Kenya needs a comprehensive exit plan in Somalia – By Abdullahi Boru Halakhe

Kenya’s intervention in Somalia in October 2011 came as a surprise to many Horn of Africa observers. According to the Kenyan government, the raison d’íªtre for intervening was to pursue Al Shabaab members who allegedly abducted aid workers in Northern Kenya and kidnapped tourist along the coast.

Initially this sounded plausible (and even reasonable) given the genuine security threats posed to Kenya by Al Shabaab. But shifting dynamics in the port city of Kismayo raise questions regarding the changing goal of the occupation. Recent events reveal Kenya is keen in establishing a “sphere of influence” through Jubaland, putting the Al Shabaab theory to a stern test.

Since the intervention, the blowback has been evident – there is a deteriorating security situation along the border with Somalia, and in Nairobi there have been a series of grenade attacks. Whilst some of these have been the work of opportunistic criminal and business groups, others like the attack on the church in Garissa, bear the hallmark of Al Shabaab (and have been claimed as such through their twitter handle.)

Liberators or occupiers

Striking a somewhat righteous if not opportunistic posture, many Kenyans supported the intervention uncritically. And the initially triumphalist note prevented many from asking questions about the entire enterprise.

But the “altruism” explanation seems to be wearing thin against naked realpolitik displayed by the Kenya Defense Forces in Kismayo and its single minded determination to establish a sphere of influence in Jubaland.

There is an obvious rationale for wanting to control Kismayo – the strategic port is the nerve center of sea trade, and when it was controlled by Al Shabaab it provided the group with ready income. But taking full control of Kismayo has not been a straight forward affair due to several interlocking and competing interests. This is where Kenya needs to be cognizant of Somalia’s history and the radioactive nature of internal Somali clan dynamics (especially for an external actor like Kenya with questionable finesse.)

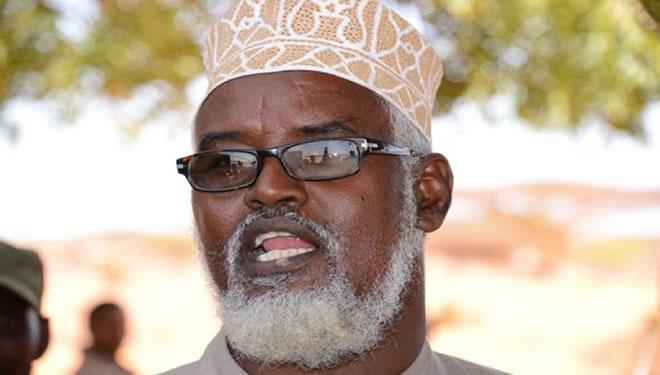

Kenya now seems to be walking straight into the local clan politics with its eyes wide open, particularly as a result of their support for Sheikh Ahmed Madobe, and by extension his clan, at the exclusion of the government in Mogadishu, which until recently was at loggerheads with Madobe.

Recently, a rather misguided and naí¯ve display saw Somali Ministers from the Central Government mistreated when they visited Kismayo – a move intended to undermine the authority of the new president. All the talk of federalism has become a self-fulfilling prophesy and masks the nefarious interests of Kenya which has aligned itself with Madobe and his clans. If the people in Kismayo want a devolved authority that is nominally answerable to Mogadishu, but autonomous at the same time, then that discussion should be left to the Somalis themselves. Trying to influence such an outcome is counterproductive and dangerous in the long run. If devolution is nothing but Kenya’s attempt at establishing a satellite state remote-controlled from Nairobi, then this reeks of sheer opportunism.

A recent rapprochement in Addis Ababa between Madobe and Mogadishu over the key outstanding issues is, however, commendable as tensions between the two sides were threatening to escalate. To make the deal, both sides made some concessions – the federal government recognized Madobe as the interim leader, and in return, the port will be handed to the federal government after six months. However, there is a caveat regarding the revenues generated by the port – priority will be given to the security and institutional building of the Jubas. Regarding security, the Ras Kamboni militias will be absorbed into the Somali National Army, although the local administration will be responsible for police and law and order issues. Remarkably, no timeline was set for this integration.

Wither Al Shabaab?

The only real beneficiary from the above mess is Al Shabaab, whose stock in trade for recruitment is the weak central government. Al Shabaab also bills itself as the vanguard of Somalia against external forces – the mere presence of Kenya inside Somalia is a perfect storm for the group; it will provide them with a raison d’etre to “˜liberate’ the country from the infidels. This will potentially undo any gains made since intervention and demonstrate Al Shabaab’s ability to transcend clan divisions.

Acute internal contradictions within the group are of greater existential danger than any external interventions – the pan-Somali nationalism espoused by Aweys and the transnational jihadist wing of Godane (nom de guerre of ‘Abu Zubeir’) was difficult to reconcile. The recent departure of Sheikh Aweys (regarded as the father of the jihadi movement in Somalia), the alleged killing of Ibrahim al-Afghani and fleeing of the group’s spokesman Mukhtar Robbow, reveals a serious power struggle within the group. But what is going on in Kismayo gives the group a second chance, similar to the 2006 Ethiopian invasion.

On the humanitarian front, as a demonstration of how tenuous the security situation is, recently, after decades of working in Somalia, Medicin Sans Frontiers (MSF) announced it was leaving. In a statement, the MSF said, “We are ending our programmes in Somalia because the situation in the country has created an untenable imbalance between the risks and compromises our staff must make, and our ability to provide assistance to the Somali people.”

Their departure raises serious questions about the regional interventions (Kenya, Ethiopia etc) and the attendant wave of good news coming from Somalia since they took place. This has seen Somalia once again on the international radar; two international conferences in London, countless visits by foreign dignitaries saying this is Somalia’s moment and many triumphalism stories in the news media – opening of beech restaurants, ice cream parlors and theaters. But all this gives a false impression that the country has finally left its chaotic past behind and underplays the one significant weakness that all previous Somalia governments had to contend with – the lack of the monopoly over the use of force. Without an army and a police of its own, peace and security will always be tenuous in Somalia.

In an effort to rebrand and remain relevant, on Eid, which marks the end of month of Ramadhan, Al Shabaab released through its media wing, Al Kataib, the video, “The Path To Paradise”. The 40 minute long video chronicles the lives of young recruits from Minnesota who joined Al Shabaab. The major theme of the video revolves around the evils the West is perpetrating on earth, and calls on every Muslim to participate, as a religious duty in defeating the Kufars (infidels.)

For Kenya, the lack of clear timetable for withdrawal from the outset was problematic because it provided a sort of open-ended commitment, which will inevitably fall prey to the ever lurking danger of mission creep. The window when Kenyans troops were regarded as liberators has long been closed and with it the goodwill of the Somalis. An indefinite stay and interference in Somalia’s internal politics will make the AMISOM mission in Somalia – billed as “˜Africa’s solution to Africa’s problem’ – look like an occupation.

Abdullahi Boru Halakhe is a Horn of Africa Analyst.