“Find some starving Africans”: Reporting Disasters – the nexus of crisis, NGOs and the media – By Keith Somerville

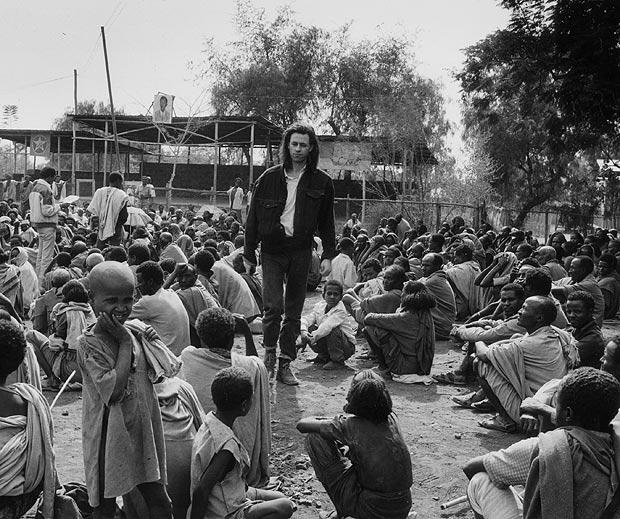

I’ve become very bored with the endless and usually unwarranted use of the word “˜iconic’ to describe people or events, but I have absolutely no argument whatsoever with Suzanne Frank’s opening sentence: “The BBC coverage of the Ethiopian Famine in 1984-85 was an iconic news event”. It was. Whatever questions remain about what Michael Buerk’s report from Korem omitted or how it was framed, it was a seminal moment in news reporting of humanitarian crises, of the global imaging of Africa and was to have consequences for NGO operations, NGO-media relations and the corporatization of the aid industry. Franks, in a balanced, informed and comprehensive account of the episode, succinctly examines the key developments that followed Buerk, Band Aid, Live Aid and the resultant beatification of Bob Geldof.

Franks is honest in her judgements and utilizes a massive amount of material that is in the public domain but has not, until now, been sufficiently correlated and analysed. Drawing not only on BBC and other journalistic accounts of how the story was broadcast, she also incorporates the valuable work of Amartya Sen on media, democracy and famines and the forensic critical analysis of famines and humanitarian responses by Alex de Waal.

Combining her experience at the BBC with her academic skills, the author narrates the development of the story and its massive impact – “almost a third of the adult population of the UK” watched the Buerk film (p.1) and it was rebroadcast over the next few days by over 450 TV stations worldwide, causing a wave of outrage and a massive desire to help. Media and celebrity involvement in alerting people to famine or humanitarian crises was nothing new (the example of Biafra is given in the book and one can think of George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh) but the response to the Korem film was a new departure in public reaction, scale of donations and the global NGO operations to which it gave rise.

However, at the heart of this work are the misconceptions, stereotypes and the consequences which hugely affected and still affect people’s understanding of humanitarian disasters and government responses. These sprang from the coverage of what now we identify as a questionable humanitarian effort. Whilst it was altruistic and thoroughly well-intended, it was also ill thought-out and, in the view of many like de Waal, reached only a small proportion of the starving, whilst propping up the violent and autocratic Ethiopian government. This consequently aided its brutal resettlement programme and consequently creating a greater level of suffering than it alleviated.

The obscuring of these shortcomings is examined fully in the book, as is how the public perception of the success of the humanitarian effort, coupled with the almost euphoric feel-good factor it engendered, fundamentally changed the NGO world. This lead to its growth “at an unprecedented rate”(p.2), distorting the relationship with the media in a way that has permanently altered the portrayal of humanitarian crises and of Africa as a whole. It has also given rise to what, with the rise of social media, has become the “˜clictivism’ and “˜slacktivism’ culture that has reduced people’s willingness to inform themselves of the nature and causes of crises – distorting and limiting responses and attention spans.

In lots of ways, the Ethiopian events precipitated a huge rise in charitable giving, the development of “˜the humanitarian response’ and of transitory concern as a Western lifestyle choice. This also saw the increasing prominence of NGOs as trusted voices and the growth of a decidedly “˜corporate’ character with a stake in massive and very carefully focused media coverage of crises. The “˜bought the CD, got the T-shirt, solved Africa’s problems approach’ was developed in this context-free environment. Franks argues that the Ethiopia 84-5 coverage was not only located in, but hugely contributed to, problems of the “superficiality of reporting, the lack of context or background, the reliance upon stereotypes” that bedevilled and still bedevil the reporting of Africa (p.9).

The book is analytically rigorous and does not pull its punches, taking the reader through the development of the famine and its reporting. It analyses the stunningly effective but context-free Buerk report – a masterwork in emotive and atmospheric television, but perhaps not of a journalistic rigour and detail enabling viewers to understand how, why and where the famine was occurring.

Michael Buerk, in an interview with the author, admits that in 1984 he had been instructed by the BBC foreign desk “to find some starving Africans”, partly in competition with a documentary being prepared by ITV and to provide what he called “a cheap and cheerful news piece”. What resulted was a stunning piece of writing, filming and production, but one that presented the famine as a sudden event (it was certainly not), an unexpected one (the Ethiopian, US and British governments and UN agencies were aware of the levels of starvation and food denial in northern Ethiopia) and as caused by drought (which it was not).

The book moves the focus on from the famine reporting to the development of humanitarianism as a celebrity and media-driven industry – is suffering in Darfur or DR Congo only serious if Clooney, Jolie or Madonna are there? Maybe we shouldn’t worry about this – would people know about Darfur if it was not for them? Would people know about the LRA if it was not for the questionable Kony 2012 video? Is some coverage, however flawed, better than none? This is hard to answer, but often the answer has to be that coverage that is so free of context that it elicits public and political responses that are positively harmful, can be worse than no coverage at all. Ill-informed meddling can be far more dangerous than non-intervention.

This is a dilemma of which Franks is well aware and I cannot argue with her conclusion that the Ethiopian famine coverage was an “exceptional episode in foreign news reporting” but it “highlighted the terrible paradox that the sight of faraway suffering might motivate thousands of individuals to offer their help, but these good intentions are not enough and could do even more harm than good” (p. 178). Quoting Richard Dowden, she warns of the dangers of the poisonous pact (p.146) between NGOs and journalists – one that is increasing as commercial, competitive and other pressures force the media, and broadcasters in particular, to cut back on foreign reporting staff, investigative journalism and the use of regional experts, and rely more and more (as Nick Davies wrote in Flat Earth News (http://www.nickdavies.net/books/) on press releases and the media output of people other than journalists.

NGOs have their own objectives in their media reporting – to highlight humanitarian crises or development needs and to elicit donations or compete for government aid contracts. But these are not the objectives of balanced and informed journalism; they can feed into it if journalism is questioning and incisive, but not if it just uncritically reproduces NGO PR.

This is an important book not just for the study of the Ethiopian famine, the role of NGOs and media coverage of humanitarianism, but for the study of the framing of Africa in the media and popular opinion. It should be on reading lists for courses on foreign reporting, African studies and communications.

Keith Somerville is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London; teaches Humanitarian Communications in the School of Politics and International Relations and the Centre for Journalism at the University of Kent; and publishes and edits the Africa – News and Analysis (www.africajournalismtheworld.com) website.