Angola’s oil could actually be the DR Congo’s. Here’s why it isn’t.

About half of the oil being produced by Angola is in Congolese waters, according to the UN convention that defines maritime borders.

Angola is one of Africa’s largest oil-producers. Credit: East Hub Development Project

Angola’s politics lives off oil. The natural resource amounts for nearly 40% of GDP and 75% of government revenues. It has brought foreign investment and friends, and fed corrupt elites. Angola is one of the world’s largest oil producers.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), to Angola’s north, does not rely on oil. It only produces from some tiny fields off its diminutive coast and has yet to exploit potentially large reserves in the interior. The DRC is not oil-rich.

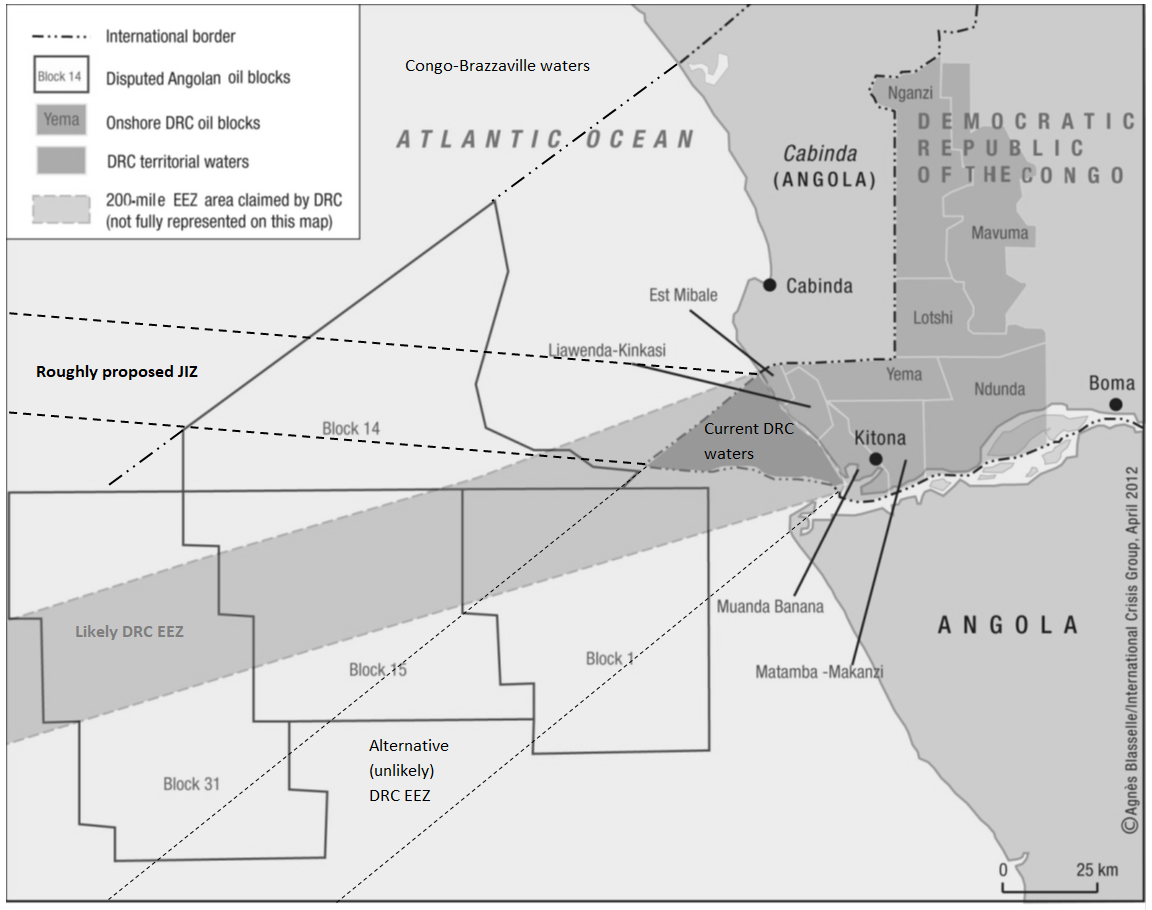

And yet, legally, the opposite could be true. Under the UN Convention that governs which strips of sea belong to which countries, the DRC could legitimately lay claim to enormous oil fields currently held by Angola. It could argue that reserves responsible for about half of Angola’s production are actually in Congolese waters and become one of Africa’s largest oil producers overnight.

So why hasn’t it? We explored this question in a recent paper. This is what we found:

Mobutu’s failed gamble

The story of the oil fields off Angola and the DRC’s coasts goes back to when offshore drilling first began in the 1970s. At the time, the waters were assumed to be Angolan but the importance of potential discoveries was not lost of President Mobutu Sese Seko of then Zaire who came up with a plan to win rights to the oil fields.

Firstly, he provided support to several armed groups who were fighting in the Angolan civil war such as UNITA, FNLA and FLEC. If they proved victorious, they would hand over Cabinda – an oil-rich exclave on the coast – and its waters to Zaire in return. He then doubled up on this strategy by instituting a law in 1974 that defined maritime borders in such a way as to ensure Cabinda’s waters would include its offshore reserves.

But the gamble failed completely. The armed groups Mobutu was backing were defeated. And to make matters worse, the method by which Zaire had decided to regulate its waters meant that – without being granted Cabinda – it was left with just a tiny triangle of maritime territory close to the coast. At the time, this was not too significant as it was not possible to drill far offshore. But from the mid-1980s, the technology improved significantly. Oil companies began drilling deeper into waters further and further out.

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), signed in 1982, provided Mobutu another chance. This law defined maritime borders as lines perpendicular to the coast in contrast to Mobutu’s 1974 law, which drew sea borders along the same trajectory as land borders. According to UNCLOS, the country’s waters extend 200 nautical miles into the Atlantic Ocean. But while Mobutu ratified the convention, he had neither the capacity nor the inclination to do anything about it. Zaire’s economy was collapsing and would soon descend into civil war.

Fear, dependence and cash

After his fall, Mobutu was succeeded as president by Laurent-Desiré Kabila (1997-2001) and then Joseph Kabila (2001-2019). Like their predecessor, neither father nor son was able to fully assert the DRC’s claims to the lucrative oil fields. The key reason for this was their reliance on, and fear of, Angola.

Angola is the DRC’s “most important” neighbour and its support was crucial to both the defeat of Mobutu in the First Congo War and the survival of the Kabilas in the Second Congo War. If Angola could make kings in the DRC, however, it could also unmake them. This fact strongly dissuaded the Kabila regimes from trying to claim Angola’s oil.

The two countries did discuss it, though, coming up with the Joint Interest Zone (JIZ) in 2004. Under this false compromise, Angola and the DRC agreed to share maritime rights and resources, but only over a fraction of the territory the latter could claim and in a less productive area. Under this proposal, Angola made no significant concessions, while the DRC gained little. The deal also undermined the DRC’s ability to make any larger claims.

This explains why the government in Kinshasa delayed signing it until after elections in 2007 when it desperately needed both money and Angolan support amid high government debt and low copper prices. In the words of a senior official involved in negotiating with Angola at the time, “the government was asking itself how to gain the necessary money to pay off international debt and how to develop the country economically. The possibility was raised of exploiting hydrocarbons. Thus emerged the JIZ.”

Our research also suggests Angolan officials used bribes to prevent the DRC making more assertive claims over the oil. According to one interviewee, they “put [Congolese officials] to sleep with money and other things so that the dossier never finishes”.

Money also sealed the deal through less secretive means. For example, the JIZ agreement also included the provision of oil rights to a company called Nessergy. This outfit, closely connected to friends of the Kabila regime, promptly sold on these rights for three hundred times the original price. More generally, the JIZ deal was closely controlled by President Kabila. Negotiations were led by the president’s inner circle rather than the relevant government institutions. Moreover, sources involved in the talks told us that the DRC’s representatives asked for payments from Angola to be paid in cash. Angola’s then president José Eduardo Dos Santos allegedly responded to this request by saying transfers should be made through banks, not “in sacks”

Keeping the dispute alive

Since then, the DRC has neither kept quiet about its rights to the oil nor fully asserted its claims. Instead, officials have maintained a pattern of noisy but ineffectual action, periodically raising the idea of joint exploitation or exclusive rights.

In 2009, a variety of Congolese government officials and parliamentarians even passed legislation regarding the DRC’s claims to the oil fields. President Kabila went along with these efforts for a while and signed a law that laid claim to the disputed zone. But the issue was then hushed up and the legislation sat unused. Many legislators we spoke to deny the law exists.

How to explain this contradictory behaviour? Again, it all ties to Angola’s backing of the regime. It seems that President Kabila calculated that while claiming the oilfields would scupper Angola’s support of him, keeping quiet would not necessarily ensure it. Another president could be just as compliant. Showing Angola what Congolese policy might be – for example if the regime were to lose the 2011 elections – may have been Kabila’s way of safeguarding Angola’s backing. He balanced applying pressure on his powerful neighbour while avoiding truly jeopardising relations.

For its part, Angola reaffirmed the risks the DRC would be opening itself up to if it did pursue its claims. In response to this and other disputes, it has expelled Congolese citizens from the country as its troops have started popping up in Congolese towns.

Will the DRC ever claim the oilfields?

Despite the fact it could become one of Africa’s largest oil-producers overnight, there is little chance the DRC will ever take control of its maritime territory as defined under international law or even reach a fair compromise. Its dependence on its neighbour makes the prospect of upsetting Angola too risky.

At the same time, the Angolan government will likely continue to offer cash – either individually in envelopes or through more official channels – to discourage any potential Congolese action on the matter. In recent years, Angola has reduced its security role in the DRC, especially under President João Lourenço. But as its hard-nosed policy against Cabindan separatists shows, Angola will continue to protect its core interests by any means necessary.

The current DRC government is simply not strong enough to take on its neighbour and, despite Felix Tshisekedi becoming president earlier this year, the DRC’s political landscape has not shifted radically. Kabila and his allies retain significant control and old dynamics remain. As President Tshisekedi courts Angola for support now too, he will be just as unwilling to anger his southern neighbours as his predecessors.

Hi there

Very shocked of the angolian’s oil fieldd. Realy shocked as african we are idiots

We like to please the west from far than our neighbour. Compensation will be with kainda situed far from angola. Why this happened? Greedy leader who killed albinos and praise white

I want to receive Africa news online.

To the three stooges (Dummy, Dumb & Dumber) who wrote this deceptive article in an attempt to deceive the public. Angola’s borders with Congo are the result of the Berlin conference of 1884 which preceded the U.N. It is there where you find the answers to why the current geographical map of Angola exists. This geographical region is true even during the colonial era and the reason why the Belgians don’t despute it. In summary; the portuguese would give the Congo access to the river congo ( Which means that half of the river would be congolese and the other half Angolan)… Therefore, it was Angola that lost territory in order to allow the Belgians to build the port in Matadi. The resources therefore of the Atlantic ocean and its maritime borders would be dictated by the portuguese authorities in benefit to Angola. The Congo (DRC) was actually a landlocked territory which manny people don’t realise, given to the Belgians under sole authority of the Belgian King with the signing of the Berlin Conference in response to the “British Ultimaton”. So Angola is absolutely correct and has legitimate legal authority over the Maritime waters in Kabinda region. Furthermore, Congo never supported FLEC. FLEC we’re nothing more than a bunch of adventurers supportes by the French government. And, there was never a deal for FNLA to hand over the territory of Cabinda to DRC. Mobutu, had plans to occupy Cabinda, but the angolan patriots in FNLA would never allow it.

You failed to mention that Angola occupies congolese EEZ(Exclusive Economic Zone).

Its not a maritime boundary dispute in the like of Kenya/Somalia or the recently settled Ghana/Cote d’ivoire one.

Congolese EEZ lies between Angola EEZ and Cabinda EEZ just like the Canadian pacific coast EEZ is between

Alaska EEZ and US EEZ or like Oman EEZ being separated from its Musandam EEZ by the EEZ of the UAE.

Angola has a maritime border with Namibia and DRC ;its Cabinda province has a maritime border with DRC and Congo-Brazzaville.

The Angola-DRC joint interest zone (JIZ) is a fraud. The only real JIZ Angola has is in the Cabinda-Congo-Brazzaville maritime boundary called Lianzi. I think the US-based Attorney Ed Patricoff was right of warning the UK not to let Angola join the Commonwealth until it ends its corrupt practices.

Je suis très ravis de pouvoir être chaque au courant de tous se qui se passe dans votre site.

That is a lie, the triangle is perfect calculated if you see angola sea border line in soyo, the line actualy goes up and not straight to the sea like you mention in the report… When you folow the lines from DRC North and south , they meet together forming a triangle.

If the line of south congo went straight it would hit soyo peninsula and invading Angola, sovereinty. It would be weird for us to be at soyo beach and not being allowed to bath in our waters full of congolese ships in a nice sunny whether. DRC only have access to sea thanks to Angolans who gave the access to the sea as a gift . Thats stril of land was ours abd connected to Angola, Cabinda Angola were never separated before berlin conference.

First drc begs to have a litle acess to the sea, second , they try to take Cabinda, third, they want our waters? Are doing this on behalf of your colonizers DRC.

I belive Angola should take back baskongo and reunite it again with Angola , as it should historicaly.

Drc better behave right and stop allow themselves to be a proxy of belgium and france, or else Angola will take 15% from drc if they invade Angola Again.

If you invade and lose the UN says, the invader loses 15%

This article doesn’t include any map and proof of claims, Angola does more for Congo than any other country has and even its own leaders. Angolan and Congolese people are the one family, and there will never be issues that cannot be resolved.

choloquine https://chloroquineorigin.com/# long term effects of plaquenil

cialis tablets cialis price