Britain and Africa: time to put the politics back in – By Julia Gallagher

Chris Mullin has accused me of “˜over-analysing’ Britain’s approach to Africa in his review of my book. I don’t disagree with him when he suggests that Blair and others were motivated substantially by idealism in their Africa policy. But I disagree strongly with his suggestion that we leave it at that. It is when politics is shaped by apparently self-evident truths that it’s at its most problematic.

Chris Mullin has accused me of “˜over-analysing’ Britain’s approach to Africa in his review of my book. I don’t disagree with him when he suggests that Blair and others were motivated substantially by idealism in their Africa policy. But I disagree strongly with his suggestion that we leave it at that. It is when politics is shaped by apparently self-evident truths that it’s at its most problematic.

Consequently it is important to examine the Blair government’s fascination with “˜doing good’ in Africa – to explore why its members could unthinkingly label a whole continent “˜a scar’, distinguishing it from “˜politics as usual’, and why this approach seemed to resonate across the political spectrum and with large elements of the public.

The book draws on interviews with 50-odd politicians and civil servants all of whom worked on Africa in one way or another between 1997 and 2007, including government ministers, backbench MPs working in All-Party Parliamentary Groups on Africa, and FCO and DfID officials. Strikingly, they all told a very similar story: that Africa policy was not about British interests, that being involved in Africa offered far higher job-satisfaction than other policy areas – the chance to make “˜a real difference’.

For many, like Mullin himself, Africa was the one government activity where they could fulfill the idealistic ambitions that had brought them into politics in the first place.

As Mullin picked up in his review, the idea of Africa policy as “˜pure’ was not new. It drew on a long history of British engagement with the continent that can be traced back to the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 – described by one historian as “˜among the three or four perfectly virtuous pages comprised in the history of nations’ – the establishment of Sierra Leone as a home for slaves freed by the British navy which patrolled Africa’s west coast after abolition, and the popular view of colonialism as bringing peace, and moral and intellectual enlightenment to the continent.

Later on, parts of the British Left became heavily involved in the anti-colonial struggle, idealising African heroes such as Kwame Nkrumah, Seretse Khama, Kenneth Kaunda, Julius Nyerere and Nelson Mandela. New Labour’s idea of a grateful African poor which secretly yearns for the return of benevolent colonial rule, is a continuation of this story. Mullin himself, who was minister for Africa in the Blair government, states this view explicitly in the book when he talks about the way in which Liberians long for a “˜modern colonialism’.

For many Britons, Africa represents a place where bad things can be healed – a “˜sacred space’ onto which the country could project the “˜good state’ – and it was this perspective that Blair represented. But it depended on creating an image of Africa as a “˜politics-free’ zone. It has to be imagined as populated with villains and heroes – Robert Mugabe, Charles Taylor, Sani Abacha on one side; Nelson Mandela and the African poor on the other. British policy was directed at encouraging the “˜progressive, good guys’ in their struggles with “˜the bad guys’. African actors and causes were flattened, presented as “˜good’ and “˜evil’.

As a result, Blair’s government largely failed to take account of the nuances of political relationships throughout the continent. That’s why the re-election of Robert Mugabe, and the support for him from fellow African leaders didn’t make sense. It was why Thabo Mbeki, the politician-president was a more problematic partner than Nelson Mandela, the saint-president. And it was why apparently heroic, progressive leaders like Meles Zanawi, Paul Kagame and Yoweri Museveni caused perplexity when they moved to crush opposition parties and control the media.

This inability to see the complexities of African politics and relationships allowed New Labour to pursue one of its key ambitions, to build and strengthen “˜capable states’ and “˜good governance’. Politics and governing were viewed as a technical exercise, one that could be taught through the transmission of a few simple rules and processes. Complex state-society relationships were misunderstood, while few stopped to ask whether developing state capacity and accountability is something that can be achieved by donors from abroad, no matter how well-meaning.

This approach – from Wilberforce to Blair – was always more about Britain than Africa. Africa policy mattered because it represented a “˜pure’ activity that transcended politics. For Wilberforce, it fitted an ambition to attach himself and the whole country to an important moral cause that transcended party lines; for Blair it met an aspiration to build “˜big tent politics’ which drew everyone together – from disaffected leftwing backbenchers to David Cameron. Africa didn’t involve messy political arguments.

Labour’s legacy on Africa has been to establish an idea of British policy as pure and disinterested, and above all, capable. The current Conservative government remains partly attached to this approach. Cameron early on sought to identify his party with the idealism of the “˜wrist-band generation’ most notably by ring-fencing DfID’s budget. He has spent considerable efforts trying to resolve the Somalia situation, and made principled and rather ill-judged interventions on anti-homosexuality laws in Uganda and the International Criminal Court in Kenya.

But the current government has also made substantial shifts in emphasis towards prioritising British trade interests (seen as absolutely key in the relationship with booming countries such as Kenya) and in tackling the apparently growing terrorist threat from parts of Africa. Here, policy is far more overtly being run along conventional national interest lines.

I see these shifts as positive. In acknowledging British interests they have the potential to treat African countries as complex political entities. Such an engagement is likely to be messy and difficult, and to expose the limits of British capacity – in other words, to become more like international relations everywhere else. It could foster more mature relationships than the historical tendencies that treated the continent as an exceptional space upon which Britain can demonstrate its goodness.

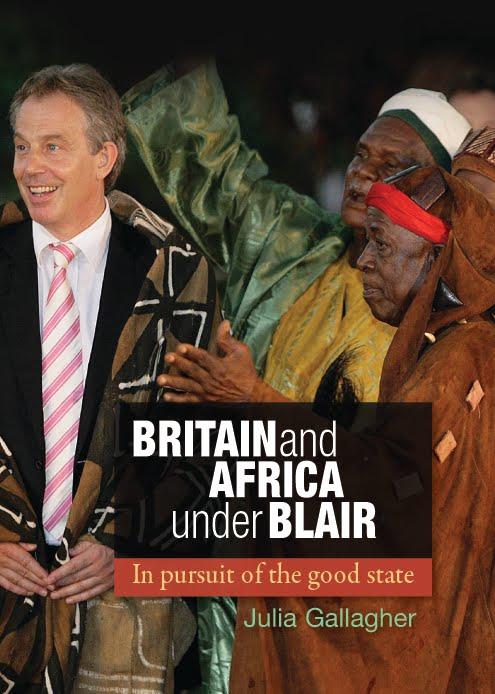

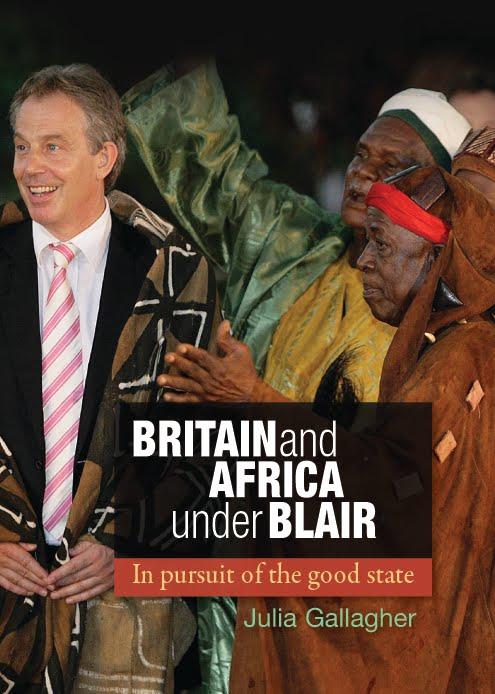

Julia Gallagher is a lecturer in international relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her book, Britain and Africa under Blair: in pursuit of the good state (Manchester University Press), will be issued in paperback later this year.

As I recall it, the founding of Freetown was to rid London of its black population and the abolition of the slave trade (or at least slavery itself) was made possible by the rise of the slave trade.

Britain also did not hesitate to replace African slave labor with that of Asian servants.

These strands seem to as much be acknowledged in the writer’s mentioning of a yearning to reestablish benevolent colonial rule, which seems to clash with the thesis that Africa policy is a ‘pure activity’.

Are the people who educated Robert Mugabe and brought us Garfield Todd that pathetically idealistic?

And I used slave trade a second time where I meant to say industrial revolution.

Ms. Gallagher, Thank you for your article. Western politicians may indeed have an altruistic streak on occasion. In the political dance of politician and constituency though isn’t it the ideas and perceptions of the electorate that lead? Isn’t it exactly the popular misconceptions fueled by a skewed narrative perpetuated by NGO’s and pop stars that gets the most hits. Received wisdom is subtly changing. Discussions such as yours are starting to have a main stream effect. In the future the narrative of a more well understood Africa should help the politicians get it right. Mike

Mr Chambers…altruism in whose perspective? I can hardly call a few million pounds spent on the starving or malaria or fgm or whatever else one wants to champion in Africa these days altruistic when I think about all the lost opportunities in trade due to the unjust and insane trading system imposed by the west on Africa and other poor places, when I think about the countless western multinationals aided and abetted in their plunder of Africa by these selfsame ‘altruistic’ countries, when I think about the support for despotism, the murder of revolutionary African leaders, all for the sake of western interests, the constant thwarting of African effort to wrest economic freedom from the grip of the powers that be…I think these gestures are only to impress western publics, and to buy and maintain influence in Africa and other far off places that must, to the western mind, forever be controlled. As an African, I remain thoroughly unimpressed most of the time, because I know there is so much more that these countries can do to reshape the order of the world we live in and thus, help Africans and other poor nations improve their lot, if only they were altruistic enough…but rhetoric and appearances are more important. The one thing I agree with this article is that Africa is a complex place…now, what has taken the western world, particularly its leaders and its journalists so long to come to this realisation?! what I can tell you is that its not just those who got enslaved and colonised that have historical baggage. The western world’s enduring negativity to and pessimism towards Africa and Africans, particularly black Africans as demonstrated in the almost automated switch between paternalism and deep-seated racism is its enduring baggage. Question is, do you really think these shifts the author is alluding to will last beyond the current urgency to contain Chinese influence on the continent? methinks not.