Ethiopia’s national dialogue commission: where are the women?

Men dominate the commission for reconciliation talks. A lack of inclusivity risks undermining the initiative, but it is not too late to correct it.

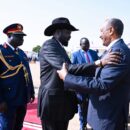

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (in light blue) of Ethiopia on a state visit to Rwanda in 2018. Credit: Paul Kagame.

In December 2021, Ethiopian lawmakers voted to establish a National Dialogue Commission to oversee “broad-based inclusive public dialogue that engenders national consensus”.

Not long after, a coalition of Ethiopian women’s organisations issued a joint statement calling for the meaningful representation of women in the new body. Yet when the lawmakers narrowed the pool of 632 potential commission members, who were nominated by the public, to 42, only 4 women remained. The final list of 11 commissioners includes 3 women.

The prospect of a male-dominated commission when there is no shortage of competent women indicates major flaws in the selection process. This should be addressed before the commission proceeds with its work.

Ethiopian women’s groups advocated early on for a gender quota to be included in the law establishing the commission. When this failed, they called for the selection process to nevertheless ensure equal representation, for women’s organisations to be represented in the nomination process, and to have the opportunity to participate in the screening process. None of this happened either.

Generally, there was a lack of transparency and clarity in the selection criteria: how it would be applied, how civil society would participate, and how the process would be managed. No one seems to know how parliament got from 632 to 42 candidates, or from 42 to 11. The selection process was not participatory, inclusive, or transparent.

The purpose of the National Dialogue is to alleviate the differences and misunderstandings between various political and ideological leaders and sections of society in Ethiopia. It would make sense, therefore, that as much as possible, the National Dialogue commissioners should represent the diversity of Ethiopia – including women.

What parliament can still do

Even though 11 commissioners have been selected, parliament could still retrace its steps. It could amend the law establishing the National Dialogue and re-open nominations for additional commissioners. It could limit the call for new nominations to women only to ensure it has a pool of candidates to correct the gender imbalance.

It could also take steps to increase public awareness about the commissioners selected and any additional ones to support public buy-in. It could, for example, clarify selection criteria, publish the rationale for selection, or televise interviews with selected members. Such steps would help Ethiopians feel more involved in the process.

Going forward, the commissioners should ensure they consider all elements of inclusivity in selecting experts, committee members, and other staff of the commission. They should hold consultations with the public, particularly women’s groups and others who feel underrepresented, to develop a shared vision for the commission’s overall composition, with inclusivity at the heart of it. What are public expectations for the participation of women, youth, ethnicities, people living with disabilities, diaspora and civil society? This vision should have the goal of ensuring the levels of diversity the commission needs to be acceptable to a large number of Ethiopians.

Undoubtedly, the more representative the commission is, the greater the participation of all people, the more productive it will be.

Inclusivity at large

Since Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed shared the government’s plans to establish the commission in July 2021, the question of its inclusivity has been hotly debated.

The debate has focused primarily on the extent to which the composition of the commission and the process towards its establishment will include political opposition groups, including those in active hostilities with the federal government. Some argue that the commission should proceed, with the possibility that opposition groups may join the process at some point in the future. Others propose a sequenced approach, in which a peace process (or at least a ceasefire) is attained to enable the participation of all Ethiopia’s political groups.

Women’s representation – and that of other groups – however, is not a dimension of inclusivity that has inspired much debate. In contrast, when Abiy became Prime Minister, inclusivity was apparently front of mind as he formed a cabinet that was half female. At continental and global levels, the Maputo Protocol and UN Security Council Resolution 1325 protect and support women’s right to equal participation in political life and in peace and security processes – and history shows these processes have a higher likelihood of working when women are included.

While parliament may feel political pressure from various local and international stakeholders to ensure the commission starts its work, they should slow down and conduct a thorough reflection on how and why inclusion is not being achieved in a process to address critical issues and build national consensus.

Without this, structural inequalities and societal tendencies that exclude women, minorities, people living with disabilities and other marginalised groups are likely to result in a commission that is unable to achieve the objectives of the National Dialogue.

Women suffer the negative consequences of the absence of national consensus. Their voices and leadership should contribute equally to addressing the root causes of crises in Ethiopia.

Why are you using this picture of PM Abiy with General Paul Kagame? Is this is to imply that Ethiopia will undertake a reconciliation process like Rwanda’s? If he does, then I don’t have any hope for it. Rwandans are not reconciled and even the CIA country reports say that it’s like a powder keg that could explode any time. I can’t keep track of all the people Kagame has had assassinated both inside and outside Rwanda.