Are Zimbabwe’s Relations with the West Warming as Elections Approach? – By Simukai Tinhu

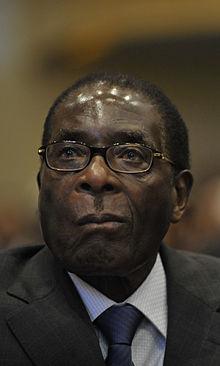

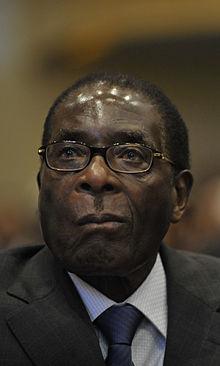

Western rhetoric towards Robert Mugabe seems to have softened slightly – perhaps due to the total failure of former tactics.

When President Mugabe unilaterally announced that Zimbabwe’s general election would be held on the 31st July this year, this seemingly provocative action was met with unusual silence by Europe and United States’ political class. This mutedness contrasts with reactions prior to 2008 when such an unprecedented move would have provoked an immediate and strong response from senior officials in Washington and Brussels, and certainly from a British prime minister.

Though this might not indicate an overarching change of policy, the international community’s indifference to such a major political development exemplifies what appears to be a broader phenomenon, namely, changing attitudes in the West’s view of the Zimbabwean polity.

In particular, the lifting of sanctions against some members of President Mugabe’s inner circle is the clearest indication yet that the international community is experimenting with reconciliation. Indeed, some of the Zimbabwean government’s aides were recently invited to London for a “˜reengagement meeting’. The EU and US apparently did so on the basis that there has been some progress on Zimbabwe’s political scene. But this rationale appears disconnected if one considers that there have been virtually no political reforms – apart from a seriously flawed constitution which ZANU–PF intends to violate or change soon after the July elections (which they have no intention of losing).

The Zimbabwe government has been reaching out to the West

One might argue that the Zimbabwe government has been making attempts to reach out to the international community. In particular (and commendable), the efforts of the Prime Minister, Morgan Tsvangirai, via his world tours have helped sanitise Harare. Indeed, there is no doubt that Tsvangirai’s party – the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) – has given the Harare government a friendly face. President Mugabe, though half heartedly and indirectly, has also been attempting to reach out to the West. For example, his rhetoric against the British government appears to have toned down as compared to the period in the run up to the elections in 2008.

ZANU–PF and Mugabe aren’t going anywhere

The US and Britain might have also accepted that President Mugabe’s party is unlikely to be going anywhere. Reconciliatory language could be interpreted as some level of acceptance that, contrary to analysts who dominate the discourse on Zimbabwean politics, ZANU–PF has support within the country. Indeed, surveys undertaken by Afrobarometer and Freedom House show that support for ZANU–PF surged in 2012. Phillan Zamchiya, a University of Oxford academic, explains that even if ZANU–PF were to lose the election, getting rid of President Mugabe might still be an impossible task as he will attempt to stay in power by hook and crook.

Thus, given that President Mugabe’s party is deeply entrenched in Zimbabwean politics, unrelenting and harsh criticism of his person and party by Washington and London risks driving Zimbabwe into the arms of other interested parties, in particular, the Chinese.

China’s increasing grip on Zimbabwe is a threat British’s influence in the country, and has also left most Western countries in the cold in the rush for Zimbabwe’s minerals. Not only have mining rights for the biggest diamond mine to be discovered in a century been given to Chinese companies, President Mugabe’s government has threatened to revoke mining licences on other minerals granted to Western companies.

So could the West’s change of tack in its relations with the Zimbabwe government be seen as a demonstration of realpolitik in order to get access to Zimbabwe’s mineral wealth? There is nothing new (or particularly surprising) about states pivoting their policies to fit their interests. It is a common and acknowledged practice in international relations.

Opposition Parties’ Fraying Image

It is uncontroversial to observe that the Western support the opposition enjoyed in first 10 years of its formation has thinned out since the MDC-Tsvangirai and its smaller formation headed by Welshman Ncube joined the coalition government. This can partly be explained by the MDC’s fraying image as a result of corruption and undemocratic practices in its internal workings.

Also, a desire to not want to be viewed as hypocritical by constantly criticising President Mugabe and his party for the same practices that the opposition are guilty of, may explain why the West appears to be taking a more “˜hands-off’ approach with Zimbabwean politics.

Change of government in London and Washington

There is little doubt that Prime Minister Tony Blair and President George W. Bush, through the Zimbabwe Economic and Democracy Recovery Act (ZEDERA), were the main architects of the policy that saw President Mugabe’s government become a pariah state. Tony Blair’s relentless lobbying of the EU persuaded the Brussels-based organisation to impose sanctions against President Mugabe. His successor, Gordon Brown, intensified the attempted defenestration of Mugabe’s regime.

When the current conservative government took over, David Cameron quickly faded into the background on Zimbabwe policy. Today the EU (without intensive lobbying from London), has become circumspect in its criticism of President Mugabe’s policies. Indeed, some of the most senior Tory officials have been cited using a conciliatory tone towards Zimbabwe. The British coalition government’s lack of interest in Zimbabwean politics reflects the genesis of its government’s younger legislators who have little inclination to engage seriously with Zimbabwean politics, and also Westminster’s preoccupation with internal problems such as the economy.

More Faith in President Zuma of South Africa?

The former President of South African, Thabo Mbeki, who was tasked with resolving the political crisis that engulfed Zimbabwe between 2001 and 2008, pursued a softer policy towards President Mugabe’s government, dubbed “˜Quiet Diplomacy.’ This policy was heavily criticised by the EU and US, with Mbeki seen as reluctant to put pressure on his fellow “˜revolutionary cadre’ to institute political reforms. It appears that Britain and the US were unable to rely on President Mbeki to referee the political situation in Zimbabwe, leaving the two powers with no choice but to directly deal with the government.

In contrast, President Jacob Zuma has been more assertive in the conduct of his foreign policy towards Zimbabwe. In this regard, he has been supported by President Obama. Indeed, in his most recent trip to South Africa, Obama praised Zuma’s administration for reining in ZANU–PF, and for confronting them on numerous issues such as violence and intimidation, and lack of progress on electoral reforms. As a result of this confidence, Washington and Brussels have taken a hands-off approach and left President Zuma to take a lead role on Zimbabwe.

Lessons from Kenya

The other argument proffered is that criticising President Mugabe, and openly supporting other political parties as in previous elections, risks accentuating the influence of anti–western rhetoric (already significant) in Zimbabwean politics. This could create a similar situation as in Kenya, where ill-timed statements by British and American officials – warning Kenyans against voting for someone wanted by the ICC – were seen as an attempt to micromanage Kenyan politics. Uhuru, the ICC indictee, used these statements to run an anti-Western campaign, credited with contributing signioficantly to his (eventual) victory.

Thus, fresh attempts to defenestrate President Mugabe and his party and at the same time portray opposition leaders as saints, could be interpreted as giving endless fodder for stoking nationalism and anti–western rhetoric – favouring President Mugabe. By dropping the tactic of publicly criticising ZANU–PF, one could argue that Washington and Brussels are depriving President Mugabe of ammunition to take on opposition parties as imperialist agents.

But relations may change for the Worse any time

For the last 10 years, EU and US officials have placed a burden on President Mugabe’s government to stop human rights abuses, corruption and an to end political violence before they could rehabilitate his government back into the international community. However, despite having seen no political reforms; judging from the lifting of sanctions, toned down criticism, and some conciliatory language used by the two powers, it appears the substance of the relationship between Zimbabwe and the international community is changing.

Rather than confrontations, the EU and US have been attempting to manage the differences that they have with the Zimbabwe government. But this does not mean that the era of tense relations with Zimbabwe have come to an end. Given the chaotic nature of Zimbabwean politics at the moment, a more difficult and potentially dangerous situation is likely to result after the elections and the US and Britain might be forced to change their stance again.

Simukai Tinhu is a political analyst based in London.

Interesting the way the words EU, US, and west are used interchangeably with ‘international community'(and you are not mistaken to do so), which is exactly the point, isn’t it? ‘international community’ is a shrunken old vixen with a big mace, who likes to crush the heads of hapless lesser souls that do not bow to her whims. We should find a suitable word for the vast swathes left out of ‘international community’ maybe call them ‘rest of community’…Interesting article by the way. I have one word for you: CHINA