Boko Haram’s Gwoza ‘caliphate’ demonstrates group’s increasing power – By Omar Mahmood

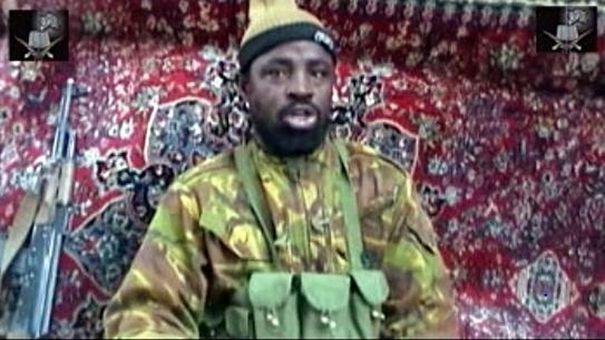

On 24th August a video surfaced featuring the Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau boasting about his organization’s exploits in northeast Nigeria. Shekau went on to state that the town of Gwoza, an area with a Christian population, is now under Boko Haram control and ruled by “˜Islamic law.’ The statement was surprising in that, until recently, Boko Haram has made little attempt to hold territory during the course of its five year struggle, and Shekau’s words echoed the Islamic State’s declaration of a caliphate under Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in late June.

However, while Shekau’s video likely falls short of the establishment of a caliphate in the ever expanding areas of northern Nigeria under the organization’s sway, it does suggest a significant evolution in Boko Haram’s strategy, with severe consequences for the Lake Chad region.

Despite being widely reported, an analysis from the Long War Journal concluded that Shekau likely did not declare a caliphate, while other outlets have been careful to translate his statement on Gwoza as an area that is now “˜Muslim territory’ under Islamic law. Such interpretations fall in line with the fact that Shekau mentioned an Islamic state or law only twice during his 23-minute speech. Rather, the majority of the statement dealt with common themes revolving around threatening youth vigilante groups collectively referred to as the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), criticizing democracy, and countering the Nigerian Army’s narrative on recent events, in the northeastern town of Damboa.

In this sense, the somewhat confusing nature of Shekau’s words regarding Islamic rule and law, suggests that an official caliphate declaration was likely not the message’s intention, with the video rather serving as part of a pattern of somewhat steady updates on Boko Haram’s progress.

In addition, it is highly unlikely that Shekau was declaring allegiance to the Islamic State (IS). In a July 2014 video, Shekau referenced “˜Al Baghdad,’ his first explicit comments related to IS. However, Shekau mentioned Al-Baghdad amidst a host of other jihadist leaders (including Mullah Omar and Sheikh Al-Zawahiri), and made no mention of the split between IS and al Qaeda, the latter ofwhich Boko Haram has claimed support from in the past.

In this sense, Shekau was likely seeking to bolster his jihadist credentials by sending greetings to other similar international figures or organizations, a practice not uncommon in recent statements, rather than specifically aligning himself with the Islamic State.

The Lead up to Territorial Control

Even if a caliphate declaration was not the intent of Shekau’s message, his assertions regarding territorial control of Gwoza are something new. One of Boko Haram’s goals has been to replace the Nigerian Government, democracy, and constitution with an administration ruled by sharia law. While objectives have evolved over time, messaging regarding this point has been consistent over the past few years.

Nonetheless, the movement demonstrated little appetite to undertake such a venture until recently. In July 2014, the organization moved on Damboa, though despite Shekau’s claims to the contrary, has been pushed from there since. Boko Haram has, however, in past few weeks undertaken an astonishing territorial push, reportedly occupying Buni Yadi and Bara in Yobe state, Madagali in Adamawa state, and Gwoza, Banki, Gamboru-Ngala, Ashigashiya, and Kerawa in Borno state among other locations, some of which lie directly on the border with Cameroon.

While occurring at a rapid pace, the groundwork behind this advance may have been in the works during in the past few months. In a video message in May of this year, Shekau discussed Usman dan Fodio, praising the Fulani historical figure who led an uprising that resulted in the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate in the 19th century. Despite clashing with the descendants of this empire, Shekau and Boko Haram likely draw inspiration from this example, and a Boko Haram spokesman previously called for its restoration.

Additionally, in July, suspected Boko Haram fighters blew up bridges in Yobe, Borno, and Adamawa, all states currently under a state of emergency (SOE) in Nigeria. The new-found emphasis on transport infrastructure, combined with Boko Haram’s already established prowess on major routes in Borno state, may have been designed to isolate certain areas primed for takeover, and slow down the flow of reinforcements from Nigerian security forces.

Furthermore, a wave of public discontent has spread within the Nigerian army units battling Boko Haram recently, perhaps allowing for conditions ripe enough to initiate a phase of territorial control. Consistent complaints have emerged from soldiers regarding a lack of equipment and corruption amongst senior leaders, to the point where some have even refused to fight. The recent flight of over 400 hundred Nigerian soldiers into neighboring Cameroon after a confrontation with Boko Haram militants is a prime example of the serious state of disarray the army finds itself in and the battlefield advantage Boko Haram currently fields, allowing for continued territorial advances.

Moving Forward

Similar to IS, Boko Haram’s territorial grabs over the past few weeks have been swift and met by a lower than anticipated level of resistance. The gains have led to pockets of territory in northeast Nigeria where government writ currently does not apply, which some believe are strategically located to encircle the Borno state capital and former Boko Haram stronghold of Maiduguri, perhaps signaling the militants’ next step.

Furthermore, indications have emerged that Boko Haram is doing more than just holding territory, but also attempting to implement governance, reportedly appointing a new Emir in Gwoza, executing a drug dealer and others for smoking cigarettes in Buni Yadi, instructing residents to defy government-imposed curfews in Madagali, and openly preaching in Yobe state.

Conflicting reports have emerged whereby some residents stated Boko Haram fighters explicitly informed locals they are not there to kill them, beyond some select individuals, in stark contrast to the past year of intense civilian targeting. Nonetheless, civilian abuse has been reported in places like Gamboru, including claimed executions of Christians, while militants have also gone door-to-door in search of fresh, and ostensibly forced, recruits.

Boko Haram is a fluid movement with continually evolving tactics, and the capture of territory is the latest step in this process. Prior to a state of emergency in May 2013 and the public emergence of the CJTF, Boko Haram was largely an urban phenomenon, with its stronghold in some of the wards of Maiduguri. The exodus from the cities turned Boko Haram into a rural organization with devastating consequences for villages in Borno state, but also demonstrated the organization’s agility.

This evolution has been seen in other arenas, from an initial refusal to engage in kidnapping, to conducting high profile kidnapping for ransom operations targeting foreigners across the border in Cameroon, to the mass abduction of over 200 schoolgirls, in addition to countless other local citizens. Many other examples speak to Boko Haram’s adaptability – the only constant is that the movement will change, and typically in an increasingly violent fashion.

Thus, while Boko Haram may not have evolved to the point whereby it has declared a caliphate or allied with an emerging one, the seizure and holding of territory along the lines of the capture of northern Malian towns by al Qaeda-linked militants in 2012 or even al-Shabaab in Somalia, is now part of Boko Haram’s operational strategy.

Likeminded jihadist militants in those areas overwhelmed local actors and instituted governance over a wide range of territory and people, until outside forces intervened (and continue to do so). While it is unclear what Boko Haram’s next steps may be and if similar measures will be required to reverse its progress, Nigeria and its neighbors have called for greater international support to help hinder its growth.

Boko Haram is in a continual state of transition, and seemingly always a step ahead of the Nigerian security forces. This is perhaps the most sobering element, the fact that after 15 months of emergency rule in Nigeria’s northeast, Boko Haram appears to be at a stronger point than ever before – with its newfound capacity to hold territory serving as an indictment of the failures experienced by the Nigerian Government, and a foreboding sign for the region.

Omar Mahmood is an Africa security analyst primarily focused on Boko Haram.