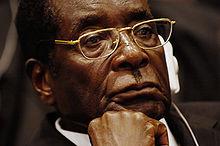

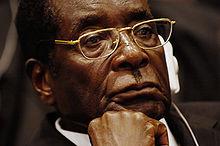

Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF has a history of using violence for political ends, there is no reasonto suggest the next election will be any different.

On the 16th March, the new constitution of Zimbabwe was approved by an overwhelming majority of voters. Ninety five percent voted “˜Yes’, and many, including the international community were encouraged by the relatively peaceful nature of the elections. The European Union (EU), without delay, proceeded to ease sanctions against targeted individuals, and organisations in Zimbabwe. This posture has been interpreted as a reward to the coalition government for reforming the political environment. Even the opposition, civic and human rights organisations expressed satisfaction with the election process.

But is the peaceful nature of the referendum a reason to celebrate and believe that contestation for political power in the June election will be greeted by the same political environment?

Certainly not. It is important to remind ourselves that the final draft constitution was never contested. Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU – PF); Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), and the smaller MDC party led by Ncube, were all in support of a “˜Yes’ vote.

With the return to “˜winner takes all’ politics at the end of the coalition government, the political environment is likely to be different. Tellingly, the arbitrary arrest of prominent human rights lawyer, Beatrice Mutetwa and senior officials of the MDC, days after the referendum, is the most aggressive sign yet that the political environment during the general elections will be tense. It is also ZANU–PF’s way of reminding voters, the opposition and the international community, that the party is not taking any chances in the upcoming elections.

Misplaced optimism that elections might be free and fair reveals a tendency, when analysing elections, to discount or forget that violence has been at the heart of ZANU–PF dominated politics in Zimbabwe. Indeed, a cursory scrutiny of post–independence electoral history reveals that a common theme of repression and violence courses through almost all elections.

In the run up to the first post–independence elections in 1985, fearing rebellion, the regime unleashed the “˜Gukurahundi’ policy against the supporters of Zimbabwe African People’s Union – Patriotic Front (ZAPU–PF), resulting in the deaths of thousands. In 1990, the Zimbabwe Unity Movement (ZUM), a party that provided the first serious challenge to ZANU–PF, claimed widespread intimidation and violence.

In 1996, the two political parties that contested ZANU–PF in the presidential elections, Abel Muzorewa’s United Parties (UP) and Ndabaningi Sithole’s Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU – Ndonga), withdrew from the election citing widespread irregularities, and intimidation of their supporters.

The emergence of the MDC in 1999 saw an opposition political party that had genuine prospects of unseating ZANU–PF from power. ZANU–PF’s response to this challenge was to unleash violence in 2002, and 2008, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of people.

In other words, violence is pervasive in ZANU–PFs’ political practice, and it shouldn’t therefore come as a surprise if this year’ elections are shrouded in violence, intimidation and repression.

Reforms off the Table

In order to ensure that subsequent elections would not be a repeat of the 2008 political battle, the government of national unity tasked itself with implementing political and electoral reforms. However, from its inception, the coalition government partners squabbled over how much reform was necessary before a satisfactory election could take place.

ZANU–PF insisted that there was no need for reform, and President Mugabe’s party was entirely confident that state institutions were capable of delivering valid elections at any time. On the other hand, the opposition and the civic community’s proposition was that there was need for extensive reforms as the minimum condition for holding elections.

Seeing no progress, the opposition gave up and concentrated on the constitution. As a result, many areas that badly needed reforms have been left virtually untouched. For example, there is still sporadic state–sponsored political violence upon civilians, journalists and political activists. In addition, state affiliated groups that were behind a lot of cases of torture, inhuman and degrading treatment of civilians in the run–up to the last two elections, such as war veterans and ZANU–PF youths are still intact.

Also, despite calls for reforms, the media in Zimbabwe remains muzzled, with only a handful of privately owned daily newspapers and radio stations. This has meant that public information remains under the firm control of ZANU–PF. On the other hand, the state media is still grotesquely unbalanced as ZANU–PF continues to use its control of state–owned print and electronic media to manipulate public opinion in its favour while using hate speech and other undermining language against the opposition.

The coalition government has also failed to make any changes to repressive laws such as the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA), the Public Order and Security Act (POSA), and the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act. These laws have been used to severely curtail basic rights through vague defamation clauses and draconian penalties.

But failure to make political reforms is a much smaller problem. The Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) and some analysts have called for reform of the military, police services, the state intelligence services and other critical arms of the security sector. This has been strongly resisted by ZANU–PF, which still retain full control of the security sector, the ultimate line of defence of its hegemony. For example, at its December 2009 party congress, ZANU–PF insisted that it would not allow security forces to be subjected to reform.

This is despite clear provisions in Article (xiii) of the Global Political Agreement (GPA) – a political arrangement that governs the business of the coalition government – stipulating that “state organs and institutions do not belong to any political party and should be impartial in the discharge of their duties.”

The fact that the security sector is still deeply embedded in the political affairs of the country, and that they still have a symbiotic relationship with ZANU – PF raises legitimate fears that this year’s elections could lead to a repeat of 2008 where ZANU – PF, in partnership with the “˜securocrats’ thwarted a democratic transfer of power. The securocrats have vowed not to accept other contestants as president – even if they were to win – contravening the GPA, and the codes of conduct of their won establishments.

In few cases where there have been political reforms, the quality and extent of those reforms have been minimal. For example, the newly created Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission could help improve the human rights environment, but its mandate is limited to investigating and reporting on human rights abuses committed after the unity government was formed in February 2009, excluding the widespread electoral violence of 2008.

Why the coalition failed to effect political and electoral reforms

The distribution of power within the unity government partly explains why there has been a lack of reform. Unlike under Kenya’s transitional government, where executive power was shared between President Mwai Kibaki and Prime Minister Raila Odinga, which enabled some key reforms to be undertaken, in Zimbabwe, President Mugabe never relinquished executive power, and as a result has been able to block required reforms. In addition “˜securocrats’ have used their positions and close relationship with ZANU–PF to veto reforms.

ZANU–PF’s capacity to block reform is not solely due to its hegemonic status in the coalition, but has also been aided by the opposition’s poor strategisation, coupled with a series of serious miscalculations. For example, the opposition walked into the coalition government without a strategy on how to coerce ZANU–PF into making necessary reforms. They also mistakenly counted on ZANU–PF to be a reliable political adversary with which they could do business.

Moreover, President Mugabe also manipulated the issue of sanctions and propagandised it as part of his efforts to frustrate political reforms. In response to human rights and election-related abuses perpetrated between 2001 and 2008, the US and EU adopted a variety of measures designed to promote reform. President Mugabe and ZANU–PF argued that reform was contingent on the removal of sanctions and accused Prime Minister Tsvangirai’s MDC–T of reneging on its GPA commitments to facilitate this. On the other hand, the MDC–T argued that it had no control over sanctions, and there would be a stronger basis for their removal if GPA violations ended, and ZANU–PF was not blocking reforms. This cycle of squabbling scotched prospects for constructive compromise on political reform.

Elections without Reforms

Having been unable to secure reforms in the last four years, the prospects of success within the next few months looks gloomy.

Remarkably, the civic community and the opposition still feel impelled to insist on political reforms before the next election. Some have even argued that the government of national unity should be extended, in order to give the coalition partners adequate time to undertake necessary reforms.

Political reforms are a large problem for ZANU–PF. They are unlikely to happen as they mean creating an environment that would force President Mugabe to abandon a sacred tradition that has aided his party’s electoral “˜victories’ since 1980; violence and repression. Faced with such a Hobson’s choice, the opposition needs to acknowledge that the electoral battleground in the coming elections will be uneven. Once they have accepted that, hopefully, the opposition will be liberated from complacency, forge an “˜opposition coalition’ and campaign very hard. Decisive electoral victory, which President Mugabe’s ZANU–PF cannot manipulate, is the only way to power.

Simukai Tinhu recently graduated from the University of Cambridge with an Mphil in African Studies.

[…] Zimbabwe needs to accept that the electoral battleground in the coming elections will be uneven and forge ahead with its campaign if its to have any chance of beating President Mugabe’s party, according to Simukai Tinhu. Tags: bailout, Cyprus, Europe, Eurozone, Germany, Pervez Musharraf, […]

[…] Zimbabwe needs to accept that the electoral battleground in the coming elections will be uneven and forge ahead with its campaign if its to have any chance of beating President Mugabe’s party, according to Simukai […]