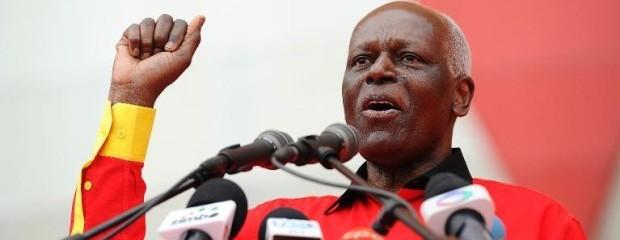

Angola: Violent repression of peaceful protests highlights risks of dos Santos succession – By Jon Schubert

Angolan President dos Santos’ skilful nurturing of party-internal rivalries has made it impossible for a “˜natural successor’ to emerge.

On Saturday, 23 November, Angola’s capital, Luanda, awoke to a “˜state of siege’. Government security forces invaded the headquarters of the largest opposition parties, and used tear gas to impede a peaceful protest demonstration from gathering. Over 300 people were arrested on that day, and at least three were killed, including Manuel Hilberto de Carvalho “˜Ganga‘, a leader of the youth wing of second-largest opposition party, CASA-CE. Heavily armed police also impeded any protest gatherings in the provinces, and surrounded UNITA headquarters in Bié, Bengo, Benguela, Cabinda, Cunene, Kuando Kubango and Namibe. However, international media attention has been eclipsed by the news that Angola was the “˜first country to ban Islam’ and that authorities had started demolishing mosques across the country.

Background

Since the end of its decade-long internal conflict in 2002, Angola has been internationally fíªted as a miracle of post-war reconstruction and economic growth, attracting investors and economic migrants from across the African continent and the entire world. However, there is a flip-side to this euphoric but rather uncritical “˜Africa rising’ narrative of the “˜New Angola’. Under the leadership of the “˜architect of peace’, President José Eduardo dos Santos, in power since 1979, the ruling MPLA party, is skilfully managing this reconstruction, tightly regulating the spaces for the expression of dissent, and restricting democratic freedoms. Despite the centrality of oil-generated wealth both to regime maintenance and this infrastructure reconstruction, a large majority of the urban and rural population remains excluded from economic growth and the “˜benefits of peace’; Angola has thus justly been cited as a paradigmatic case of “˜illiberal peace-building‘.

Since March 2011, increasingly vocal youth protests against the 34-year rule of President José Eduardo dos Santos started questioning this post-war status quo of “˜stability and reconstruction’. Emboldened by these initially very small youth protests, opposition parties began to find their voice and formulate alternative political visions for the August 2012 general elections. And war veterans, both from MPLA and UNITA, demobilised in 1992, also protested for the payment of overdue pensions. However, all these peaceful demonstrations were met with increasing police violence. Although Angolans and observers were bracing for the worst, the elections were largely calm; the MPLA took 71% of the vote, while UNITA doubled its representation in parliament to 32 seats; CASA-CE gained 8 seats, amid large voter abstention, voter disenfranchisement and apathy.

During these events in 2012, two veteran activists, António Alves Kamulingue and Isaías Cassule disappeared. Thanks to tireless campaigning by their families and Luanda’s youth protesters, the issue was kept alive until, two weeks ago, a document was leaked from the Minstry of Interior that detailed in gruesome detail how the two activists were abducted, tortured, and killed by members of the Angolan security and intelligence service, SINSE, and their bodies thrown into the crocodile-infested Bengo river. Following the public outcry, authorities reported that four SINSE officers were under investigation for the killings and President dos Santos dismissed the head of SINSE, Sebastií£o Martins, a move seen by Angolan commentators and the public at large as the vacuous sacrificing of a scapegoat, considering that the “˜real mandatory’ of the killings was either dos Santos himself, or one of his confidantes in the powerful Security Cabinet of the Presidency.

Unsatisfied with the government response, UNITA called for a peaceful demonstration on 23 November, which opposition parties CASA-CE, PRS, and Bloco Democrático endorsed. The authorities followed their by now standard course of action: the police strongly warned against any “˜illegal’ demonstrations, even though the right to demonstration without previous authorisation is enshrined in the 2010 constitution. The MPLA’s political bureau condemned the killing of the activists as a “˜criminal act’ but also discouraged the population from joining the demonstration, denouncing the “˜irresponsibility’ of UNITA for attacking “˜the country’s highest Magistrate, his Excellency the President of the Republic, José Eduardo dos Santos’ which threatened to “˜drag the country back to war’.

The state-owned media, fronted by the regime’s attack dog, Jornal de Angola’s editor-in-chief José Ribeiro, said although freedom of expression was an inalienable good of democracy, no one could ignore the will of the majority or question the independence of the judiciary. Finally, the MPLA’s youth wing, JMPLA, “˜discovered’ that its founding anniversary was, in fact, 23 November, not as previously thought (and celebrated) 14 April. This gave the police a further excuse to “˜prevent disruptions’ of the JMPLA rally, which had allegedly been announced to authorities much earlier than UNITA’s “˜irresponsible’ protest march.

Fallout

The public apathy that marked the post-electoral political climate has been shaken up by the confirmation of the killing of two activists, which may well be the tipping point for larger demonstrations. A younger, increasingly well-educated generation is coming of age that scarcely remembers the privations of war and is less easily satisfied with the “˜crumbs’ from the master’s table. Now that opposition parties are capable of formulating alternative policy visions and of capturing a significant part of the vote, the planned local elections will be a litmus test for Angola’s democratic institutions. So far, however, these have been delayed from 2014 to 2015, officially for technical reasons, so that a census can be conducted first, but most likely because of the serious, growing dissatisfaction with the MPLA’s performance in the cities. And the current reactions to demonstrations show that the ruling party will be very unwilling to relinquish its control over state institutions and will hold on to it by any means.

This includes conveniently distracting international attention from political repression with the current review of unlicensed “˜illegal sects’, which in the Angolan reading includes Islam. Historically, Islam has played a marginal role in the predominantly Christian (90%) country of Angola, with a small trading community of mainly Lebanese families as the only adherents. Since the end of the civil war in 2002, with the growing presence of West African economic migrants, several Mosques and Islamic schools have sprung up, and a small but noticeable number of Angolans have converted to Islam. However, although the authorities have tolerated the presence of these Mosques, Islam is still not recognised by the state as an established religion. The public and media discourse portrays Islam as “˜un-Angolan’, speaks of a “˜Muslim invasion’, and highlights the “˜dangers of Islam in Angola’: the Minister of Culture repeatedly declared she was “˜preoccupied’ with the expansion of Islam, while the Secretary-General of the Council of Christian Churches (CICA) named Islam as “˜one of the greatest challenges churches are facing at the moment’. In a context where the ruling party liberally uses accusations of “˜foreign interference’ to discredit any possible home-grown political dissent, Islam is equated with foreignness, illegal immigration, and terror risks (despite no factual evidence for the latter), and the current rumours about the alleged destruction of mosques serves the government’s purpose, though the Angolan ambassador to the US denied any government interference in religious affairs shortly afterwards.

Moreover, the attempted protests coincided with dos Santos’ second unscheduled recent stay in Barcelona, which raises mounting speculations about his alleged ill health. The regime’s overreaction indicates the risks inherent to an “˜uncontrolled transition’ in Angola, as dos Santos’ skilful nurturing of party-internal rivalries has made it impossible for a “˜natural successor’ to emerge: his appointed Vice-President Manuel Vicente has little backing among the party’s “˜Old Guard’, and while rumours abound that one of the President’s sons, José Filomeno “˜Zénú’ de Sousa dos Santos is being groomed for succession, this scenario is unlikely to placate popular discontent. Although Angola’s frustrated youth wish nothing more than an end to the “˜System dos Santos’, his prolonged absence or sudden incapacitation or death thus portents troubled times ahead for Angola.

Jon Schubert is a political risk analyst and a PhD Student at the Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh, where he is about to defend his thesis “˜Working the System: Amnesia, Affect and the Aesthetics of Power in the “New Angola”’, based on a year of ethnographic fieldwork in Luanda (Oct 2010-Oct 2011).

Twitter: @jon_schubert