Libya: Political, logistical and security problems challenge National Oil Company’s move to Benghazi – By John Hamilton

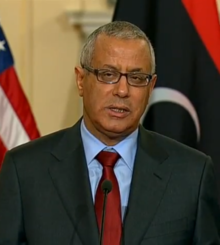

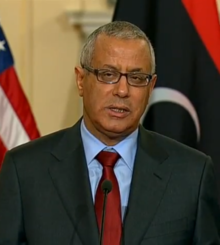

Libyan PM Ali Zeidan has pushed through the relocation of the National Oil Corporation from Tripoli to Benghazi.

The Libyan government’s decision to relocate the headquarters of National Oil Corporation (NOC) from Tripoli to Benghazi raises more questions than it answers. These include when and how the move will be made, what parts of the corporation will be relocated and what effect it will have on NOC’s still poorly defined relationship with the Ministry of Oil and Gas, and with its own joint ventures and subsidiaries.

The move will also have political and security ramifications for IOCs and service companies. For all these reasons, it is not likely to happen soon. Additionally, NOC will have to build a new headquarters for itself and one of Benghazi’s problems is that almost nothing has been built there since its population overthrew late leader Muammar al-Qadhafi in February 2011.

Eastern Libya’s oilfields account for two thirds of national production, but under Qadhafi Cyrenaica was neglected in favour of the western province of Tripolitania, creating longstanding resentments which the revolution’s aftermath has done little to appease. The move follows a series of strikes and protests at the lack of economic development in Cyrenaica. In December, union leaders in Benghazi threatened that NOC subsidiaries in the province would break away from central control unless the state company moved its headquarters to the city.

It is doubtful that NOC will shift to Cyrenaica in exactly the same form that it is now. What functions may be transferred raises a broader unanswered question about the role the corporation should play. Currently the top floor of its relatively new Tripoli headquarters is occupied by the new ministry – which will stay in Tripoli. The ministry is currently small, but could grow. It might therefore want to retain certain functions in the capital such as oversight, budgets, regulation, and even international marketing. No details have been released. The decision also does not address the desire for subsidiary companies in the upstream, downstream or service sector to have more autonomy. The Benghazi-based Arabian Gulf Oil Company (Agoco) is struggling to maintain production thanks to management failures combined with unsatisfactory budget allocations. If NOC moves east, how will this affect the internal relationship between these two entities, not to mention the various downstream, drilling, domestic oil marketing and service subsidiaries?

Already there are signs that officials favour parcelling out functions to different parts of the country to ease political pressures. On 10 June, Prime Minister Ali Zidan attempted to placate the southern region of Fezzan, issuing an order creating an oil refining company in Awbari authorised to build a 30-50,000 b/d refinery and a Sebha-based exploration and production company. The government had previously attempted to keep federalists in Benghazi happy with the offer of splitting NOC in two and moving its downstream headquarters to Cyrenaica. This was rejected by local politicians and unions.

The politics of the decision and its long term security implications are deeply intertwined. According to some reports, the government was pushed to announce the move after a group calling itself the Cyrenaica Transitional Council declared self-rule for the province. Federalism may not yet be supported by a majority of Cyrenaicans, but is growing in popularity thanks to central government’s failure to stimulate local development. Supporters of the relocation hope that returning NOC to eastern Libya where it was originally based prior to the 1969 Qadhafi revolution will boost the local economy, as IOCs and service companies with offices and depots in Tripoli will be obliged to move them to Cyrenaica. However, two days after residents of Benghazi celebrated the news of NOC’s return with fireworks, a stand-off between protestors and armed personnel from the Libya Shield Brigade – a militia auxiliary force attached to the National Army – led to fighting in which 27 people died. As a result, Army chief of staff Yousef Mangoush resigned. Most assessments suggest that Benghazi is significantly less safe than Tripoli. While this continues, most of NOC’s relations with IOCs and foreign service companies will remain in the west.

With political agreement, new infrastructure and buildings, a rebuilt sewage system and functioning security, Benghazi could one day become an ideal stopping off point for foreign workers on their way to Sirte Basin fields. However, for now little can change.

John Hamilton is a director of Cross-border Information, publisher of African Energy.

‘The Benghazi-based Arabian Gulf Oil Company (Agoco) is struggling to maintain production thanks to management failures combined with unsatisfactory budget allocations.’

Please can you tell where you got this information from?

The politics of the decision and its long term security implications are deeply intertwined. According to some reports, the government was pushed to announce the move after a group calling itself the Cyrenaica Transitional Council declared self-rule for the province. Federalism may not yet be supported by a majority of Cyrenaicans, but is growing in popularity thanks to central government’s failure to stimulate local development. Supporters of the relocation hope that returning NOC to eastern Libya where it was originally based prior to the 1969 Qadhafi revolution will boost the local economy, as IOCs and service companies with offices and depots in Tripoli will be obliged to move them to Cyrenaica. However, two days after residents of Benghazi celebrated the news of NOC’s return with fireworks, a stand-off between protestors and armed personnel from the Libya Shield Brigade – a militia auxiliary force attached to the National Army – led to fighting in which 27 people died. As a result, Army chief of staff Yousef Mangoush resigned. Most assessments suggest that Benghazi is significantly less safe than Tripoli. While this continues, most of NOC’s relations with IOCs and foreign service companies will remain in the west.

Ruth – I got the information about Agoco’s production problems and the reasons behind it having spoken to people at the company, a couple of Libyan energy consultants, and a source in the oil trade.