Rejecting the West on policy: Uganda, neoliberalism and the Anti-Homosexuality Bill – By Jí¶rg Wiegratz

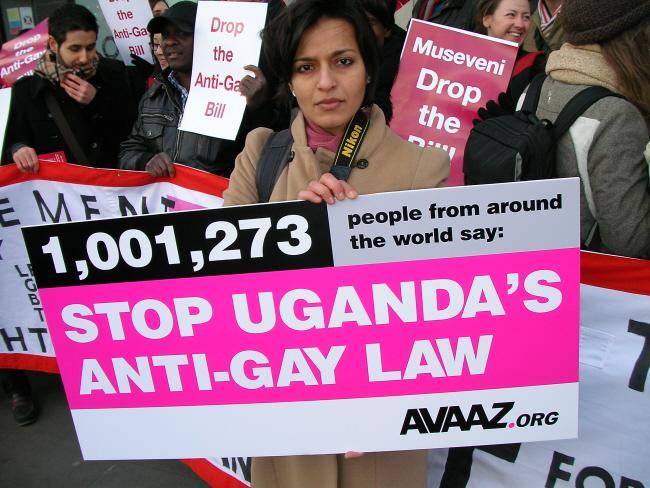

Much has already been written about the standoff between Uganda and the West on the recently passed Anti-Homosexuality Bill. For various analytical takes concerning the drivers, characteristics and repercussions of the bill see for instance here, here, here, and here. Given limited space, I will not directly engage with the points that were raised in these previous articles, including the analysis offered there regarding (a) the possible motives of the Ugandan government for signing the bill (quest for legitimacy, authority, sovereignty, election gains, religious enhancement, deflection, surveillance, etc.), (b) the political-economic dynamics that might have influenced the government’s course of actions (expected oil revenues, China as an alternative to the West, etc.), or (c) the role of different internal and external actors in shaping the bill-making process.

Instead, I will try to complement the analysis by focusing on three distinct features of the standoff. Before I lay them out it should be noted that the standoff is a complex political-economic and political-cultural phenomenon that deserves a more extensive analysis in future.

That said; let me first address three characteristics of the stand-off. First, it belongs to a very small category of cases during the era of neoliberalism where an African government has rejected a clearly expressed policy preference (No-Bill) that was widely shared and strongly supported by the Western Block of European and North American governments, aid organisations and NGOs.

It is hard to think of an equivalent case (perhaps leaving aside security politics) of such a clean-cut and significant standoff on a key policy matter in recent relations between “˜the West’ and African governments, where an African government has eventually walked away from the Western “˜consensus’. There are other cases that share that characteristic but they are all on a different, i.e. smaller scale; for instance, the use of state subsidies for fertiliser in Malawi (some in the Western block were against that).

Related to this is the fact that the standoff was about a “˜cultural’ issue. More specifically, the “˜anti-Western’ stand was taken by a key strategic ally of the West and long-standing “˜donor darling’, a country that has extensively adopted Western liberal policy recipes for more than 20 years. The crucial thing is that many of these adopted policies related to the realm of the economy and political economy: liberalisation, privatisation, “˜deregulation’, incentives for foreign investors and so on. The Ugandan government and by extension, the state, has generally not opposed the World Bank, IMF and major donor countries on this front – partly because various actors within or closely linked to the Ugandan state benefited from the policies.

The West furthermore demanded adjustments in line with liberal prescriptions in matters of polity and society too, and many of these demands were “˜granted’ as well. Substantial Western aid and assistance has flowed to the government in return for being a good partner. Of course, there was criticism for years from sections of Uganda’s political class and people about the purpose, level, and form of influence from actors such as the World Bank, IMF, EU, the US or various Western European governments in the country’s affairs (the same is true in other African countries). The point is that despite the criticism of the West’s economic policy dictats (and of Western societal engineering in the country more generally) the government never fundamentally opposed them.

Instead, it now defied “˜Big Brother’ and opted for policy unorthodoxy on a seemingly “˜cultural’ issue, i.e. specific norms, values, and practices. There may well be a link between compliance with the West’s reform pressure for more than two decades, and rejecting it now (a decision that was respected by, for instance, the South African government). In other words, a significant standoff of one sort or another was coming for a long time, in Uganda or any other African country that has been shaped by foreign intervention in the neoliberal era of donors.

It is also not particularly surprising that it was Uganda that made such a public break with this key pillar of the Western Block’s liberalism (free markets, individual freedom and human rights.) The country has been the ground for foreign-induced neoliberal experiments at an unprecedented level in terms of foreign financial back-up, staff, ideology, and governance technology to carry out a liberal recalibration of Ugandan society towards a prototype market society. This foreign intervention was always also a form of cultural engineering, even if the official target was economic, legal or political reform.

Significantly, anti-homosexuality dynamics are evident in other African countries as well, and some of these countries have undergone a foreign-induced neoliberalisation too. Similar dynamics can be observed to various degrees in countries elsewhere, including the US, Germany, Russia, and various key allies of the West.

The third characteristic is that the sections of the Ugandan government and state as well as the politicians, organisations and people in the country that officially supported the bill, and by extension confrontation with the West, accepted the (threat of) punishment for non-conformity. Supporters of the bill knew that the move is likely to be very costly in financial terms.

Normally, the threat of sanctions including aid withdrawal and the incentive of continued and increased aid flows have ensured that the West pretty much gets its preferred policies in neoliberal Africa and that the IMF and World Bank have never had to face a serious policy defeat of late. I will neither analyse the factors that might have brought about a different outcome in this case; nor the ongoing negotiations regarding aid cuts. Rather, I conclude that more research is needed to unveil the dynamics that shaped the three features that I have highlighted above: (i) opposing the West on a key policy point, (ii) about a non-economic matter, (iii) in the face of severe sanction threats.

Dr Jí¶rg Wiegratz is lecturer in Political Economy of Global Development, University of Leeds, School of Politics and International Studies, [email protected] http://www.polis.leeds.ac.uk/about/staff/wiegratz.php

I perceive the article to be a cleverly written piece intended to provoke further debate.

The issue is indeed complex. Africa’s social engineering is basically grounded on age and gender specific roles. There are very few “gray areas” when it comes to the roles played by gender and age related duties. Thousands of African cultural practices outline what children are supposed to say to adults (not just anyone as is the case in the West) and vice versa. The West, on the other hand, appears to be more interested in what adults say to children and less concerned about what happens in the opposite direction.

In short, the dangers of establishing equally vile institutions (by comparison to the homosexual law) such as same-sex marriage is more noticeable to an African government than a western one. The failing concept of gender constructionism is ebbing away the fabric of western society but they seem oblivious of it. This is not surprising as it is characteristic of western societies to continue a dangerous idea until it becomes too costly to turn back; then they turn! Slavery and racism are just two of such.

I do not personally support Uganda’s harsh treatment of homosexuals but I support their rejection of neo-liberal ideals from the west which will destroy any society when adopted.

Many do not realise that it takes generations for evil human laws to manifest.

The West should remove the log in their eye before they can see the speck in the Africans’