The Ben Ali Gap: Tunisia’s youth revolution turns over the reins of power to increasingly wrinkled hands – By Brian Klaas and Rafik Halouani

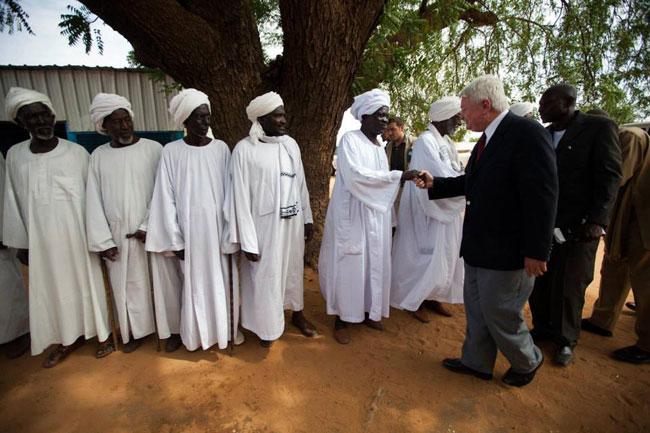

At 88, Ahmed Mestiri is one of a number of gerontocratic leaders gaining prominence in Tunisia’s post-Ben Ali public life.

Nearly three years ago twenty-six year old Mohamed Bouazizi had his vegetable cart confiscated by police. Bouazizi was denied an audience with local authorities when he sought to complain. Humiliated and frustrated by the dual scourges of political repression and limited economic opportunity, Bouazizi doused himself in gasoline and set himself on fire in protest.

This spark set Tunisia ablaze with political change that would eventually spread throughout the Arab world. With 90% of his body charred, the young vendor died on January 4, 2011. Ten days later, Ben Ali fled Tunisia. The 74 year-old dictator, accustomed to a life of opulence and luxury had been toppled by a conflagration ignited by a 26-year old struggling to support his family on an income of less than $5 per day.

Tunisia’s profound political change owes much of its momentum to young people. In addition to Bouazizi’s self-immolation, young Tunisians played a crucial role in forcing Ben Ali into exile and opening a new chapter of Tunisian history.

Yet, three years later, young Tunisians are not writing their national story. While the revolution may have been written with graffiti, on Facebook walls, and on Twitter in 140 characters, it seems that a quill and ink are being used today. After the fall of 74 year-old Ben Ali, ever more wrinkled hands are jockeying for the reins of power.

The reason for this is simple.

As Tunisia negotiates its transition, consensus and compromise are highly coveted by a political elite that is careful not to chart the same course as neighbouring Libya and Egypt. As a result, figures seen as polarizing””no matter how competent””cannot be considered for key positions.

Anyone who touched or came close to the reins of power under the Ben Ali regime is now considered politically toxic. This means that all top-level government officials, dating back to 1987 (when Ben Ali took power in a “medical coup”), are excluded from consideration as Tunisia searches for an interim Prime Minister to guide the country toward its perennially delayed elections.

This is the ‘Ben Ali Gap’, a phenomenon wherein an entire generation of political elites has been wiped off the political map””either in search of consensus and compromise, or as part of a 2011 “article 15 of the electoral law” law which sought to protect the gains of the initial uprising by ensuring that Ben Ali’s former allies could not be part of a new government.

As a result, the debate over who will lead a “˜technical’ interim government, constructed to prepare the country for elections, has stalled – torn between two old guard figures. The Islamist-led Troika and the opposition continue to bicker over two candidates””Ahmed Mestiri, an 88 year-old supported by the ruling Ennahdha party, and Mohammad Ennaceur, the opposition-backed 79 year old (a comparative spring chicken in this emerging gerontocracy).

Both candidates share a mutual affiliation with the (pre-Ben Ali) Bourguiba regime. Likewise, the leader of the most prominent opposition party (Beji Caid el Sebsi of Nidaa Tounes), who previously served as Prime Minister for ten months after Ben Ali fled, is about to celebrate his 87th birthday.

Whilst Tunisians in their twenties were a major driving force behind the revolution, the supposed “revolutionary regime” is turning towards people born in the “Roaring 1920s” to take power.

Tunisians, in the main, revere their elders, with grandparents often serving as heads of families late into life. Such traditions may be responsible for an emphasis on the value of wisdom gained through experience””and there is no shortage of experience for the ministerial relics of Bourguiba’s Tunisia. A result of Ben Ali’s repressive policy towards opposition movements, Ennahdha is led by people who spent their formative political years either in exile or in prison, but almost never in government. The same is true for those that were members of the previously suppressed democratic opposition parties under Ben Ali. They were never considered for high-level positions in the former regime.

As a result of these “˜gaps’ in political formation, Tunisians often malign a general lack of government experience as the revolution struggles on, limping forward with modest growth and growing security risks. Close to 50% of Tunisia’s population is younger than 30, yet only 4.6% of the National Constituent Assembly is younger than 30, and their vision for Tunisia may well be different from the vision of experienced political elites. The voices of Tunisia’s youth deserve to be heard.

This is not to say that young people have been completely shut out, or that the vast majority of elected officials are dinosaurs of a forgotten age. A select few elected officials are just 25 years old, and 40-50 year-olds are the most well represented age group in the elected assembly. Nonetheless, Tunisia’s political dialogue is undeniably gravitating toward elder statesmen rather than fresh faces.

This is a problem insofar as the underlying frustrations that caused Mohamed Bouazizi’s self immolation were political repression and a lack of economic opportunity. While it is clear that Tunisians enjoy significantly greater freedom than under the previous regime, young Tunisians continue to be largely excluded from political decision-making. Moreover, economic prospects remain grim, particularly with estimated youth unemployment stagnating above 30%.

In spite of these major challenges, there are hopeful signs on the horizon. While the elderly dominate the political realm a younger generation of young civil society activists projects a vision of a new Tunisia, at home and internationally.

For now, however, the old trees in Tunisia’s political forest are crowding out the sunlight needed for new growth. Nonetheless, activists speak of a day when the timbers that sprouted from the soil of Ben Ali and Bourguiba, may be uprooted. When that happens, it will be the realization of a true revolution, one that breaks with the past rather than clinging to an even more distant history.

Sadly, that vision has not been realized. It will not be anytime soon. Nearly three years have passed since a young man sparked a revolt that forced an elderly dictator to his knees, before fleeing to save himself. Today, the “˜Ben Ali Gap’ is doing the opposite, as Tunisians flock toward frail statesmen of a bygone era to save Tunisia.

Brian Klaas is a researcher of African politics at the University of Oxford. He is currently based in Tunis.

Rafik Halouani is a management consultant and activist in Tunisian civil society. He is the President of Mourakiboun, the primary network of domestic election observation in Tunisia.

Yesterday we reported on a group of young Muslim men who accost pedestrians in certain parts of east London. They insist that their turf is a “Muslim areaâ€, and require that non-Muslims observe the appropriate dress code and the Islamic proscription on alcohol while they are there. The original post included an embedded video taken by the group and posted on their YouTube account.