Banda and the new broom: the trials and tribulations of a Zambian spin-doctor – By Magnus Taylor

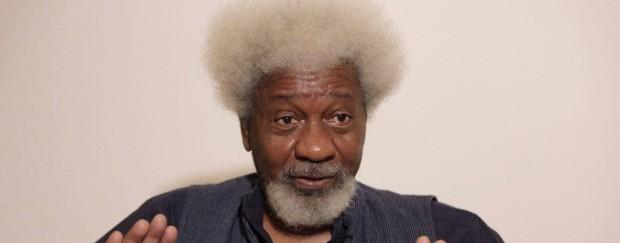

Rupiah Banda: an affable Zambian ‘political dinosaur’ and subject of Dickson Jere’s new book: ‘Inside the Presidency.’

I came across Dickson Jere at a lunch I got a late invite to as a replacement for a much better-known journalist. Still, beggars can’t be choosers, and I sat next to a man who introduced himself as having “˜floated Zambeef.’ We’ve also been stepping up our Zambia coverage of late as the country is often neglected in favour of its more turbulent neighbours, Zimbabwe and the DRC.

Jere is a larger than life fixture in Zambian political, journalistic and legal life. He has also clearly turned himself into a bit of a “˜fixer’ for international investors, knowing as he does “˜how things work’ in Lusaka. This is probably why he was being hosted at a swanky Soho eatery by a risk intelligence company and singing for his supper with an (of-the-record) political briefing.

Jere started out as a journalist, working for such titles as Africa Confidential and the more mainstream AFP. He left the profession in the late noughties to join the presidential campaign of Rupiah Banda, a self-described Zambian “˜political dinosaur’ and Vice President to Levy Mwanawasa who, in 2008, unexpectedly died whilst at an African Union summit in Egypt. Banda decided to run for president in the snap election that followed.

Jere was brought on to the campaign to run the press operation, and then subsequently kept on in State House as “˜Chief Analyst for the Press and Public Relations.’ He has now written a book recounting his experiences during these 3 years working for Banda enticingly titled: “˜Inside the Presidency: trials and tribulations of a Zambian spin-doctor.’

The title is, however, a clue to the book’s approach: this is the work of a loyal political operative, so its largely positive assessment of the Banda presidency should be taken with a pinch of salt. I am not a Zambian political insider, and would defer to Jere on such matters, but a quick bit of cross-checking with the author’s former employers at Africa Confidential confirmed my suspicions that he may have “˜sanded the edges’ of some of the controversies and inevitable failures of Banda’s short period in power.

But this doesn’t detract too much from many of the insights the affable Jere provides into the day-to-day running of the administration, and particularly his attempt to modernise State House’s PR and communications operation.

The way in which the author comes up against the stifling bureaucracy of the institution, which seems to be run almost entirely by members of the security services, is somewhat comical. But this also provides Jere with the opportunity to portray the Banda administration as the progressive “˜new broom’ ready to sweep away the old “˜system’ of entrenched self-interest and inefficiency.

Ironically, given Jere’s account of his own modernising programme, it was President Banda’s association with the “˜old’ regime – that of the MMD party of Chiluba and Mwanawasa – in power for over 20 years after dethroning Kenneth Kaunda in 1991, that was the main reason he lost the 2011 election to Michael Sata’s Patriotic Front.

The PF gained the support of the majority of first time voters who were attracted by Sata’s simple campaign on jobs and “˜more money in your pocket.’ Sata also channelled a growing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country by suggesting that he would be much tougher on the new economic migrants than the more reticent Banda.

As president, Banda presided over strong growth in the country’s copper economy, benefitting from the continent-wide commodities boom, and used government revenue to finance a slew of infrastructure projects, but he was also considered to be somewhat weak on corruption. Accusations in this regard came both from his political opponents and international NGOs operating in Zambia, such as Transparency International.

Jere himself is open about why Banda didn’t win a second term, admitting that Sata had a stronger campaign message and more entrenched political profile, particularly for younger voters. Africa Confidential (“˜How Banda Got Bounced’) in October 2011 also commented that the Banda campaign was poorly run:

“Campaign headquarters…was packed with people with no clue what the densely packed townships wanted.”

The publication does however reserve some praise for its former correspondent: “Banda’s eldest son…and press and public relations assistant Dickson Jere, operated outside of headquarters, backed mainly by non-MMD members, young people and musicians.”

The book is full of many enjoyable anecdotes about life working in Zambia’s State House. One of these is an account of a discussion the President had with his team on press freedom. After The Post newspaper published a corruption allegation against Banda, one of his “un-appointed advisors” recommended that they “just ban the Post newspaper.” Jere, however, wonders whether that “could… be the answer to negative publicity? I didn’t agree with that reasoning especially since newspaper banning had been tried elsewhere in Africa without success.”

The Zambian population, not unlike the current UK electorate, seems to assume that all politicians (with some justification) are simply in it “˜for themselves,’ so even the most foundation-less accusation can ruin a career. The fact that Banda pronounced himself “˜relieved’ when former President Chiluba was acquitted of corruption charges, when most of the country assumed him guilty, can’t (despite Jere’s clearly positive influence) have helped to dissuade the population that he wasn’t a product of the same old “˜system’.

Magnus Taylor is Editor of African Arguments.